10 amazing things we learned about our human ancestors in 2022

From when our ancient relatives began walking on two feet to the first known medical amputation on Homo sapiens, here's what we learned in 2022 about our human ancestors.

Humans are exceptionally diverse, but we all have something in common: We're Homo sapiens, and we share a common ancestor. But the story of how we arose, spread around the globe and acted along the way is still emerging as scientists find new clues. Here are 10 remarkable things we learned about ancient humans in 2022, and how they affect our understanding of humanity's journey.

1. New 'Out of Africa' development

The discovery of a 1.5 million-year-old vertebra from Israel hints that early humans migrated out of Africa not in one but multiple waves. It's unknown which human species the bone belongs to: Although there is just one human species today, there used to be multiple species in the genus Homo. Previously, researchers found evidence that a now-extinct human species left Africa for Eurasia at least 1.8 million years ago, and there's evidence that modern humans left Africa as early as 270,000 years ago. Now, the discovery of this vertebra (the oldest human bone ever found in Israel), reveals that humans likely left the African continent multiple times.

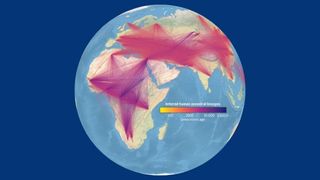

2. Planet-size family tree

Doing your own family tree is hard enough; now, researchers have attempted to do a family tree for all of humanity to see how everyone is related. In their investigation, the scientists looked at thousands of genome sequences from 215 populations from around the globe — including from ancient and modern humans, as well as our ancient human relatives. A computer algorithm looked at genetic variations among genomes, enabling the team to see who was descended from and related to whom. After approximating where these ancestors lived, the researchers created a map for this gargantuan family tree. As one might expect, it all goes back to Africa.

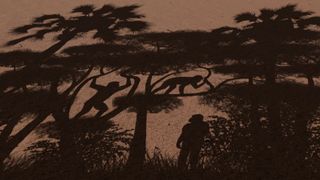

3. Doing the 2-step (7 million years ago)

Walking on our own two feet is quite a feat, one that was pulled off by our ancestors as far back as 7 million years ago, researchers found. The discovery was made when researchers studied a thigh bone and a pair of forearm bones from the 7 million-year-old Sahelanthropus tchadensis, which may be the oldest-known hominin — a relative of humans dating from the period after our ancestors split off from those of modern apes. It appears that S. tchadensis, who was found in Chad, both walked on two feet and also climbed trees.

4. Oldest-known human relative in Europe

A 1.4 million-year-old jawbone found in Spain may belong to the oldest-known human relative in Europe, researchers found. The upper jawbone has features that showcase the evolutionary pattern of the human face, suggesting that it's closer to modern humans than it is to ape-like primates. It's possible that this jawbone belongs to Homo antecessor, whose position in the human family tree is controversial but may be a cousin of modern humans and Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis). Until this finding, the oldest-known human relative in Europe dated to 1.2 million years ago.

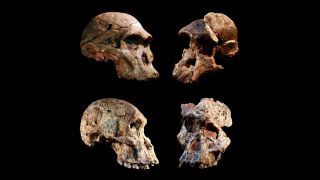

5. Redating bones rewrites evolutionary history

A new analysis of old, human-like bones revealed they may be more than 1 million years older than previously thought, researchers found. The new date range — 3.4 million to 3.7 million years old — of these Australopithecus bones from Sterkfontein, South Africa, improves the odds that this species gave rise to humans. (Sterkfontein is known for its Australopithecus africanus remains, but it's unclear if the studied bones belong to this species.) If true, the finding could rewrite our understanding of how humans arose: The fossils would predate the iconic "Lucy" fossil — a 3.2 million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis in East Africa whose species was a prime contender for being our direct ancestor.

6. Mysterious human relative lived in Southeast Asia

Not much is known about the Denisovans, but along with Neanderthals, they're the closest extinct relatives of modern humans. Precious few fossils exist from these humans, who are named after Denisova Cave in southern Siberia where their first-known remains were found. Over the years, their bones have also been found in China. Now, the discovery of a 164,000-year-old tooth from Laos reveals that the Denisovans also lived in Southeast Asia at low altitudes where it was warm and humid.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

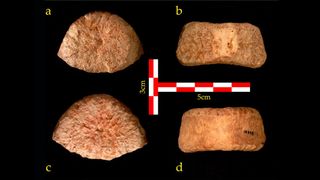

7. Medical amputations happened 31,000 years ago

The oldest medical amputation on record is prehistoric, dating to a Stone Age patient who lost a leg in Borneo 31,000 years ago, researchers found. A skilled surgeon cut off a child's leg, whose stump showed signs of healing. That child hunter-gatherer went on to live for another six to nine years after the surgery, according to an analysis of the individual's tooth enamel. Previously, the oldest medical amputation on record dated to 7,000 years ago.

8. Ice age wall in the way

A massive icy barrier that stood up to 300 stories tall may have blocked the way of the people who left Eurasia to become the first Americans. The existence of this frigid obstacle suggests that these people didn't cross the Bering land bridge from Asia to America on foot, but rather sailed on boats along the coast. Researchers came to this conclusion after analyzing 64 geological samples from six locations across the ancient bridge area. They found that the ice-free corridor didn't completely open until about 13,800 years ago — a confusing date given that other evidence suggests the first Americans arrived much earlier and that the Clovis culture found in New Mexico was already established at that time.

9. Ice age kids splashed in muddy puddles

Little kids today love running around and splashing in muddy puddles, and children from the last ice age were no different. Researchers found about 30 footprints from young children on top of track marks left by a giant sloth, one of the big creatures that once lived in the Americas. These 11,000-year-old prints, found in what is now New Mexico, suggest that the sloth's prints had become muddy, creating a prime spot for jumping.

10. Ancient superhighway was a hotspot in the UK

Thousands of years ago, ancient humans and animals left their footprints on a coastal stretch in England that researchers are calling a superhighway. Some of the tracks are about 8,500 years old, just a few thousand years after the last ice age ended. In addition to humans, researchers found the tracks of aurochs (an extinct ox species), red deer, wild boars, wolves, lynx and cranes. Based on the configuration of some of the human footprints, it's possible that these ancient people were hunting the species of animals whose prints are also preserved.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular