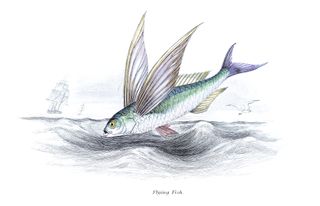

Flying fish: Real fish, but not really flying

Flying fish erupt out of the ocean and can be airborne for up to 45 seconds, but they do not actually fly.

In warm ocean waters around the world, you may see a strange sight: A fish leaping from the water and soaring dozens of meters before returning to the ocean's depths. Early Mediterranean sailors thought these flying fish returned to the shore at night to sleep, and therefore called this family of marine fish Exocoetidae (in Latin, "ex-" means "out of" and "koitos" means bed), according to Steve N.G. Howell's book "The Amazing World of Flyingfish" (Princeton University Press, 2014).

What are flying fish?

There are about 40 species of flying fish, all of which tend to be cigar-shaped with long, wide pectoral fins on either side of their bodies. Broadly speaking, there are two categories of flying fish: "two-wingers," whose two large pectoral fins comprise most of the flying "lift" surface; and "four-wingers," which also have two enlarged pelvic fins in addition to the two long pectoral fins. All flying fish have an asymmetrical, vertically forked tail (a shape known as hypocercal), with vertebrae extending into the longer, bottom lobe of the fork, making it look sort of like a boat’s rudder.

These unusual fish range in length from about 6 to 20 inches (15 to 50 centimeters), or about one or two brick lengths. Juvenile fish will begin "flying" once they reach about 2 inches (5 cm) in length, according to biologist John Davenport's 1994 review on flying fish published in the journal Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries. Davenport proposes that these species of fish evolved the ability to "fly" as a way to evade speed-swimmer predators such as the dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus).

Related: Flying fish evolved to escape prehistoric predators

The fish's eyes, particularly the cornea (the pyramid-shaped barrier that protects their eyes), have evolved to enable the fish to see underwater as well as in the air, according to a 1967 study published in the journal Nature.

Flying fish aren't picky eaters but mainly dine on small crustaceans and fish, according to a report by the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency.

Flying fish don't actually fly; they glide

Flying fish soar at very high speeds above the water. The fish are so fast, that for decades, biologists couldn't tell for sure if the fish were propelling themselves by flapping their pectoral fins and flying like a bird, or if the fish were using some unique method of propulsion. It wasn't until 1941 that scientists published high-speed photographs of flying fish in action in the journal Zoologica. The photos showed that flying fish leap out of the water and glide, before propelling themselves back into the air.

Flying fish swim towards the surface at speeds of about 3 feet (1 meter) per second (which is 20-30 times their body length per second), beating their tail furiously and holding their pectoral fins tightly against their body. When they erupt out of the water, they spread their enlarged fins and glide.

Related: How flying fish took flight? Fossils may tell us

The longest flying fish glide ever recorded was a fish that soared for 45 seconds at an estimated speed of 30 km/h (19 mph), according to Guinness World Records. The record flight was caught on camera in 2008 by a Japanese film crew traveling on a ferry in Kagoshima, Japan. The farthest recorded flight distance of a flying fish is about 1,312 feet (400 m), according to Davenport's 1994 review.

Flying fish can gain heights of up to 26 feet (8 m) above the surface, and can perform consecutive glides, according to biologist Frank Fish's 1990 review published in the Journal of Zoology. When the fish splashes back down into the water at the end of a glide, it will immediately start swimming super fast, picking up speed to produce enough thrust to lift out of the water again. The fish may have up to 12 successive glides, Fish wrote.

Davenport and other fish experts suspect that flying fish would be unlikely to fly at temperatures lower than 68 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius), as cooler temperatures tend to impede the muscle function necessary to achieve the speeds necessary for launching out of the water.

Fishing for flying fish

Flying fish are not considered endangered or threatened, and are categorized as a species of least concern by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources.

In recent decades, the fourwing flying fish (Hirundichthys affinis) has been at the center of an international dispute between the neighboring Caribbean island nations of Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago. The fish is a commercially-targeted species in both countries. Barbados has even adopted the slogan "Land of the Flying Fish," in recognition of the fish's long cultural and economic importance.

But a change in the fish's migratory patterns, possibly due to global warming, has seen them swimming more frequently in the waters surrounding Trinidad and Tobago, and commercial fishers from Barbados have followed. Tobagonian fishers accuse Barbadians of overfishing in water that doesn't belong Barbados, but "as a traditional food source for Barbados, Barbados fishermen believe they have the right to catch the fish wherever the fish might be," researchers wrote in a summary of the conflict published in 2007 in the journal Marine Policy.

In 2006, an arbitral case to settle the fishery dispute established each country's maritime borders and was considered a victory by both nations. Nonetheless, the conflict seems to persist, and the authors of the 2007 summary suggest that a negotiated agreement involving a limited access program and fishing quotas would be the best way to manage the fishery in the future.

Additional resources:

- Watch how flying fish try (unsuccessfully) to evade fast-swimming predators in this video from BBC Earth.

- Here's how to make the national flying-fish dish of Barbados, according to National Foods of the World.

- Read about flying fish in the Gulf of Mexico from Loyola University New Orleans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sarah Wild is a science journalist and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com. She is the author of "Searching African Skies: The Square Kilometre Array", "Innovation: Shaping South Africa through Science" and "South Africa's Quest to Hear the Songs of the Stars." Wild was the winner of the Siemens pan-African Profile Awards for science journalism in 2013 and received the Dow Technology and Innovation Reporting award in 2015.