Hidden 'Jurassic World' of Volcanoes Uncovered in Australia

Dating to the days of the dinosaurs, these volcanoes have slumbered underground for millions of years.

A field of volcanoes in Australia dating to the days of the dinosaurs has slumbered deep underground for millions of years, and scientists recently developed a snapshot of this long-hidden volcanic network.

The volcanoes — about 100 of them — formed between 180 million and 160 million years ago and covered an area of nearly 2,900 square miles (7,500 square kilometers), researchers reported in a new study.

This formerly lava-spewing Jurassic landscape was buried under hundreds of feet of rock in Australia's Cooper and Eromanga basins, a desert region in the central part of the continent known for its rich reserves of oil and natural gas.

Related: The 11 Biggest Volcanic Eruptions in History

More than 30 years ago, drilling in the Cooper and Eromanga basins turned up the first evidence of igneous rocks — rocks formed by cooled magma — dating to the Jurassic period, around 199.6 million to 145.5 million years ago. During the decades of fossil fuel extraction that followed, experts gathered a "massive amount of data from underneath the ground," said study co-author Simon Holford, an associate professor of petroleum geoscience at the University of Adelaide's Australian School of Petroleum.

But it was only recently that scientists looked at this data to find out where the rocks may have been coming from, Holford told Live Science in an email.

"Despite all this data, the volcanoes have never been properly understood — until now," Holford said. "So, we are in a privileged position to reconstruct ancient geological processes."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

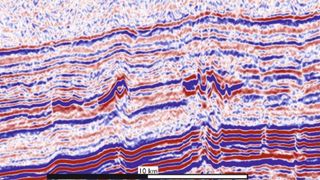

Subsurface imaging technology, such as seismic reflection — the use of seismic waves to evaluate physical properties in layers of rock — revealed chambers of magma that once fueled the Jurassic volcanoes; channels of ancient lava flows; and volcanic craters. The scientists have now named the site the Warnie Volcanic Province, after the nearby Warnie East 1 exploration well, according to the study.

Active no more

During the Jurassic period, the volcanic network would have been highly active, with cracks and craters belching lava and ash. Today, those volcanoes are quiet, though southeastern Australia experienced volcanic activity as recently as 5,000 years ago, Holford said.

"The town of Mount Gambier in South Australia is built on a Holocene volcano, which is quite similar in terms of size and morphology to the volcanoes we've uncovered," Holford said. (The Holocene began 12,000 to 11,500 years ago and continues to the present.)

What buried the ancient volcanoes? It wasn't a single cataclysmic event; rather, the volcanoes were submerged slowly under layers of sediment over millions of years, Holford said. In fact, all of central Australia has been slowly sinking for around 160 million years, though scientists aren't entirely sure why.

"Over time, the subsidence has allowed for the accumulation of hundreds of meters of sedimentary rocks — mostly shales and sandstones — which have buried and preserved this ancient landscape," Holford said.

What's more, other "volcanic provinces" may hide under Australia and in other parts of the world, the study authors reported.

"Many people have a tendency to focus on what we can see, but we need to take into account things we can't see that are buried underneath the ground," Holford said.

The findings were published online Aug. 13 in the journal Gondwana Research.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular