In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Crashing to Earth

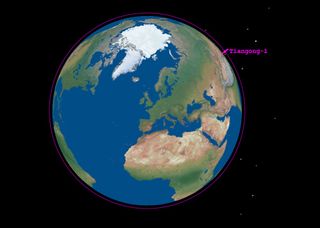

Tiangong-1

China's first space station, Tiangong-1 (which means "heavenly place"), is currently falling back to Earth in what spaceflight insiders call an uncontrolled reentry. The fall from the heavens (or low-Earth orbit) has been a known and planned-for outcome for the bus-size space station. But before we get to the fiery descent, we must rewind six years to when the 18,740-pound (9 tons) space lab was launched into orbit.

Launching Tiangong-1

Tiangong-1 was launched from a Long March 2F/G rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center on Sept. 29/30, 2011, in Jiuquan, Gansu province of China. It measured 34 feet (10 meters) long and 11 feet (3.4 m) in diameter, with a paddle-like structure covered in solar panels on either side.

Shenzhou-9

After launching aboard the Chinese Long March 2F rocket, Shenzhou-9 was initially boosted to a "parking orbit," before being put into a nearly circular orbit above Earth. It took two days for Shenzhou-9 to get close to Tiangong-1.

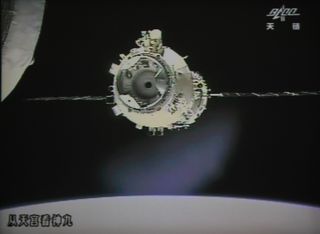

Docking with Tiangong-1

On Nov. 3, 2011, China's Shenzhou-8 spacecraft docked with the Tiangong-1 lab module.

China space station

This artist's illustration from a China space agency video shows the Tiangong-1 space laboratory, which is considered a prototype module for the country's planned space station.

Daring descent

Like other objects circling our planet in low-Earth orbit, Tiangong-1 has been at the mercy of Earth's gravitational tug and atmospheric drag. As such, over time, without any boosting maneuvers, objects like China's space lab naturally get closer and closer to the planet's surface — their altitude decreases.

Lost link

Initially, China had planned a controlled descent of Tiangong-1 using what is called a thruster burn, or controlled maneuvering with its thrusters, to descend back to Earth. But Tiangong-1 had other plans, and on March 16, 2016, China alerted the United Nations that it had lost its telemetry link with the space station — that meant China could no longer control the lab's inevitable descent.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

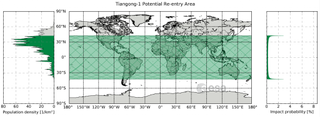

Lab's reentry

This image from the European Space Agency shows the region where Tiangong-1 is expected to reenter Earth's atmosphere.

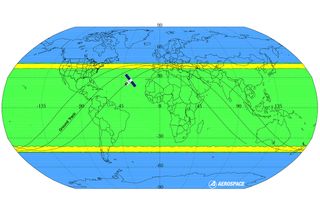

Odds of getting hit

The Aerospace Corporation has estimated the most probable location of Tiangong-1's reentry. The yellow bands are the riskiest places to be, but even there the odds of getting hit by space station debris are extremely low.

Space capsule

This photograph of a China CCTV broadcast shows the Shenzhou-9 space capsule lying on its side after landing in an autonomous region of China in Inner Mongolia on June 29, 2012, to end the 13-day mission to the Tiangong-1 space lab module.

Approaching the lab

A photo of the giant screen at the Jiuquan Space Center shows the Shenzhou-9 spacecraft approaching Tiangong-1 module for the automatic docking on July 18, 2012.

Jeanna served as editor-in-chief of Live Science. Previously, she was an assistant editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Jeanna has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland, and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Most Popular