South African Safari: Wild Beasts of the Cape

The Cape of Africa

A jackal barks and whines nearby, warning me away from its den full of pups. Rock doves and African hoopoes (a colorful bird) purr in the drowsy dawn light, and a lone ostrich walks by on gangly legs bobbing its long neck. This is the quintessential African experience a sensory assault of plants and animals, sights and sounds flavored with the memories of our deepest human origins.Squashed between the warm waters of the Indian Ocean and cooler waters of the Southern Atlantic, the African Cape is one of the most geologically and ecologically distinct regions of the African continent. The varied habitats found throughout the Cape are created by the forces of water and geography constantly mixing. Along the Western Cape, a dry Mediterranean-like climate supports one of the world's richest floral communities called the fynbos while inland the land rises to semi-arid desert in the Karoo region. In the middle, the land rolls away into unbounded grassland called the highveld and the lowveld, while in the northeast grasses give way to scrubland and rotund baobab trees.You can experience this diversity all within the boundaries of modern day South Africa. You can watch penguins play in the cold waters off the Cape of Good Hope, trek over wind-scoured ridge tops in the Drakensburg Mountains, gaze on the open desert of the Kalahari, and safari in the wildlife-rich scrub savanna of the north all within a few days' journey around the Cape.

The Horned One

Some of the rarest big mammals left in the world still hold on in the Cape. As if they were remnants from a bygone age, rhinos exude a prehistoric aura. Something about their craggy horned noses, huge bulk and slow lumbering gate makes them both awe-inspiring and comical, like a fantasy creature come to life.With only a few scattered populations across Africa, rhinos are actually in danger of becoming fantasy creatures. Black rhinos (Diceros bicornis) are an especially rare sight. Once found from the Cape to Kenya, they are now found mostly in protected areas and national parks. Weighing up to 3,100 pounds (1,400 kilograms) they have no natural predators except man. Poaching for their horns highly valued in traditional Chinese medicine has pushed the species to the brink of extinction. Currently, black rhinos are classified as critically endangered throughout their range by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).Black rhinos are also known as the hook-lipped rhino since they use their prehensile lips to nibble twigs and leafy shrubs. In fact, they eat so many shrubs that they transform shrub land to grassland, which is important for other herbivores like gazelle. Often solitary, black rhinos have a reputation for aggressive behavior and will often charge when frightened, irritated or confused. Needless to say, watch out around these guys. Snapping this shot from the back of a truck, I have to admit to being slightly terrified each time the wind changed and he nervously caught our scent!

Rock hoppers

In contrast to huge beasts like rhinos that call the African Cape home, many less intimidating, but equally fascinating, creatures claim the Cape as their habitat. Of the dozens of different species in the antelope tribe that abound in Africa, one of my personal favorites is the diminutive and humble klipspringer (Oreotragus oreotragus).

In Afrikaans the name "klipspringer" literally means "rock jumper." As they are almost always found on or near the ubiquitous rock mounds called kopjes that dot Africa, the name fits. In the local Xhosa dialect these widespread little antelope are also called "umvundla," which means "rabbit." At only about 22 inches (58 centimeters) tall and a few pounds in weight, these small antelope with a penchant for rock jumping really do seem more akin to rabbits than to antelope!Klipspringers, a familiar sight in the scrublands and semi-deserts of the Cape, have adapted so well to eating the sparse desert plants and succulents found here that they never have to drink. Like most creatures here they are simply and elegantly adapted to the land that they belong to. Gazing at you quizzically on their tiny toes, klipspringers are hard not to find amusing and likable.

Horn and hide

Klipspringers may be docile and cute, but some other ungulates found throughout the Cape are not so harmless. Cape buffalo (Syncerus caffer) are huge and dangerous grazing animals. Lumped within what is known around Africa as the "Big Five" buffalo, lion, elephant, rhino and leopard Cape buffalo are feared and revered by big game hunters and locals alike.

Cape buffalo congregate in large herds, cropping the many tall grasses of the savanna as they migrate between summer and winter feeding grounds. One of the most successful grazers in all of Africa, Cape buffalo are found in savanna, woodlands, thorn scrub, swamp and most places with a ready water source nearby.

Unlike their cousins in Asia, the African Cape buffalo's wild and aggressive behavior made it impossible to domesticate. Their unpredictable behavior is notorious throughout Africa and many human deaths have been attributed to them. Noisily pulling up grasses and tussling with one another, a herd of buffalo can make short work of an area. Photographing close enough to smell their pungent breath and see their black hides and scimitar-like horns will quicken your pulse in excitement and fear.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The King

Walking through the dry, knee-high grasses, it is easy to let your fears and insecurities blossom. Behind each bush, hidden in each shadow, and lying in wait just beyond your vision in the tall grass you are being watched.

To walk through an African landscape knowing large and dangerous predators are nearby that consider you part of their food-chain is to imagine what is must have been like for the first humans. Of all the things that stalk the night, no other large predator evokes such strong feelings of fear and awe as the African lion (Panthera leo).

Historically distributed throughout most of Africa into parts of Europe, the Middle East and Southwest Asia, lions were once one of the most widely distributed of all large mammals in the world. Today, because of habitat loss and human conflicts, it is inevitable that their range is restricted to game reserves, national parks and other wild areas with few people.

Weighing in at up to 550 pounds (250 kg), lions are the alpha predators of the Cape region and throughout much of Africa. Their role as top predator helps keep the ecosystem balanced and healthy by weeding out the sick and old from the herds. As large predators hunting in prides, lions can tackle big game like buffalo that other predators cannot, but as opportunists the so called "king of the savanna" is also not above scavenging for an easy meal. Sleepy-eyed with a swollen belly, this big male had obviously had happy hunting the previous night. Just like your languid housecat, he has that on-of-a kind, feline knack for lazing away the afternoon. Male lions take lazing away to new levels, in fact, and have been known to sleep over 20 hours in a day!

The undertaker

If lions help keep the herds healthy by singling out the weak and old, scavengers like the marabou stork (Leptoptilos crumeniferus) keep the ecosystem clean and regular by cleaning up the remains. With a wingspan over 10.5 feet (3.5 meters), marabou storks are huge birds and share the distinction of having the largest wingspan in the world with the Andean condor. Often found near water and widely distributed through Africa, marabou storks and vultures play the inglorious but essential role of ecosystem janitors and recyclers.

Nicknamed the "undertaker bird," marabous are quick to arrive on the scene of a crime and busily clean up the remains of a kill. They may not be the most handsome fellows, but marabous are perfectly evolved for scavenging. Their long ungainly necks, bald heads, and strong sharp beaks are all adaptations for puncturing tough hides, snaking their long necks into carcasses, and gorging on a grisly feast unencumbered by feathers that would otherwise collect blood and attract parasites.

Without scavengers like marabous, the carcasses and waste of the savanna would accumulate and rot, spreading pestilence and disease. Though we may look upon them as grotesque and macabre, scavengers create life from death by recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem.

The clever ones

Naturally curious and moving in large social groups, chacma baboons (Papio ursinus) can find food in unlikely places throughout the Cape's varied ecosystems. Having long ago made the evolutionary jump (no pun intended) from the trees to the ground, baboons forage for seeds and nuts, tubers and plants, and even eggs and meat when they are clever enough to get them. Living on the savanna with so many other big and dangerous animals, baboons have had to rely on their cleverness to survive.

Weighing up to 31 kg, chacma baboons are among the largest baboon species in Africa. They typically form large social groups with distinct and complex hierarchies. If not actively found in trees, they are seldom far from them or perched on rocky outcroppings where they congregate at night for protection. Male chacma baboons are sexually dimorphic from females, meaning they look physically different and are often larger, with long ferocious canine teeth. Ferocious and clever as they may be, baboons still live in fear of some predators, especially their nemesis, the leopard.

Traveling in the Cape, I once met a farmer from Zimbabwe who told me about an amazing site he once encountered in the bush: a whole troop of howling, screaming baboons had cornered a leopard on the outer branches of a large tree. What became of the leopard I do not know, but like many things here, the lesson is that the winds of fate can easily shift from hunter to hunted...

Shadow in the grass

A herd of impala graze nervously, constantly sniffing the breeze for an unseen danger. Like a sun-dappled shadow in the grass, their stalker, the leopard (Panthera pardus pardus), embodies secrecy and stealth. Fluid feline movements, mysterious ways and beautiful camouflage make the leopard the Cape's perfect ambush predator.

Weighing between 75 to 132 pounds (35 60 kg), leopards are mid-sized hunters that prey on a wide variety of small and large game. Leopards adapt to wide-ranging habitats throughout Africa and may be found from rocky desert to thick jungle and places in between. By day, they often lounge in the crook of a tree hidden in their natural camouflage. By night, they hunt and will drag their kills up into the higher boughs of trees, where it is safe from scavenging lions and hyenas.

Walking under the boughs of an acacia tree it is not unusual to see the remains of an impala carcass hanging from a nook in the branches. Leopards are so elusive that such calling cards are often the most anyone ever sees of them. Getting so close to this young male stalking boldly through the early morning tall grass was pure luck and an amazing moment I will never forget!

The wise ones

The African elephant (Loxodonta africanus) fills a unique place in both the African ecosystem and our human imagination. No other creature in the world is made like an elephant. Long serpentine noses, flat prodding feet, huge umbrella-like ears, and a thick impervious hide make them one-of-a-kind. Long-lived and highly intelligent, elephants also have surprisingly complex and sophisticated group social behavior. You could even say elephants have their own "culture," like us.

With a huge bull elephant towering over you in a tiny bush truck, you realize elephants really can be larger-than-life. The role of elephants in the African ecosystem can be so large in fact that their presence or absence changes it. Their natural tendency to push down trees and pull up small shrubs and saplings for food can change a forest into grassland in no time. In this way, elephants can be thought of as "ecosystem engineers" in their ability to change their environment.

Today their huge presence and enormous food needs have put elephants in direct conflict with growing human populations in many parts of Africa. During the 20th century elephants were heavily hunted throughout the continent for their ivory. In some places they disappeared, while in others only small populations remained. Since then, conservation has had mixed results with populations continuing to decline from poaching or habitat loss in some areas, while they have become overpopulated in some protected areas.

Timeless Africa

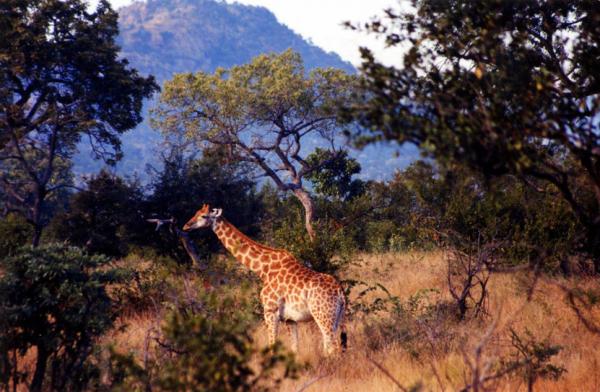

The wildlife of the Cape is as rich and varied as the land itself. A whopping 10 percent of all known plant species are found here, as well as numerous animals that are often scarce in other parts of Africa. What is especially amazing for most visitors, though, is sharing the land with huge wild animals. There is something humbling and awe-inspiring about being up close and personal with a towering giraffe, lumbering elephant or belligerent rhino free and wild in the bush that no zoo could ever come close to replicating.

The Cape's landscape is also ancient, carved out and weathered by age-old forces and home to our own evolutionary origins. Perhaps that is why a visit here is like no place else. The nostalgia and memory of Africa lies dormant somewhere deep inside our very DNA.

As I wander under the fever trees on a bushy ridge top, innumerable clues of passing and going beg to be unraveled. In the chalky dust of the dry season the story of a warthog coincides with that of a leopard, a baboon troop's daily wanderings take shape, and the tiny avenues of mice and small things meet in a labyrinth of unseen tunnels in the grass. Interwoven stories, constantly beginning and ending, but always continuing, are everywhere painted across the African bush if you know how to see them. With a little imagination you can even begin to imagine our own...

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus