Biggest prehistoric monument in UK discovered just a stone's throw away from Stonehenge

Archaeologists have discovered what may be the largest prehistoric monument in the entire United Kingdom, and it's just a stone's throw away from Stonehenge, a new study finds.

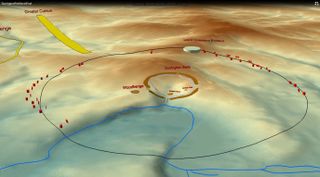

By using a combination of remote sensing and hands-on excavation work, the team found evidence for at least 20 giant holes dating to the Neolithic, about 4,500 years ago. Each hole is massive, measuring at least 32 feet (10 meters) in diameter and at least 16 feet (5 m) deep.

Related: In photos: A walk through Stonehenge

These holes form a circle larger than 1.2 miles (2 kilometers) across, which covers an area larger than 1.2 square miles (3.1 square km). At the center of this giant circle is one of the largest henges in the U.K., known as Durrington Walls — which is 1,640 feet (500 m) in diameter — as well as the smaller Woodhenge, which measures just 360 feet (110 meters) across. (A henge is a circular, prehistoric monument made with stone or wooden markers.)

"We continually get to this point of thinking that in the past they weren't that developed or sophisticated people," study co-researcher Richard Bates, a professor in the School of Earth & Environmental Sciences at the University of St Andrews in Scotland, told Live Science. "And, yet again, this [finding] has proven that in the past, our ancestors were."

Bates and his colleagues, who are part of the Stonehenge Hidden Landscapes Project, first realized last summer that the giant holes they were finding during their archaeological surveys were not naturally occurring dewponds (shallow, artificial ponds that provided cattle with drinking water), but rather human-dug shafts laid out in a circular pattern. "We gradually became convinced we were not looking at natural things," Bates said. "These had to be made by humans."

Radiocarbon dating of shell and bone fragments found in sediment cores from these holes indicate that Neolithic people dug the shafts around the same time that Durrington Walls was built, or about from 2800 B.C to 2100 B.C. This timing may not be coincidental, but a clue; perhaps these holes served as a boundary to a sacred area within the circle, archaeologists said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One idea is that the different levels of the different enclosures marked which levels of society were allowed within, Bates said. "Whether this line of pits marks a zone, whereby only a certain [type of] people could go beyond it, that's one of the thoughts," he said. "If there was lots of feasting, sacrificial or otherwise, made within Durrington, maybe this represents as far as all the cattle could go before the priests."

Image gallery

Moreover, the newfound henge seems to mark the boundary for an earlier prehistoric sacred area known as the Larkhill Causewayed Enclosure, a site built more than 1,500 years earlier than the henge at Durrington. This enclosure, as well as the newfound pits, are all about 2,834 feet (864 m) away from Durrington Walls, the archaeologists noted. Perhaps these holes signified a cosmological link between these pits and Durrington Walls, the researchers said.

Related: Image gallery: Stunning summer solstice photos

Neolithic people may have purposefully designed these pits to hold water during the wet season, but more research is needed to confirm that idea, Bates noted.

Although the circle of shafts at Durrington are one of a kind — there aren't any comparable prehistoric structures like it elsewhere — it's not surprising that Neolithic people invested time and energy digging them, the researchers said. During the Neolithic, Britain saw its first farmers, who developed detailed and sometimes large structures — such as Stonehenge, whose stones were erected about 2,500 years ago — to house their ritual ceremonies.

It's unclear exactly how Neolithic people determined where to dig the holes, but maybe they used a tally or counting system to count their paces over long distances, as some of the holes are somewhat evenly spaced, the researchers said.

In addition, "one pit may provide evidence for [getting dug again], suggesting that some of these features could have been maintained through to the middle Bronze Age," the researchers wrote in the study, published online June 21 in the journal Internet Archaeology.

"As the place where the builders of Stonehenge lived and feasted, Durrington Walls is key to unlocking the story of the wider Stonehenge landscape," Nick Snashall, an archaeologist with the National Trust for the Stonehenge and Avebury World Heritage Site, said in a statement, "This astonishing discovery offers us new insights into the lives and beliefs of our Neolithic ancestors."

- In Photos: Ireland's Newgrange Passage Tomb and Henge

- 5 strange theories about Stonehenge

- Image gallery: Digging up a tomb at the Swedish Stonehenge

Originally published on Live Science.

<a href="https://www.livescience.com/download-your-favorite-magazines.html" data-link-merchant="livescience.com"">OFFER: Save 45% on 'How It Works' 'All About Space' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of<a href="https://www.livescience.com/download-your-favorite-magazines.html" data-link-merchant="livescience.com"" data-link-merchant="livescience.com""> our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.