Chain of Alaskan islands might really be one monster volcano

A giant caldera may be lurking underwater in the Aleutians.

How does a giant volcano hide in plain sight? It disguises itself as a group of smaller volcanic islands. At least, that may be the case for some of Alaska's Aleutian Islands.

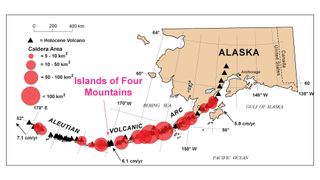

A tight cluster of six volcanic islands located near the center of the chain — the stratovolcanoes Carlisle, Cleveland, Herbert, Kagamil, Tana and Uliag — are actually interconnected vents for a much bigger volcano lurking underwater, scientists recently proposed. If so, it would be the first entirely submerged volcano in the Aleutians, the scientists said in a statement.

These six stratovolcanoes are collectively known as the Islands of the Four Mountains. But they might also be connected as part of a caldera, a massive, bowl-shaped volcanic depression that can contain multiple vents, according to findings that will be presented virtually on Monday (Dec. 7) at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

Related: Photos: Hawaii's new underwater volcano

The scientists analyzed seismic activity, gas emissions, gravity measurements and geochemistry in the region surrounding the six islands. Their findings hinted that activity in the stratovolcanoes could be traced to a much bigger source — "a large, previously unrecognized caldera that is largely hidden by recent deposits and the surrounding ocean," the researchers reported.

"Everything we look at lines up with a caldera in this region," study co-author Diana Roman, a volcanologist and a staff scientist with Carnegie Institution for Science in Washington, D.C., said in the statement.

The Aleutian Islands is an archipelago with dozens of islands, containing 40 active and 17 inactive volcanoes. It stretches more than 1,860 miles (3,000 kilometers) between Alaska and Russia, forming the southern boundary of the Bering Sea, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most stratovolcanoes, such as the Aleutians' Islands of the Four Mountains, are cone-shaped structures with steep sides that build up over time from accumulated flows of lava, ash and rock. These volcanoes draw their eruptive power from moderately-sized magma reservoirs underground.

Calderas, by comparison, are shaped by gargantuan magma reserves in Earth's crust, and they form when the pressure of the reservoir explodes out of the crust in a single massive eruption. The volcano then collapses into the depleted magma chamber, leaving a depression behind.

Some calderas measure up to 62 miles (100 km) in diameter, and the volcanic events that cause them release far more ash and lava than stratovolcano eruptions, according to National Geographic. Three overlapping calderas in Yellowstone National Park are remnants of eruptions that exploded 2.1 million, 1.3 million and 640,000 years ago, and they extend for 45 miles (72 km) atop a supervolcano. The oldest of those eruptions blanketed 5,790 square miles (15,000 square km) with ash, according to the National Parks Service.

The Aleutian volcano Mount Cleveland is one of the most active volcanoes in North America, and the presence of a massive underwater caldera in the Aleutians could explain why Cleveland erupts so often, lead study author John Power, a researcher with the U.S. Geological Survey at the Alaska Volcano Observatory, said in the statement.

A caldera that encompasses six volcanic islands would likely represent a supervolcano comparable to the monster volcano in Yellowstone — but more evidence would be required to confirm that the Islands of the Four Mountains are connected, Roman said.

"Our hope is to return to the Islands of Four Mountains and look more closely at the seafloor, study the volcanic rocks in greater detail, collect more seismic and gravity data, and sample many more of the geothermal areas," she said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.