Short Legs Made Human Predecessors Better Fighters

Our ape-like predecessors kept their stout figures for 2 million years because having short legs ironically gave them the upper-hand in male-male combat for access to mates, finds a new study.

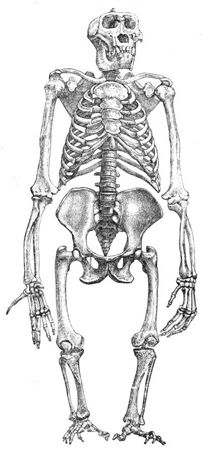

Living from 4 million to 2 million years ago, early hominins in the genus Australopithecus are considered immediate predecessors of the human genus Homo, and had heights of around 3 feet 9 inches for females and 4 feet 6 inches for males.

Until now, the squat physiques of Australopiths and other human predecessors were considered an adaptation for climbing in tree canopies. Like surfing or any other sport that requires balance, having a lower center of mass boosts stability and, in turn, success at the activity.

"The old argument was that [apes] retained short legs to help them climb trees that still were an important part of their habitat," said the study author David Carrier, a biologist at the University of Utah. "My argument is that they retained short legs because short legs helped them fight."

Body measurements

Carrier compared hind-limb lengths and indicators of aggression of human aborigines with those of eight additional primate species, including gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans, black gibbons, siamang gibbons, olive baboons and dwarf guenon monkeys. The Australian aborigines were chosen because they are a relatively natural population.

As indicators of aggression, Carrier looked at the weight difference between males and females and the male-female difference in length of canine teeth, which are used for biting during battle. Studies have shown greater aggression in primate species in which males tipped the scales relative to females.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Primates with the stoutest figures also ranked high on both aggression measurements. For instance, the gibbons boasted longer legs than other apes and also ranked low on the aggression scale. In contrast, male gorillas, which are more than double the size of females, were stout.

The lengthy legs didn't keep gibbons away from canopies either. "Gibbons are the best acrobats in the animal kingdom. There are no other animals that can move through the canopy the way a gibbon can," Carrier told LiveScience. "And they contrast male gorillas, which hardly ever climb. When they do climb they stay close to the trunk, they spend most of the time on the ground."

Carrier noted exceptions to the short-limb rule. While bonobos have shorter legs than chimps, they are less aggressive.

Human aggression

Even though Australopiths walked upright on the ground, they retained short legs for 2 million years for the same reason squatness helped out other great apes--for male-male combat. With the advantage in combat, short-legged primates would likely be victorious and gain access to females. That meant passing their genetic traits, like shortness, to offspring.

Just because humans have long legs doesn't make us less aggressive. Rather, the longer legs are a product of humans' specialization for distance running. The tendency toward aggression in ape ancestors could have carried through evolutionary history to become a characteristic of modern humans, Carrier suggests. He says that's surprising since humans are considered such advanced animals.

"To some extent, our evolutionary past may help us to understand the circumstances in which humans behave violently," Carrier said. "There are a number of independent lines of evidence suggesting that much of human violence is related to male-male competition, and this study is consistent with that."

The study is published in the March issue of the journal Evolution.

Jeanna served as editor-in-chief of Live Science. Previously, she was an assistant editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Jeanna has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland, and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Most Popular