Bronze Age Tarim mummies aren't who scientists thought they were

The mysterious Tarim mummies of China's western Xinjiang region are relics of a unique Bronze Age culture descended from Indigenous people, and not a remote branch of early Indo-Europeans, according to new genetic research.

The new study upends more than a century of assumptions about the origins of the prehistoric people of the Tarim Basin whose naturally preserved human remains, desiccated by the desert, suggested to many archaeologists that they were descended from Indo-Europeans who had migrated to the region from somewhere farther west before about 2000 B.C.

But the latest research shows that instead, they were a genetically isolated group seemingly unrelated to any neighboring peoples.

Related: The 25 most mysterious archaeological finds on Earth

"They've been so enigmatic," said study co-author Christina Warinner, an anthropologist at Harvard University in Massachusetts and the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany. "Ever since they were found almost by accident, they have raised so many questions, because so many aspects of them are either unique, puzzling or contradictory."

The latest discoveries present almost as many new questions as they answer about the Tarim people, Warinner told Live Science.

"It turns out, some of the leading ideas were incorrect, and so now we've got to start looking in a completely different direction," she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Desert mummies

European explorers found the first Tarim mummies in the deserts of what's now western China in the early 20th century. Recent research has focused on the mummies from the Xiaohe tomb complex on the eastern edge of the Taklamakan Desert.

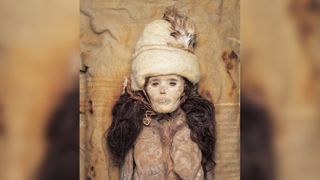

The naturally mummified remains, desiccated by the desert, were thought by some anthropologists to have non-Asian facial features, and some seemed to have red or fair hair. They were also dressed in clothes of wool, felt and leather that were unusual for the region.

The Tarim culture was also distinctive. The people often buried their dead in boat-shaped wooden coffins and marked the burials with upright poles and grave markers shaped like oars. Some people were buried with pieces of cheese around their necks — possibly as food for an afterlife.

These details suggested to some archaeologists that the Tarim people didn't originate in the region but rather were descendants of Indo-European people who had migrated there from somewhere else — perhaps southern Siberia or the mountains of Central Asia. Some scientists speculated that the Tarim people spoke an early form of Tocharian, an extinct Indo-European language spoken in the northern part of the region after A.D. 400.

Related: Image gallery: Faces of Egyptian mummies revealed

But the new study indicates that those assumptions were incorrect. DNA extracted from the teeth of 13 of the oldest mummies buried at Xiaohe about 4,000 years ago shows that there was no genetic mixing with neighboring people, said co-author Choongwon Jeong, a population geneticist at Seoul National University in South Korea.

Instead, it now seems the Tarim people descended entirely from Ancient North Eurasians (ANE), a once-widespread Pleistocene population that had mostly disappeared about 10,000 years ago, after the end of the last ice age.

ANE genetics now survive only fractionally in the genomes of some present-day populations, particularly among Indigenous people in Siberia and the Americas, the researchers wrote.

Ancient crossroads

The study also compares the DNA of the Tarim mummies to that of desert mummies of about the same age discovered in the Dzungarian region in the north of Xinjiang, on the far side of the Tianshan mountain range that divides the region.

It turned out that the ancient Dzungarian people, unlike the Tarim people roughly 500 miles (800 km) to the south, descended from both the Indigenous ANE and pastoralist herders from the Altai-Sayan mountains of southern Siberia called the Afanasievo, who had strong genetic links to the early Indo-European Yamnaya people of southern Russia, the researchers wrote.

It was likely migrating Afanasievo herders had mixed with local hunter-gatherers in Dzungaria, while the Tarim people retained their original ANE ancestry, Jeong told Live Science in an email.

However, it's not known why the Tarim people remained genetically isolated while the Dzungarians did not.

"We speculate that the harsh environment of the Tarim Basin may have formed a barrier to gene flow, but we cannot be certain on this point at the moment," Jeong said.

The desert environment doesn't seem to have cut the Tarim people off from cultural exchanges with many different peoples, however. The Tarim Basin in the Bronze Age was already a crossroads of cultural exchange between the East and the West and would remain so for thousands of years.

"The Tarim people were genetically isolated from their neighbors while culturally extremely well connected," Jeong said.

Among other things, they had adopted the foreign practices of herding cattle, goats and sheep, and of farming wheat, barley and millet, he said.

"Probably such cultural elements were more productive in their local environment than hunting, gathering and fishing," Jeong said. "Our findings provide a strong case study showing that genes and cultural elements do not necessarily move together."

Warinner said the ancient Tarim communities were sustained by ancient rivers that brought water to parts of the region while leaving the rest of it desert. "It was like a river oasis," she said.

Parts of ancient fishing nets have been found at Tarim archaeological sites, and the practice of burying their dead in boat-shaped coffins with oars may have developed from their reliance on the rivers, she said.

The rivers were fed by seasonal snow melt in the surrounding mountains, and often changed course when there had been an especially heavy snowfall over winter. When that happened, the ancient villages were effectively stranded far from water, and that may have contributed to the end of the Tarim Basin culture, she said. Today, the region is mostly desert.

The study was published Oct. 27 in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.