Oldest-known shark attack discovered in 3,000-year-old skeleton with 800 injuries

Parts of his body were missing when he was buried.

About 3,000 years ago, a shark fatally mauled a man in waters near western Japan. The encounter left a map of horrific scars spread across the man's skeleton, and parts of his body were never recovered.

Analysis of the person's bones, which were excavated from a communal burial ground at the Tsukumo archaeological site in Okayama prefecture, documented 790 traumatic injuries, such as cuts, punctures, fractures from blunt force and deep, crisscrossing gouges with "sharp, V-shaped edges," the researchers wrote in a new study. Such wounds match those left by sharks, making this the world’s oldest recorded instance of a shark attack on a human — about 1,000 years older than the previous record-holder.

Related: In photos: Seeing sharks up close

"This find not only provides a new perspective on ancient Japan, but is also a rare example of archaeologists being able to reconstruct a dramatic episode in the life of a prehistoric community," study co-author Mark Hudson, an archaeologist with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena, Germany, said in a statement.

The man's injuries were so numerous that he probably didn't survive, and he would have died from blood loss and shock, the study authors wrote. He likely was alive when attacked, as the distribution of skeletal damage differed from damage patterns left by sharks on scavenged corpses. The widespread trauma to the skeleton also suggests "that the victim remained in the sea for some period of time sufficient to allow the shark to feed on the body after death," the scientists reported in the August 2021 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Torn apart

Construction workers uncovered the Tsukumo site in 1860, and the first archaeological excavations took place in 1915. Since then, archaeologists have found more than 170 human remains buried there. But only one skeleton, an adult male known as Tsukumo No. 24, had such serious and extensive injuries. The remains of the man, who died between 1370 B.C. and 1010 B.C., showed traumatic lesions scarring the majority of his skeleton, with most of the damage on his pelvis, left leg, shoulders and arms. He was also missing his left hand and right leg, and his left leg had been arranged upside-down in the grave, according to the study.

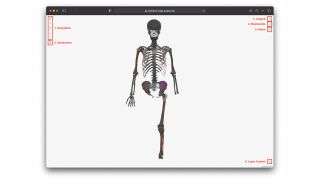

The authors scanned the bones with X-ray computed tomography (CT) and built a 3D model of Tsukumo No. 24 so they could visualize and map his injuries. Nearly all of the ribs had been bitten and fractured, and "the chest cavity and abdomen may have been eviscerated," the scientists wrote. Wounds were heavily concentrated around the left hip and leg, hinting that the man may have lost his left hand while trying to defend that part of his body. Long bones in the arms and legs showed bites from numerous directions, suggesting that the shark continued circling and tearing at the corpse after the man was dead.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What type of shark attacked him so long ago? Tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) and great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) are the most likely candidates, as both are commonly found in Japan's Seto Inland Sea near the site where the body was buried; both species have also been known to attack humans, according to the study. However, such attacks are rare, and most sharks don't attack people without provocation, the researchers added.

"Humans have a long, shared history with sharks," the scientists reported. "This is one of the relatively rare instances when humans were on their menu, and not the reverse."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.