7,000-year-old animal bones, human remains found in enigmatic stone structure in Arabia

Researchers have discovered human bones and animal remains dating to around 7,000 years ago in Arabian stone structures known as mustatils.

Archaeologists excavating an ancient stone monument in Saudi Arabia have unearthed thousands of animal bones, as well as human remains belonging to at least nine individuals.

The discoveries suggest that people gathered at stone structures to perform rituals and activities in Saudi Arabia about 7,000 years ago. These rituals appear to have included depositing animal horns and skulls.

More than 1,000 prehistoric rectangular stone structures called mustatils ("rectangles" in Arabic) have been documented in Saudi Arabia, yet exactly when and why they were built have remained a mystery. In 2018, the Royal Commission for AlUla, a region in northwest Saudi Arabia, launched a project to document and study mustatils and other archaeological remains in the region.

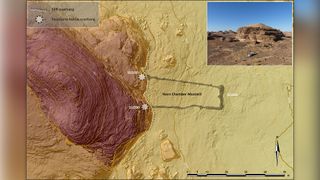

The recently excavated mustatil measures 131 by 39 feet (40 by 12 meters); the stone walls are up to 6.6 feet (2 m) thick, but the original height of the walls, which have since eroded, is unclear.

At the center of a courtyard within the mustatil, there is a structure that may have functioned as a shrine, with two hearths where ceremonies may have taken place, the archaeologists wrote in a paper published in August in a supplement to the journal Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies.

Related: 7,000-year-old cult site in Saudi Arabia was filled with human remains and animal bones

Within the mustatil, archaeologists also found more than 3,000 fragments of animal remains that together weigh about 55 pounds (25 kilograms). These animal remains include hundreds of horns and heads of animals, including cattle and caprines such as goats. Other prehistoric sites in the Middle East also contain a multitude of cattle heads and horns, including a site in Yemen where a ring of cattle skulls was displayed, lead study author Wael Abu-Azizeh, a junior professor of archaeology at Lumière University Lyon 2, told Live Science. The animal bones were deposited between 5300 B.C. and 5000 B.C., the archaeologists wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The human bones found in the mustatil come from at least nine people: two infants, five adults, an adolescent or young adult, and a child, the team wrote in the paper. The human remains date to a few centuries after the animal bones were placed in the mustatil. "It's a collective burial," and it's unclear if the people buried there are related to the builders of the mustatil, Abu-Azizeh said.

Olivia Munoz, an archeo-anthropologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) who wasn't involved with the study, praised the research and hopes that more details about the human remains will be published. "It would be interesting to know the distribution by bone type to help understand whether individuals were deposited whole or whether parts of the already decomposed skeleton could be brought into [the mustatil]," Munoz told Live Science in an email.

Religious meaning

It's unclear why the mustatil was created and why it holds so many animal bones. In a 2021 paper published in the journal Antiquity, researchers suggested that mustatils may have been part of a "cattle cult" in the region. However, Abu-Azizeh said he disagrees with this idea, noting that the team's excavations found that cattle bones accounted for only a small proportion of the animal remains from the site, with caprines making up the most.

The mustatil's "wide open-air courtyard" design indicates that crowds congregated there. The presence of many animal horns and head remains hints that rituals may have taken place there. Moreover, the two hearths in the possible shrine and the finding that some of the animal bones were burnt suggest that the ritual may have involved the burning of animal bones.

One important aspect of the site is that it is well preserved, said Anne Porter, an assistant professor emerita of Near Eastern archaeology at the University of Toronto who wasn't involved in the work. "All too often open-air structures such as this, wherever they are found, are badly disturbed," Porter told Live Science in an email.

At the time the mustatil was built, the environment in the region would have been substantially wetter than it is today, Gary Rollefson, a professor emeritus of anthropology at Whitman College in Washington, told Live Science in an email. He agreed the mustatil likely had spiritual importance for the people who used it, noting that the animal horns and heads may have been "votive offerings." Nomadic groups that were dispersed much of the year may have gathered at the mustatil at a point in time, perhaps near or just after the end of the rainy season, Rollefson said.

The mustatils will be a part of the AlUla World Archaeology Summit, which will take place Sept. 13-15.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Most Popular