Why CGI Humans Are Creepy, and What Scientists Are Doing about It

A century ago, psychologists identified "the uncanny" as an experience that seems familiar yet foreign at the same time, causing some sort of brain confusion and, ultimately, a feeling of fear or repulsion. Originally no more than a scientific curiosity, this psychological effect has gradually emerged as a profound problem in the fields of robotics and computer animation.

The most familiar things in the world to us — the voices, appearances and behavior of humans — are being replicated with increasing veracity by animators and robotics engineers. Today's ultra-lifelike androids and computer-rendered humans would seem to bridge the valley between the land of the living and the distant cartoon world occupied by Disney princesses and animé characters. But these characters aren't so much bridging the valley as falling into it. When we look at them, they seem at once familiar and eerily alien, triggering an uneasy feeling.

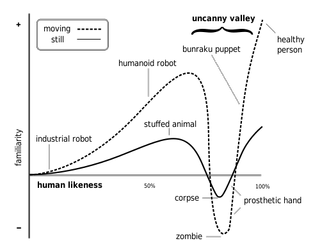

The spooky region occupied by these characters, so close to us and yet so far, is known as "the uncanny valley." The term comes from a graph created by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori that plots human empathy against the anthropomorphism of robots. On the graph, as robots become more realistic and we feel more and more empathy for them, the line trends upward. But as the robots' humanism approaches that of actual humans, our empathy for them — and the line on the graph — suddenly plummets. The resemblance between human and robot goes from remarkable to repulsive, and this precipitous drop became known as the "uncanny valley."

Karl MacDorman, a professor in the Computer-Human Interaction Program at Indiana University, leads a research team that is investigating why, psychologically, the uncanny valley exists. He hopes his research will help animators and other roboticists bridge the valley by creating human replicas that come across as lifelike and natural rather than creepy. Doing so won't just improve animated movies and video games; androids are becoming more widely used in everything from the service industry to iPhone apps to scientific research. They're here to stay, so scientists are doing what they can to make their presence more pleasant.

Mapping out the valley

Since 1970, when Mori first described the uncanny valley effect in the context of robot/human interactions, scientists have been trying to determine what it is about humanlike non-humans that creeps us out, exactly.

According to MacDorman, occupants of the uncanny valley have one defining quality: "an eerie feeling elicited by a human character that is highly realistic in some aspects but not others," he told Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. For example, as MacDorman discovered in a recent study, "this feeling can be elicited by a mechanical-looking robot that sounds human or a human looking robot that sounds mechanical — or moves in a mechanical way." [How the Cleverbot Avatar Talks Like a Human]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In other experiments, MacDorman's team showed that people feel particularly disconcerted when characters have extremely realistic-looking skin mixed with other traits that are not realistic, such as cartoon eyes. Furthermore, in a 2009 study in which participants were asked to choose the eeriest-looking human face from among a selection, the researchers found that computer-rendered human faces with normal proportions but little detail were rated eeriest. When the faces were extremely detailed, study participants were repulsed by those that were highly disproportionate, with displaced eyes and ears. In short, viewers seemed to want cartoonish facial proportions to match cartoon-level detail, and realistic proportions to match realistic detail. Mismatches are what seemed eerie.

Based on his research, MacDorman thinks the uncanny valley effect happens when certain realistic traits lead us to expect all other traits to be realistic as well; we feel disturbed and repulsed when our expectations are then violated. Strangely, though, only human characters can trigger the effect. In the highly successful computer-animated film "Avatar," for example, "the uncanny valley was avoided by reserving computer rendering primarily for the Na'vi characters and not the human characters," MacDorman said. The alien Na'vi in the 2010 film were humanoid and extremely lifelike, but they were blue-skinned with other clearly non-human features, so they didn't trigger the uncanny valley effect. [Inside Movie Animation: Simulating 128 Billion Elements]

Creepy feeling

So why do we feel unnerved or repulsed by quasi-humans, but not quasi-dogs or computer-rendered Na'vi? What's the evolutionary root of this psychological phenomenon? There are several hypotheses, but as yet, no scientific consensus. One is that the actions of androids and computer-rendered humans might deviate subtly from how we expect humans to socialize and interact, and as acutely social beings, we find the violations of our social norms disturbing.

Alternatively, psychologist Christopher Ramey of the University of Kansas suggests we struggle with the conceptual strangeness presented by androids. "Humanlike robots may force one to confront one's own being by creating intermediate conceptualizations that are neither human nor robot," Ramey wrote in a 2005 article.

A third hypothesis is that "uncanny valley" characters differ subtly from what we perceive as healthy and beautiful, and that we reject them just as we reject mating with those we perceive to be reproductively unfit. Along similar lines, other theorists have argued that we feel disgusted by uncanny valley characters for the same, evolutionary reason that we feel disgusted by certain diseases. We sense that they are somehow diseased, and steer clear in order to avoid contagion.

No one knows which of these guesses is correct. "I am working on testing the various theories," MacDorman said.

Billion-dollar issue

Whatever the psychological root of the problem, there's a lot to be gained from figuring out how to get around it. Many computer animation studios, including industry leader Pixar, shy away from characters that might get lost in the uncanny valley, preferring cartoon stylization instead. They've watched braver studios fail. For example, ImageMovers Digital, a computer animation firm headed by producer Robert Zemeckis, produced a series of critical and commercial flops because of negative audience reactions to their eerie characters.

MacDorman says it's easy to see why many of Zemeckis' CGI (computer-generated imagery) films flopped — starting with "The Polar Express" in 2004 and including "Beowulf," "A Christmas Carol" and "Mars Needs Moms." "A common feature of Zemeckis' films is a mismatch between the characters' physical appearance and movement owing to the misuse of motion capture technology," MacDorman said. (With motion capture, human actors are filmed and their motions are used to animate digital characters.) "For example, in 'A Christmas Carol,' we see an old man thrust into the heavens, and yet his movements are that of a young acrobat. This mismatch between appearance and behavior breaks the illusion of being transported into another world. Audiences lose their identification with and empathy for the characters."

Ward Jenkins, an animator and blogger, has pointed out that characters' eyes are often overly bright compared to the shadowy lighting of scenes in Zemeckis' films, and that their eye/skin mismatch lands them in the uncanny valley.

As Zemeckis has no doubt become acutely aware, you can't make much money on a film whose uncanny protagonist doesn't garner empathy from the audience. ImageMovers Digital closed in March after the failure of "Mars Need Moms," though it announced in August that it would reopen and continue trying to perfect the use of motion capture.

MacDorman says success will require matching the level of realism of all aspects of the characters.

After all, according to MacDorman, there is much to be gained from bridging the gap between the cartoon and the real world. "Clearly, many topics demand a high degree of realism, of authenticity," he said. "However, sometimes they also demand the impossible of actors, such as extreme age progression and regression in 'The Curious Case of Benjamin Button' or aerial acrobatics in 'The Matrix.'" [See video]

Those two films used computer animation in a way that did not produce disturbing results, MacDorman said. This was partly because CGI was used only when necessary, to animate actions that human actors could not perform, and within this limited scope, great care was taken to give all aspects of the characters the same level of realism. "Many viewers did not realize that in 'The Matrix,' digital doubles of Keanu Reeves and Hugo Weaving were used in some of the scenes," he said. "'The Curious Case of Benjamin Button' was particularly adept at modeling and animating an elderly digital double of Brad Pitt and compositing into actual film footage. This is a case where we can say that the uncanny valley was bridged."

This article was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to SPACE. Follow us on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.

Most Popular