9 epic space discoveries you may have missed in 2020

Radio mysteries and X-ray bubbles and alien worlds, oh my!

Medical discoveries dominated the news in 2020, but even under pandemic conditions, astronomers kept up their work. They hunted through radio waves for mystery signals, discovered new galaxies and even figured out which alien star systems might be able to detect Earth.

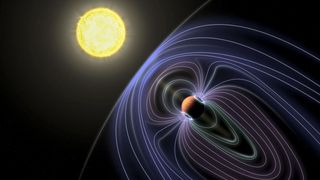

Radio emissions from an alien world

Planets in the solar system emit radio waves, especially Jupiter with its intense magnetic fields. But no one had ever detected radio waves coming from a planet beyond the solar system until this year, when researchers picked up a signal from a gas giant in the Tau Boötes system, just 51 light years from Earth. That signal could help them learn more about that exoplanet's magnetic field, which could offer clues to what's going on in its atmosphere.

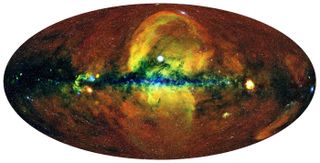

X-ray blobs bursting from the Milky Way

Millions of years ago, an explosion in the center of the Milky Way blasted energized material above and below the galactic disk. That material is still visible, glowing in the gamma ray spectrum in two clumps discovered in 2010, known as the Fermi Bubbles. In 2020, researchers found another pair of blobs in the same region, visible in the X-ray spectrum. Likely related to the Fermi bubbles, these dim, gargantuan features of the Milky Way tower over the 25,000-light year Fermi Bubbles, to a width of 45,000 light-years end to end. Researchers named them the "eROSITA bubbles."

A long-lost rocket booster

Earth acquired a new "minimoon" in 2020, one of several objects that the planet encounters in space from time to time that end up in orbit around our planet. But closer examination by amateur and professional space watchers revealed this minimoon wasn't a natural object at all, but rather a rocket booster NASA launched in the 1960s.

Ghostly radio circles

Scientists frequently find things in space that look like fuzzy blobs, but the newfound odd radio circles (ORCs), discovered in 2019 and reported in 2020, are special. The round blobs, visible in radio telescope data, don't look like any known object. They're not supernova remnants, or optical effects known as Einstein rings. Some scientists have even suggested they may be the throats of wormholes. But no one really knows what these newly discovered things are.

A million new galaxies

A radio telescope in the Australian outback mapped 83% of the observable universe over the course of 300 hours of observations. And it revealed a big haul of data: 3 million galaxies, a full million of which had never been seen before. The Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) relies on 36 antennas to record the sky, but this was the first time that all 36 had been used at once for a single project.

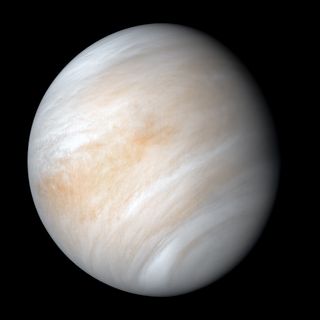

A hint of life on Venus?

Venus may be the most inhospitable place in the solar system, with roiling acid clouds and hellish temperatures. That's why astronomers getting ready to look for phosphine, a smelly gas thought to be a possible signature of life on alien planets, trained their phosphine-hunting telescope on Venus first: They wanted a reference image from a surely-dead world. But in a shocking twist, they found the compound in Venus's clouds.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Other researchers have urged caution before suggesting there's really life on Venus, however.

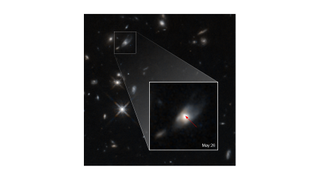

A newborn magnetar

On Nov. 12, researchers detected a bright kilonova, a light show from the aftermath of two neutron stars merging together. Kilonovas are rare in space, but researchers have seen them before. This one was special though: Weird signals in the kilonova light indicated the presence of something new. Researchers studying the event offered a few possibilities, but said the most likely is a newborn magnetar: a huge, super-magnetic neutron star that formed during the collision.

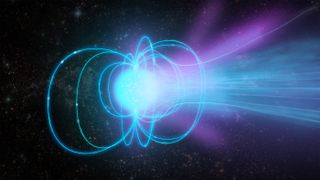

The source of a fast radio burst

Magnetars may also be responsible for the brightest flashes of light in space. These "fast radio bursts" have mystified astronomers for years, packing the energy the sun emits in days into just milliseconds. Most seem to come from far beyond the Milky Way, but in 2020 researchers reported an FRB originating in our home galaxy, just 30,000 light-years from Earth. And this one had a known point of origin: a magnetar. Does that mean all such bursts come from magnetars? No one is sure.

The aliens that might see us

Astronomers detect alien planets by watching them pass between Earth and their stars. Someday they might even study their atmospheres by watching how the starlight glints through them. But that only works for planets with orbits that align to put them between Earth and their home star. Planets that don't line up that way are mostly invisible to current telescope technology.

In 2020, researchers asked which star systems have vantage points on Earth that would let them see our little planet with its atmosphere pulsing with signs of life. They identified 1,004 star systems capable of seeing Earth within 326 light years. One star just 12 light years from Earth has known exoplanets and will have the proper vantage point to see Earth when it moves into position in 2044.

Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular