Secret to This Dead Sea Scroll’s Incredible Preservation — And Inevitable Destruction — Could Be Salt

The Temple Scroll is the best preserved of all 900 Dead Sea Scrolls, and researchers just got one step closer to figuring out its secret.

The Dead Sea Scrolls are a marvel. Buried for roughly 2,000 years under piles of debris and bat guano in a chain of caves in the Judean desert, the collection of nearly 1,000 fragmented manuscripts includes biblical texts, ancient calendars and early astronomical observations.

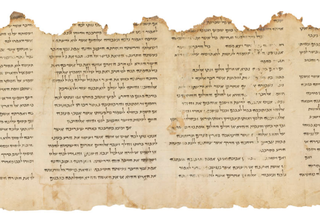

Among these mysterious artifacts (many of which are now just ragged scraps of parchment) one impeccably preserved document stands out. The Temple Scroll, named for its description of a Jewish temple that was never built, is one of the longest (it stretches 25 feet, or 8 meters, long), thinnest and easiest scrolls to read.

Why, out of thousands of faded fragments found in the Judean caves, has the Temple Scroll fared so well after two millennia? In a new study published today (Sept. 5) in the journal Science Advances, researchers attempted to find out by scrutinizing a piece of the parchment using every X-ray and spectroscopic tool at their disposal. They found that the scroll did indeed have something its ancient siblings did not — traces of a salty mineral solution not present in any other previously studied scroll, nor in any of the caves or in the Dead Sea itself.

Related: Gallery of Dead Sea Scrolls: A Glimpse of the Past

According to the researchers, the presence of these minerals shows that the Dead Sea Scrolls were produced using an impressive variety of techniques — and, more importantly, the find could also inform the way these scrolls are preserved in the future.

"Understanding the properties of these minerals is particularly critical for the development of suitable conservation methods for the preservation of these invaluable historical documents," the researchers wrote in the study.

Prior studies revealed that the Temple Scroll was unlike most other Dead Sea fragments, in that it was composed of several distinct layers: an organic layer, made of the animal skin that served as the parchment's base; and an inorganic layer of minerals that may have been rubbed on during a parchment "finishing" process. While all of the Dead Sea Scrolls boil down to animal skins — usually taken from cows, goats or sheep before being scraped clean and stretched on a rack — few showed evidence of finishing, the researchers wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To figure out what this inorganic layer was made of, and whether it was rubbed there intentionally, the team studied a fragment of the Temple Scroll using X-ray scans and Raman spectroscopy — a technique that reveals the chemical composition of a substance by watching how laser light scatters off various chemical elements. They found that the scroll was coated in a mixture of salts made from sulfur, sodium, calcium and other elements. However, these salts did not match elements found naturally on the cave floor or in the Dead Sea, ruling out a natural origin.

The Temple Scroll, the authors concluded, must have been finished in an unusual way that was not used on any other known Dead Sea Scrolls. It's possible that this salt coating has contributed to the Temple Scroll's uniquely well-preserved appearance, the team wrote — but, meanwhile, it could also be an ingredient in the scroll's eventual destruction. Because the salts detected on the scroll are known to suck moisture out of the air, their presence could "accelerate [the scroll's] degradation" if not stored properly, the authors said.

- 24 Amazing Archaeological Discoveries

- 30 of the World's Most Valuable Treasures That Are Still Missing

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space/physics editor at Live Science. His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. He enjoys writing most about space, geoscience and the mysteries of the universe.