Massive DDT dumping ground found off the Los Angeles coast is bigger than anyone thought

A survey recently mapped over 27,000 barrels of industrial waste and DDT.

The sea bottom near southern California has been hiding a very dirty secret: decades of discarded chemicals in thousands of barrels. And the toxic debris field is even bigger than anyone expected, containing at least 27,000 drums of DDT and industrial waste, scientists recently discovered.

High concentrations of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, an insecticide that was widely used for pest control during the 1940s and 1950s) were previously detected in ocean sediments between the Los Angeles coast and Catalina Island, in 2011 and 2013. At the time, scientists who searched the seafloor in the area identified 60 barrels (possibly containing DDT or other waste) and found DDT contamination in sediments, but the full extent of the area's contamination was unknown.

Now, a research expedition presents a clearer picture of the deep-sea dump site. Their findings reveal a stretch of ocean bottom studded with at least 27,000 industrial waste barrels — and possibly as many as 100,000, researchers with Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California said in a statement.

Related: 10 of the most polluted places on Earth

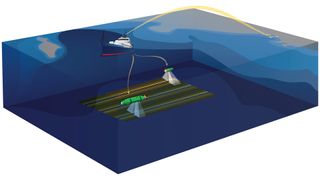

From March 10 to March 24, a team of 31 experts onboard the Scripps research vehicle Sally Ride created high-resolution acoustic maps of the seafloor at the San Pedro Basin, covering 36,000 acres (146 square kilometers) from 12 miles (19 kilometers) off the coast of southern California to 8 miles (13 km) from Catalina Island. Two underwater autonomous vehicles (AUVs) named REMUS 6000 and Bluefin swam through depths up to 3,000 feet (900 meters) below sea level, using sonar to pinpoint the locations of the barrels.

These containers were quite small — less than 3 feet (1 m) tall — and those that were buried looked even smaller in the sonar scans, expedition member Sophia Merrifield, a Scripps oceanographer and data scientist, said at a virtual news conference on April 27. The researchers therefore had to develop algorithms that would automate the process for identifying and counting such tiny objects, Merrifield explained.

"We needed to be able to pump hundreds of gigs [gigabytes] through an algorithm that would detect these very small, very bright targets," she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Images of the 60 sunken barrels spotted in 2011 and 2013 helped the scientists calibrate their algorithms. The result categorized not only an object's location but also its size and brightness, "so that we can do further pattern analysis and classification of the types of targets," Merrifield said.

From the AUV scans and data analysis, the expedition scientists discovered that more than 90% of the survey area contained some debris, Eric Terrill, chief scientist of the expedition and director of the Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps, said at the news conference. Researchers found 100,000 pieces of human-made debris and identified the subset that were likely barrels holding DDT and other types of industrial waste, Terrill said.

"Irreversible damage"

This accumulation of seafloor dumping didn't happen overnight. While Los Angeles today is mostly associated with Hollywood and moviemaking, oil and gas were once thriving industries in the area, and much of the waste from extraction and processing wound up in the ocean, Terrill said at the press event.

"The dumping of industrial rate waste in the ocean actually began in the '30s and continued all the way into the early '70s," Terrill said.

Companies also dumped byproduct waste from agricultural DDT manufacturing in the sea, and in 1985 the Los Angeles Water Quality Control Board released a troubling report describing "decades of systematic neglect" in official oversight of toxic waste disposal, "with the result being irreversible damage to the marine environment," the Los Angeles Times reported that year.

According to estimates, companies dumped between 386 and 772 tons (350 and 700 metric tons) of waste at offshore locations in the San Pedro Basin over nearly four decades, Terrill said. But it was unknown how extensive the dumping was, where exactly it happened, and if the containers holding the waste were leaking (and how much).

A nearby location in the Palos Verdes Shelf is already recognized as highly contaminated with DDT and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls, another toxic industrial compound) and is designated as a Superfund site — a location so permeated with hazardous waste that it has been targeted by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for cleanup, Terrill said.

Related: Sea science: 7 bizarre facts about the ocean

Vital clues came to light in 2011 and 2013, when David Valentine, a professor of Earth science and biology at the University of California Santa Barbara's Marine Institute captured remote camera images of 60 industrial waste barrels on the seafloor, describing the toxic mess in a study published in 2019 in the journal Environmental Science and Technology.

Then, in October 2020, investigative reporting by the L.A. Times dug up damning details about DDT dumping. Shipping logs from the Montrose Chemical Corporation of California — the largest manufacturer of DDT in the U.S., based in Los Angeles from 1947 to 1982 — noted that thousands of barrels containing DDT were transported monthly and discarded in the deep sea near Catalina. In later years, crews began dumping the barrels closer to the California coast.

They also took other measures to speed up the work. "When the barrels were too buoyant to sink on their own, one report said, the crews simply punctured them," the L.A. Times reported.

While the research team doesn't yet know how many of the 27,000 newly-described barrels hold DDT, the survey offers a starting point for investigating the containers' environmental impact. The team's discoveries have already prompted California Senator Dianne Feinstein to request that the EPA "prioritize urgent and meaningful action to remediate this serious threat to human and environmental health," in a letter to the agency penned on March 12.

The scientists plan to analyze the data from the R/V Sally Ride expedition for a future peer-reviewed study, but releasing these initial findings (first in March, then in more detail on April 26) calls attention to the scope of the dump site and the threats it may pose to ocean ecosystems and marine life, the scientists said.

"Putting this out now as a way to get information to policymakers and for other efforts," Merrifield said.

"We are hopeful the data will inform the development of strategies to address potential impacts from the dumping," Terrill added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular