Scientists Built a Virtual Reality 'Holodeck' for Lab Animals

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Devotees of the late, great sci-fi series Star Trek: The Next Generation will remember the holodeck, a space-age virtual reality arena that could replicate any kind of environment. While it could be used as a training platform, Enterprise officers most often used the holodeck as a recreational space, immersing themselves in nature.

In an inspired twist on the concept, researchers in Europe have developed a virtual reality environment for freely moving animals that appears to be effective at generating convincing illusions of the natural world for mice, fish, and fruit flies.

Alas for the animals, the VR system isn't designed for the animals' recreational benefit. Instead, researchers hope to use the VR rig as a controlled setting for examining animal perceptions and behavior.

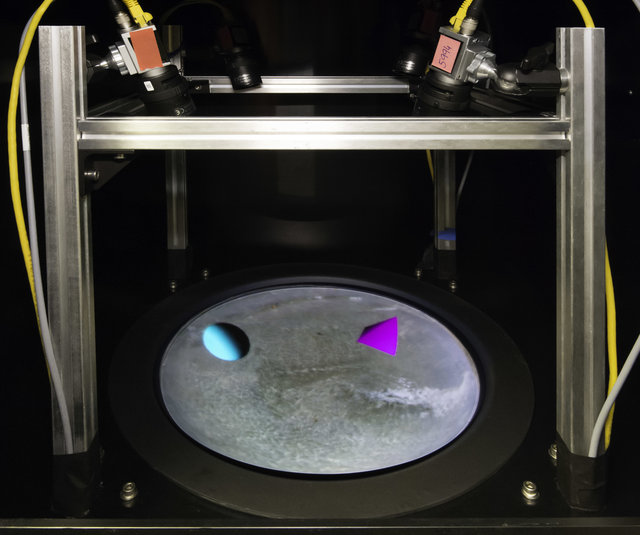

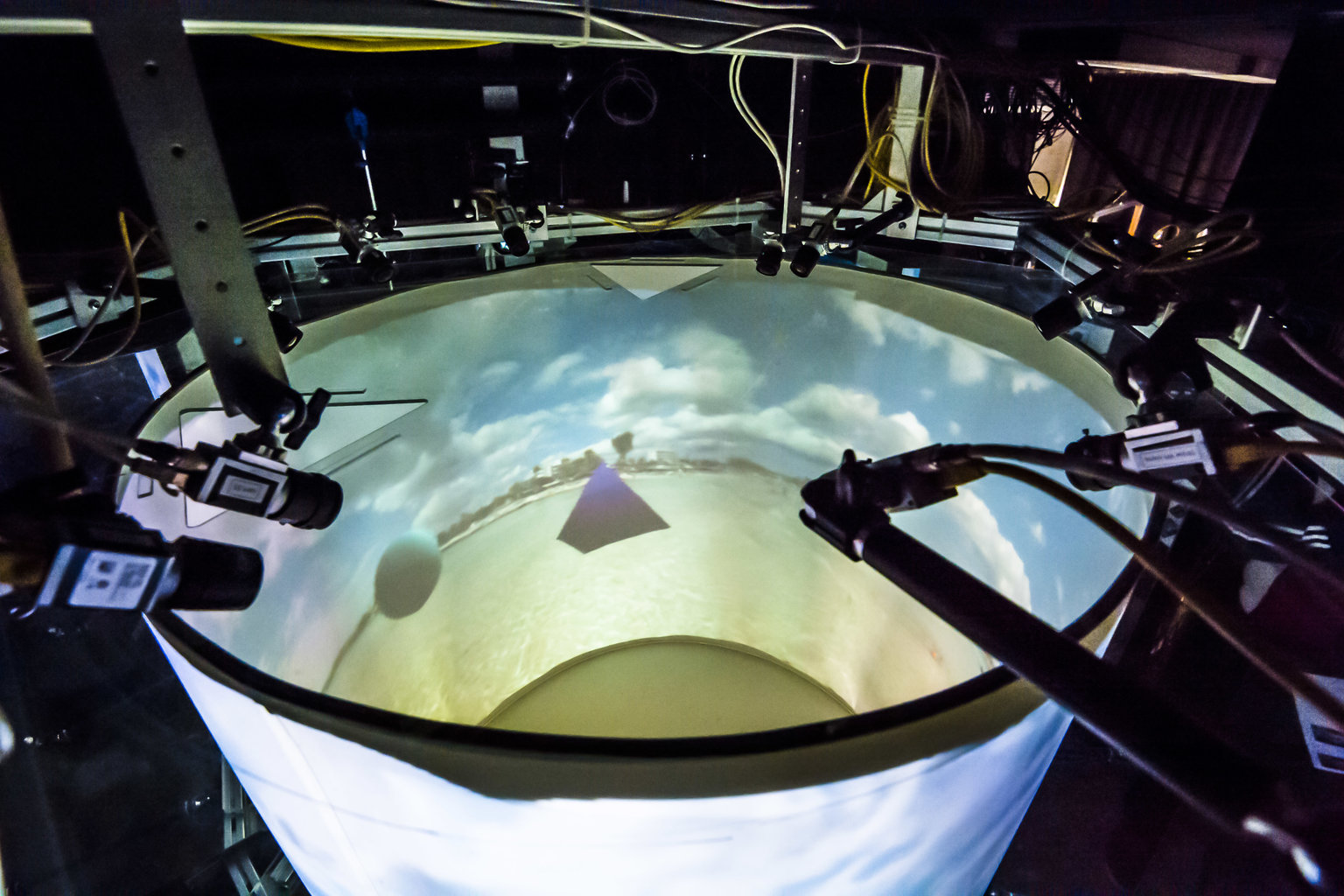

Dubbed FreemoVR, the system is actually pretty basic as far as virtual reality environments go. The setup is essentially a cylindrical space in which the floor and wraparound wall are made from flexible computer displays. Animals placed into the environment are monitored by overhead cameras and sensors that track their movement and behavior around the 3D space.

The principal benefit of the FreemoVR system is that, as the name implies, the device allows animals to move about freely within the environment. Using specially developed software, the researchers can adjust the visual imagery on the fly, as it were, and project elements based on the animals' behavior and movements in real time.

RELATED: A Universal 'Language' of Arousal Connects Humans and the Animal Kingdom

"The most important thing is that the animal is actually moving and gets all the appropriate mechanosensory feedback," study co-author Andrew Straw, of the University of Freiburg in Germany, told Seeker in an email. "This is really important for studies of navigation and spatial cognition, because if the animal doesn't believe it is moving, it will be difficult to study how the animal updates its 'mental map' as it moves."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new study, published this week in the journal Nature Methods, details a series of experiments that suggest that the lab animals find the virtual reality experience pretty convincing. The animals reacted to virtual images the same as they would to real-world objects and obstacles. The research team chose three animal species often employed in lab studies — mice, fruit flies, and zebrafish — to make the technique more useful to other scientists.

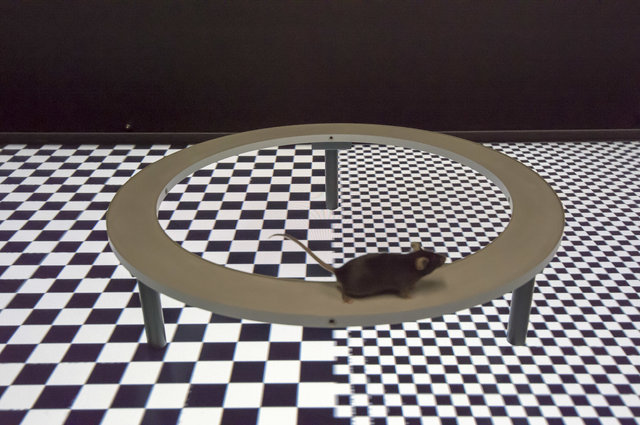

In one experiment, mice were placed atop an elevated platform with a projection screen lying beneath. The display created an illusion of depth, giving the impression that one end of the platform was higher than the other. The mice reacted to the illusory change of height by staying on the lower and "safer" end of the platform.

RELATED: The Color of Your Clothing Could Affect the Behavior of Animals

In another experiment, a tank filled with zebrafish was placed in the FreemoVR system while researchers projected a swarm of descending aliens from the old Space Invaders arcade game. The fish reacted to the incoming swarm as if it were real, and even engaged in mimicking behavior to "join" the swarm.

Tricking fish with old video games may seem like a strange use of the scientific method, but Straw says the experiments can tell us a lot about how animals see the world, which in turn can tell us about human perception — especially in large groups.

"Humans and mammals have a highly conserved overall brain architecture and many close parallels in the systems related to spatial cognition," Straw said. "That's the reason why many labs use these [animal] systems for models. This way, we can do things such as recording from hundreds or thousands simultaneously, which would not be possible in human experiments."

RELATED: The Trail of Antibiotic-Resistant Superbugs Leads Back to the First Land Animals

Incidentally, the holodeck thing is no random pop culture reference. Straw, who has plainly stated that his team's aim was to create a holodeck for animals, grew up watching Star Trek.

"Star Trek: The Next Generation played in almost infinite reruns where I grew up," he said. "Captain Jean-Luc Picard is basically my hero."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus

![The experimenters control the fly's position [red circles] and its flight direction by providing strong visual motion stimuli. Left: live camera footage. Right: plot of flight positions.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/XUoPFQvXMQhHsHZTrzgwoE.jpg)