Last US Atom Smasher on Chopping Block

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Until recently, the American particle collider was a thriving species spanning a variety of habitats from coast to coast. But now it finds itself on the endangered list.

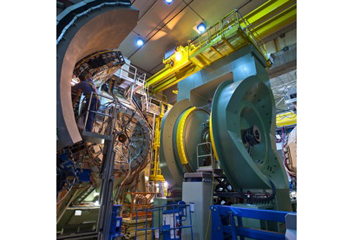

Since 2008 the number of colliders in the U.S. has dwindled from four to one. And the last surviving member of the species, the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory in Upton, N.Y., may soon fall victim to the same budgetary blight that has already felled so many other towering scientific facilities. Just last year the U.S. Department of Energy (DoE) phased out the larger Tevatron collider at Fermilab in Illinois, citing fiscal constraints. The increasingly rare breed known as the collider is a particle accelerator in which two beams of high-energy particles intersect to collide head-on inside giant detectors, which allow physicists to sift through the wreckage for short-lived particles or evidence of new physical phenomena.

The RHIC collider is one of three major projects now under scrutiny as federal science agencies seek to reconcile their portfolios of physics facilities with tightening budgets. The DoE and the National Science Foundation have requested that a panel of nuclear physicists, chaired by Robert Tribble of Texas A&M University, advise the government on how to get the most science out of limited funds. It appears likely that at least one of the costly projects—either RHIC, the Thomas Jefferson National Accelerator Facility in Virginia or the planned Facility for Rare Isotope Beams (FRIB) in Michigan—will fall victim to the cost-cutting. Any termination would cost hundreds of jobs and affect thousands of scientist users.

"The three of these things … they can't all fit within the budgets that the DoE has been told to anticipate for the next five years or so," says Steven Vigdor, associate laboratory director for nuclear and particle physics at Brookhaven. "It's conceivable, but I think it's a long shot, that there's a compromise solution that doesn't involve terminating something."

The RHIC collider, with a staff of about 750, could provide the biggest target for cost-cutters. Its operation costs the DoE roughly $170 million annually. But RHIC is also the only facility of the three that is currently in operation, and it seems to be hitting its peak, having recently been upgraded. RHIC rams protons or heavy nuclei from gold, copper or uranium atoms together at nearly light speed to investigate what produces the proton's spin as well as the universe's composition in the earliest instants after the big bang. The high-speed collisions of heavy ions produce a nearly frictionless fluid called a quark–gluon plasma, a hot bouillabaisse of the fundamental particles that form the heart of all atoms. Quark–gluon plasma was first produced at RHIC in 2005, and scientists there are now working to explore at which temperatures the quarks and gluons freeze out from their fluid state into protons and neutrons.

Like the other two facilities, RHIC comes highly recommended by nuclear physics advisory groups. A 2012 report by the National Research Council identified the completed RHIC upgrade, and an ongoing upgrade at Jefferson Lab, as strategic investments whose exploitation "should be an essential component of the U.S. nuclear science program for the next decade."

The Tribble panel operates under the auspices of the Nuclear Science Advisory Committee (NSAC), which provides guidance to the federal funding agencies. Tribble's subcommittee will meet in Maryland over four days in early September, during which time representatives of the various facilities will have an opportunity to lobby for their projects. "We and the other laboratories are taking this really seriously in the sense of a threat to our continued operation, and for FRIB to their continued construction," Vigdor says.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Each of the labs has a unique case to make: A 2007 long-range plan drafted by NSAC, for instance, highlighted the Jefferson Lab upgrade as the top priority for U.S. nuclear physics. That upgrade, which will double the energy of the electron beams in the lab's particle accelerator, is roughly two thirds complete, says Robert McKeown, deputy director for science at Jefferson Lab. And the machine already has seven to 10 years of experiments queued up for when it returns to active service sometime after 2015. The Jefferson accelerator explores several questions relating to the structure of the atomic nucleus, including how the fundamental particles of matter, quarks and gluons are bound up inside protons and neutrons. The lab received about $160 million this year from the DoE, including $50 million in construction funds for the facility upgrade.

Unlike Brookhaven, which hosts a number of large experiments, Jefferson Lab would essentially cease to exist if its accelerator were defunded. "We're a single-purpose laboratory," McKeown says. "So the situation would be very different for us if the decision were made not to continue our electron accelerator." Some 700 jobs depend on the lab's continued operation.

Michigan State University's planned FRIB (pronounced "eff-rib"), earned the second-highest slot in the 2007 ranking of nuclear physics priorities. The machine would produce on demand a variety of exotic isotopes—often unstable versions of chemical elements with abnormal numbers of neutrons in the nucleus. FRIB would investigate the origins of the elements that constitute our physical world, many of which are born in the cores of stars and in supernova explosions, and could quickly churn out isotopes for medical research and the development of advanced imaging technologies.

The facility is still in the design phase, and though the DoE has not issued formal schedule and budget, preliminary estimates peg FRIB as a 10-year project costing more than $600 million. Once built, however, its operations costs would potentially be lower than those of either Jefferson Lab or RHIC, and its staff would be much smaller. "But being the cheapest may not really be germane here," says FRIB project manager Thomas Glasmacher, a nuclear physicist at Michigan State. "It's kind of like comparing apples and eggs or something like that. It's different science, and they're different experiments."

In interviews, the three lab representatives took pains not to disparage the other facilities, choosing instead to highlight the upsides of their own respective experiments. "We are all on each other's advisory committees," Glasmacher says. "It's a very small community." All three facilities are highly touted and in high demand—even FRIB, which will not exist for many years under the best of circumstances, already has more than 1,000 scientists signed on to its user group.

Shuttering any of those projects will disrupt a field in which, as McKeown puts it, "the U.S. maintains the frontier facilities and has substantial leadership throughout the world." It falls to the Tribble panel to choose which of three unpalatable options is the least so. "I don't envy anybody on the panel," Glasmacher says.

Brookhaven's Vigdor echoes that sentiment. "It’s hard to predict how things are going to come out, because there are no easy solutions right now," he says. "Every possible solution carries a lot of pain."

This article was first published on Scientific American. © 2011 ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved. Follow Scientific American on Twitter @SciAm and @SciamBlogs. Visit ScientificAmerican.com for the latest in science, health and technology news.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus