A History of Mystery Blobs, Oozes and Goos in the News

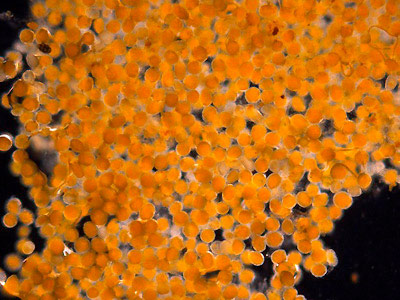

Bizarre orange goo that alarmed and baffled a remote Alaskan village for several days has been identified as a carpet of millions of invertebrate eggs. It was non-alien and non-toxic; the curious orange color resulted from fatty oil seen through the transparent egg sacs.

Though the orange goo had never before been seen in the area, it is only the latest in a long history of reports of strange slimes, blobs and goos. [Great Kraken: Why Scientists Should Study Sea Monsters]

While the egg blobs inside the Alaskan goo were too small to be accurately identified by sight, sometimes blobs have been too large to be correctly identified. Take, for example, the huge, smelly, whitish masses of obviously organic flesh rarely found on beaches around the world. (America's most famous "blobster" washed ashore at St. Augustine, Fla., in 1896.) Often mistaken for sea monster carcasses, they were eventually identified as decomposing great whales.

[Alien Coffee Mug: Get Yours in the SPACE.com store]

Last year a bizarre, 4-foot (1.2 meters) brown-and-yellow blob discovered in a lake in Newport News, Va., caused a commotion and made national news. Some thought it was a monster; others suspected an alien, or even a movie prop. In a twist reminiscent of the Alaskan goo, the mysterious aquatic blob turned out to be a bryozoan, a colony of tiny creatures that eat algae. Why it suddenly appeared in the lake was anyone's guess, though scientists suggested a passing bird might have introduced it.

It's perfectly understandable that people would be initially baffled by such strange phenomena, especially before the development of modern science and forensic analyses. With today's quality microscopes and sophisticated DNA techniques, just about anything new or (temporarily) unexplained can be identified, from chupacabra carcasses to strange slime.

Not so only a century or two ago: Volcanoes erupted, spewing ash high into the atmosphere and depositing a rain of "mysterious" white or light-gray wisps hundreds or thousands of miles away on people with no knowledge of the eruption. These days, of course, the whole world would know about it within minutes; science and technology have made the world a much smaller place and helped solve (or prevent) mysteries.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Charles Fort, a collector of reports of strange phenomenon, described in his 1923 book "New Lands" (Cosimo Classics, 2004) a report in the late 1880s of weird goo that was not orange but pink: "half a mile from Lilleshall, Shropshire, [England], an unknown pink substance was brought down by a storm." Sadly he provided no further details on this curious incident, but he reported on another account from late May 1889 of "an unknown substance that for several hours had fallen from the sky — crystalline particles, some pink, and some white" onto the island of Hyeres, in the Mediterranean off the coast of France.

In another account, Fort wrote, "In Wilna, Lithuania, April 4, 1846, in a rainstorm, fell nut-sized masses of a substance that is described as both resinous and gelatinous. It was grayish and odorless until burned; then it spread a very pronounced sweetish odor. It is described as like gelatine, but much firmer... in 1841 and 1846, a similar substance had fallen on Asia Minor." Nut-sized blobs of strange grayish jelly? Gross.

What were these (and other) strange slimes, oozes and blobs discovered throughout history? A century or more after the fact there's no way to know, but the most likely explanation is that — like the Alaskan orange egg goo — they were perfectly natural (though unusual or misunderstood) phenomena.

Benjamin Radford is deputy editor of Skeptical Inquirer science magazine and author of Scientific Paranormal Investigation: How to Solve Unexplained Mysteries. His Web site is www.BenjaminRadford.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus