Sunken Treasure Ship Worth Billions Possibly Found After 300 Years

The wreck of a lost treasure ship has been found 307 years after it vanished beneath the waves.

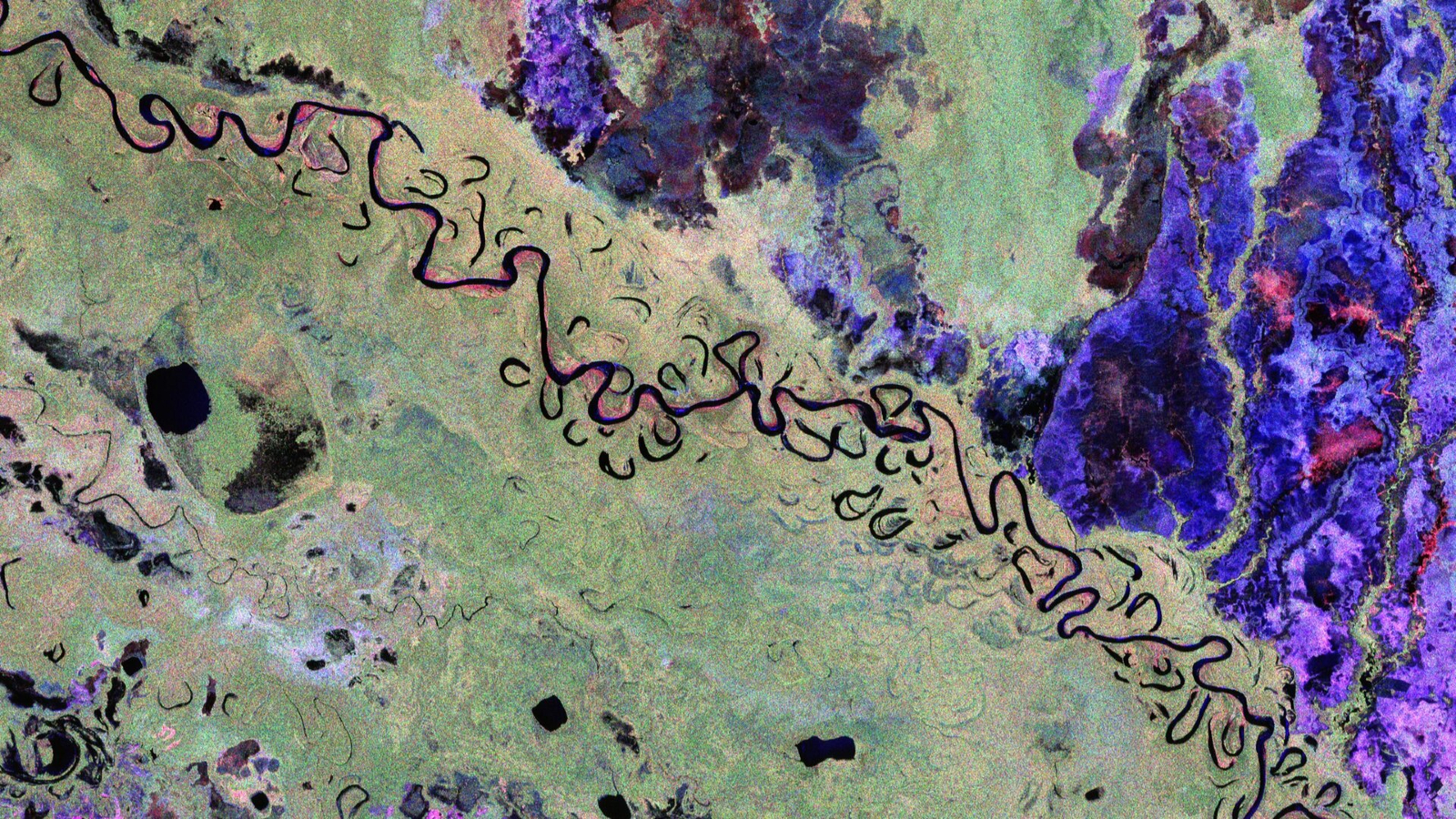

The galleon San Jose was found at the bottom of the Caribbean off the Colombian coast on Nov. 27, President Juan Manuel Santos of Colombia said in a statement on Saturday (Dec. 5). Built in 1696, the Spanish galleon was lost in a sea battle with the English in 1708.

A modern battle seems likely to erupt over the find. As CNN and other outlets reported, a U.S. salvage firm has claimed that it originally discovered the site of the wreck in 1981 and is owed half the treasure on the ship — a haul of gold and silver from South America thought to be worth between $4 billion and $17 billion. [See Photos of the 'San Jose' Treasure Ship and Artifacts]

The Colombian government has not released the precise location of the wreck, nor much information about the discovery process.

"While this is an extremely exciting find, I'm anxious to see more of the archaeological evidence and what characteristics of the shipwreck were used to come up with the identification," Frederick "Fritz" Hanselmann, an underwater archaeologist at Texas State University who studies shipwreck sites, told Live Science.

The San Jose was a 1,066-ton behemoth of a ship, which was equipped with 60 cannons and held a stash of gold and silver coins and emeralds from the mines of Peru. This treasure was ultimately headed to Europe, where it would fuel the long-running War of Spanish Succession, a conflict that pitted the Spanish and French against the English.

According to a history of the San Jose introduced into the court proceedings between the Colombian government and the salvage firm claiming part ownership of the wreck, the San Jose held a particularly huge haul of treasure. Earlier in the war, Spanish armadas had escorted treasure ships back to Europe annually. But after the English fleet ambushed an armada in northern Spain and wiped it out, small French warships took over the responsibility of moving gold, silver and precious gems in smaller loads across the Atlantic Ocean.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The San Jose was part of the first armada to undertake the Atlantic crossing in six years. The King of France, Louis XIV, needed the treasure to fund the war, and ordered a French fleet to accompany the San Jose and three other galleons across the ocean. (In addition, 11 smaller Spanish ships guarded these four huge warships.)

Ultimately, however, the French escorts were delayed, and the commander of the Spanish fleet, Admiral Jose Fernandez de Santillan, Count of Casa Alegre, decided to go it alone. [Shipwrecks Gallery: Secrets of the Deep]

With more than 500 men crewing the ship, the San Jose set sail on its last voyage on May 28, 1708, carrying a full half of the treasure. The armada was headed for Cartagena, Colombia, en route to Havana and then Europe, but ran into four English ships commanded by Commodore Charles Wager.

Unable to outrun the English, Alegre and his armada reluctantly prepared to fight. A cannon battle ensued; as outlined in the court history, the decks of both Wager's warship and the San Jose grew slick with blood, and the crews of both ships threw down sand to improve the footing on deck.

Suddenly, the San Jose erupted into a fiery conflagration and sank. Accounts vary on whether this was due to an explosion of the ship's powder room or a structural collapse and fire that were caused by the British bombardment. (The ship was already leaking and had a compromised hull because of damage by rot and worms.). According to the Colombian government, an archaeological study of the wreck could answer this question.

About 600 men died when the San Jose went down, including Admiral Alegre. The court history recalls the tragedy:

"Six hundred lives had been destroyed in an instant. Most of them, including Alegre, either were vaporized in the explosion or went to the bottom of the Caribbean with the tons of precious metal which had been destined to finance the killing of thousands more on the battlefields of Europe."

According to the office of the Colombian president, archaeologists identified the shipwreck of the San Jose with certainty by its cannons. The discovery was managed by the Colombian Ministry of Culture and the Colombian Institute of Anthropology and History, as well as by "international experts," whom the government declined to identify. Perhaps because of the assumed value of the treasure onboard, the government also refused to pinpoint the resting spot of the wreck, other than to say that it was found in a location not previously identified as the site of the San Jose.

The U.S. firm Sea Search Armada claimed to have found the San Jose in 1981, a claim that has led to a long legal battle between the salvage group and the Colombian government. The Colombian government claims that the Colombian court system has found that it does not have to split the treasure with Sea Search Armada; however, in a statement to CNN, Sea Search Armada argued that the matter remains undecided.

According to The Guardian newspaper, there may be another claimant waiting in the wings: Spain is weighing action to reclaim its "sunken wealth."

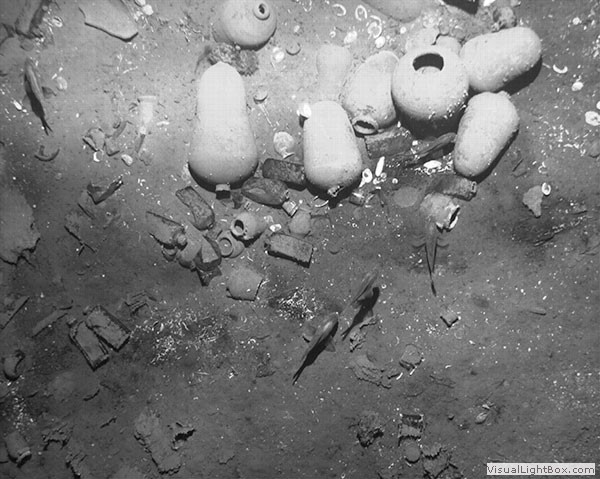

The exploration teams used sonar and an autonomous underwater vehicle to find the ship. Parts of the original structure are visible on the ocean floor, according to the president's office, along with ballast, bronze cannons, ceramics, porcelain vases and weapons.

It's these humble items that excite archaeologists more than silver and gold. The positions and use of military and galley items can reveal a great deal about how sailors employed by the far-flung Spanish empire lived their daily lives, said Justin Leidwanger, a professor of classics at Stanford University who studies Mediterranean shipwrecks and ports.

"From a history of technology standpoint, it could be huge for telling us a bit more about how Spain was able to hold on to a global empire," Leidwanger told Live Science.

Editor's note: This article was updated on Dec. 9 at 12:30 p.m. ET to add quotes from archaeologists Hanselmann and Leidwanger.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus