'Mic'd Up' Underwater Volcano Offers Unique Glimpse of Submarine Eruptions

SAN FRANCISCO — Though volcanoes dot the face of the planet and can be found on every continent, researchers say most of Earth's volcanic eruptions happen in a dark and faraway place: deep underwater. And now, last year's eruption of one of the most active submarine volcanoes is offering clues about these explosive processes, which could help scientists better understand volcanoes on land, including those that pose serious threats to humans.

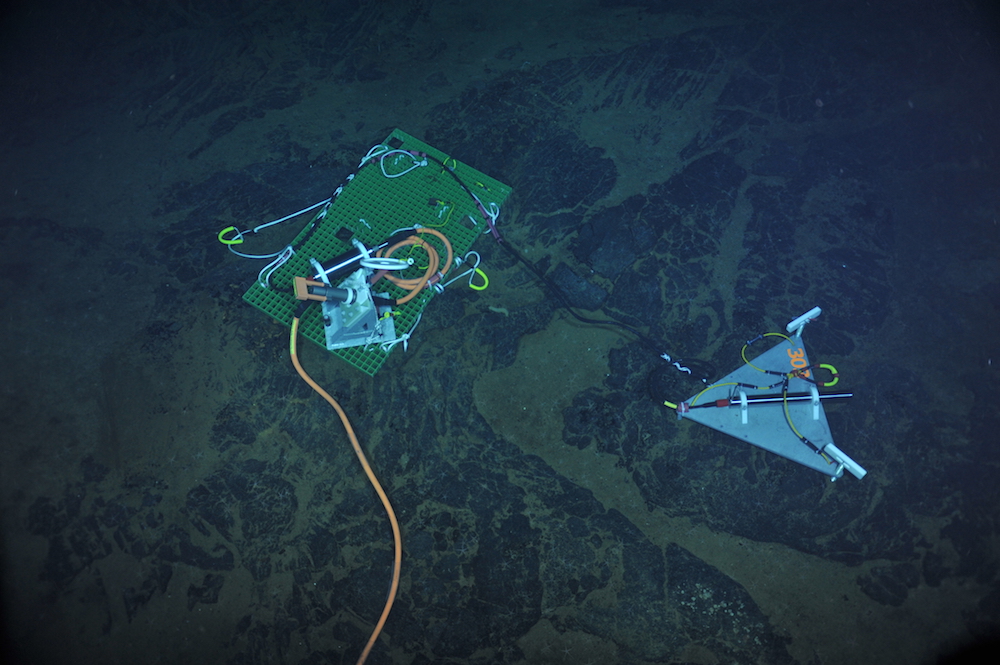

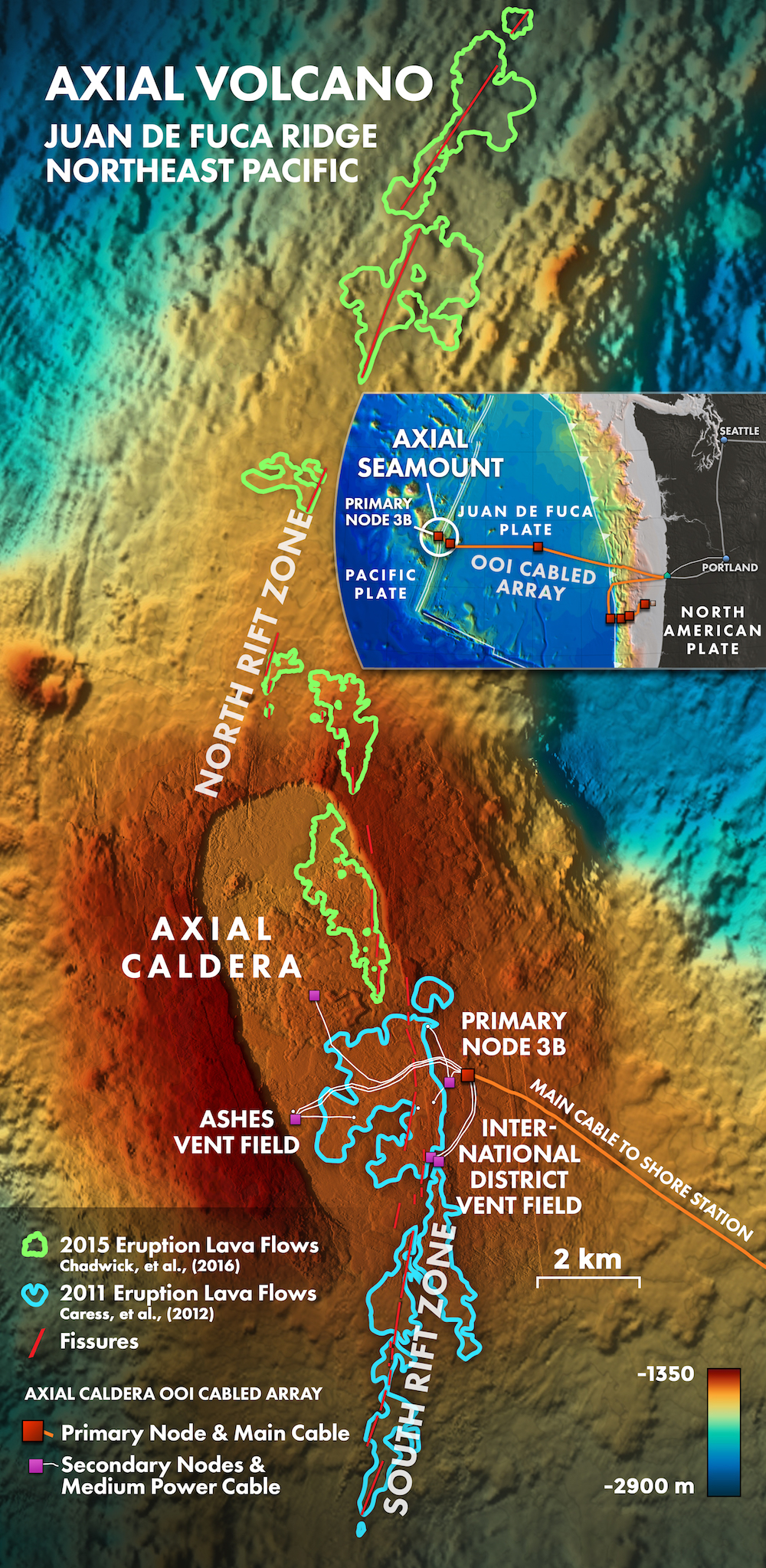

In April 2015, an underwater volcano known as Axial Seamount erupted 290 miles (470 kilometers) off the coast of Oregon. Thanks to a network of underwater sensors, scientists were able to study the submarine volcano more closely than ever before. The researchers presented some of the first scientific results from that eruption in a news briefing here today (Dec. 15) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Axial Seamount's previous eruptions, in 1998 and 2011, prompted scientists to deploy a network of seven seismic stations to study the volcano. The so-called Ocean Observatories Initiative Cabled Array went online in 2014, and initial observations from these sensors (combined with consistent monitoring of the mile-high volcano for almost two decades) led researchers to correctly predict that Axial Seamount would erupt sometime in 2015. [Axial Seamount: Images of an Erupting Undersea Volcano]

One observation that aided this prediction was the patterns of seafloor deformation — surface changes caused by the movement of magma, according to study co-author Scott Nooner, a geologist at the University of North Carolina.

"As the volcano is recharged with magma, the surface of the volcano swells like a balloon," Nooner said. "Then during an eruption, the magma is taken out of the underlying magma chamber and the surface of the volcano drops."

The scientists also observed increased seismicity leading up to the April eruption. Before the volcanic event, the frequency of minor earthquakes near the volcano increased from fewer than 500 per day to about 2,000 per day, they said.

Beyond the seismic sensors and seafloor mapping, there is an entire network of other instruments that make up the volcano's underwater observatory. From cameras and temperature measurements, to instruments that collect data about the chemistry and biology of the volcanic area, this network will make Axial Seamount one of the world's most well-studied volcanoes, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Though far from posing a threat to human lives, the underwater eruption of Axial Seamount is very turbulent.

"Underwater volcanoes make a mess," said research partner David Clague, a geologist and volcanologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, California. "The water column is full of small particles that are emitted during the eruption, bits of glass and bacteria from the subsurface."

Even months after an eruption event, researchers can still have difficulty studying the volcano because of the cloudy water, they said.

One of the next phases of the research will investigate how local ecosystems are affected by such an explosive eruption.

"When this volcano erupts the next time, we will have an even larger data set than we have now," said study co-author William Wilcock, a geologist at the University of Washington. "We will be able to observe not only the geophysics of the eruptions, but we will be able to understand how the hydrothermal systems and the life systems they support are impacted by the eruption and we'll be able to do that in real time."

By closely monitoring Axial Seamount, the scientists are gaining a better understanding of volcanic activity in general. Their research could be applied to land-based volcanoes, which can have deadly eruptions. Scientists are able to make only short-term eruption forecasts for land-based volcanoes — typically a few weeks in advance. But Nooner said the models used to forecast last year's Axial Seamount eruption months in advance could one day be refined for terrestrial volcanoes.

The research was detailed in two papers published online today (Dec. 15) in the journal Science and one paper published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Original article on Live Science.