Triassic dinosaur with giant 'murder feet' wasn't so big after all, scientists find

My, what big feet you have.

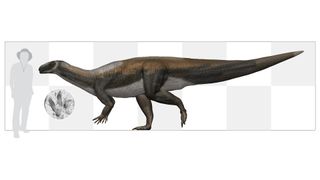

A dinosaur that lived in Australia 220 million years ago left behind footprints that hinted that it was a fierce predator. But a new analysis of the tracks suggests that the animal wasn't a hefty meat eater, as scientists thought when they first analyzed the tracks more than 50 years ago. Rather, it was a smaller, long-necked vegetarian, the new study discovered.

Scientists previously estimated that the alleged carnivore that left the prints had legs measuring at least 7 feet (2 meters) tall at the hip and a body at least 20 feet (6 m) long. At the time of their discovery, the prints were thought to represent the earliest evidence of big predatory dinosaurs, researchers recently reported.

But when they re-examined the tracks, they found that the shape and proportions of the three-toed foot were unlike those of other theropod dinosaurs — bipedal meat eaters — at the time, and were probably made by a smaller type of plant-eating dinosaur called a prosauropod, according to the new study.

Related: In images: Tyrannosaur trackways

Prosauropods sometimes walked on four legs and sometimes walked on two, and they are thought to be ancestors of the giant long-necked and herbivorous sauropod dinosaurs, such as Diplodocus and Apatosaurus, according to the University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley.

To date, footprints represent the only evidence in Australia of dinosaurs from the Triassic period (251.9 million to 201.3 million years ago). Coal miners discovered the newly analyzed tracks in the roof of a mine in 1964, 699 feet (213 m) below the surface, and the individual footprints measured between 16 and 17 inches (40 and 43 centimeters) in length, the scientists wrote in the study.

"It must have been quite a sight for the first miners in the 1960s to see big, bird-like footprints jutting down from the ceiling," lead study author Anthony Romilio, a paleontologist and research associate at The University of Queensland in Australia, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hundreds of millions of years ago, the plant-eating dinosaur squished its feet deep into a swampy surface of wet plants and silt. Over time, sediment filled in the tracks and hardened to preserve the impressions; the plants underneath then transformed into coal, and the sand covering the tracks turned to sandstone, Romilio told Live Science in an email.

"The coal miners removed the coal and revealed a sandstone ceiling, complete with giant 'chicken' footprints," Romilio said.

In 1964, geologists with the Queensland Museum mapped and photographed the trackway and made plaster casts of two footprints. As the mine is now closed, the tracks are no longer directly accessible, the scientists wrote. Only one of the casts survived to the present, in the collection of the Queensland Museum (the whereabouts of the other is unknown), and the scientists used that cast to create a high-resolution digital 3D model of the foot.

They compared the model and measurements of the footprint images with those of other dinosaur footprints from the Triassic, and found that their print differed from those of Triassic theropod dinosaurs (fossilized footprints from this group are known as Eubrontes).

Theropod footprints are usually long and narrow; by comparison, this print was "too wide" to belong to a theropod, Romilio said. The toes of predatory dinosaurs typically bunch together, but in this footprint they were spread wide.

"And the middle toe didn’t project nearly as much as it should have if it were made by a predator," Romilio added. The trackway also rotated inward — a feature that theropod trackways lacked.

"Other things — like how the toes were curved, the presence of enlarged toe pads, as well as an indentation on the outside of the footprint — collectively pointed to a very different shape of footprint. Instead of resembling the theropod track called Eubrontes, our track looked like tracks named Evazoum," Romilio explained.

"Interestingly, the existing hypothesis is that Evazoum were made by ancestral long- necked dinosaurs — prosauropods," he said.

The authors also found that earlier interpretations of the print likely overestimated how big the toes were, because they included impressions made by the foot's dragging claws, which enlarged the footprint's overall length by as much as 35%. Their new estimate placed the dinosaur's hip height at no more than 4.6 feet (1.4 m) and the body length at about 20 feet (6 m).

But even though the new findings reveal that the dinosaur was a smaller vegetarian and not "a scary Triassic carnivore," the discovery is still significant and exciting, study co-author Hendrik Klein, a researcher with the Saurierwelt Paleontological Museum in Neumarkt, Germany, said in the statement.

"This is the earliest evidence we have for this type of dinosaur in Australia, marking a 50 million-year gap before the first [known] quadrupedal sauropod fossils," Klein said.

The findings were published Oct. 21 in the journal Historical Biology.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.