Scientists grew human tear ducts in a lab and taught them to cry

The glands had no openings so they swelled up like "balloons."

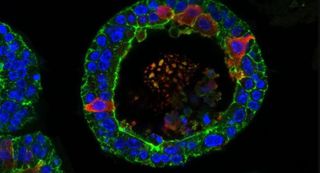

Disembodied human tear glands, grown in petri dishes in a laboratory in the Netherlands, have the ability to cry — and the scientists who created them have already grafted them into the eyes of living mice.

The series of experiments, detailed in a new study published online March 16 in the journal Cell Stem Cell, could represent a major step forward in the science of treating dry eye — a condition that impacts about 5% of adults worldwide and can lead to blindness in severe cases.

Petri-dish body parts have become more commonplace in laboratory experiments, but they're often much smaller and simpler than their natural counterparts. "Minibrains," for example, are smooth, pea-size, unconscious organoids that only loosely resemble the original organs, Live Science has reported. The petri-dish tear glands, however, were pretty close to the real thing, according to Marie Bannier-Hélaouët, a co-lead author of the study and researcher at the Hubrecht Institute in Utrecht, Netherlands.

Related: 11 body parts grown in the lab

Human tear glands, Bannier-Hélaouët told Live Science, have two components: acinar cells and ductal cells.

"Both can make tears, but the ductal cells have an additional function: They act like a canal to bring the tears to the eye surface. The [lab-made] organoids look like this canal," she said. "The difference is that, as in the dish there is no eye to bring the tears to, the organoids look like a canal with dead ends. They are balloons."

Those balloons are similar in size to what you'd find in a human, growing up to about one-50th of an inch (half a millimeter) wide.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers divided the study into three experiments. In the first they grew human tear glands in petri dishes and got them to produce tears.

Growing the organoids was one thing, Bannier-Hélaouët said. Getting them to cry was another, since that involves brain chemicals called neurotransmitters.

"Working out the perfect cocktail [of neurotransmitters] to make the organoids cry was the most challenging part. It took me about three or four months and about seven to 10 trials," she said. "What is striking is that this final cocktail contains very few ingredients. One of them is simply an antioxidant molecule."

Once the cocktail had been perfected, the researchers observed the glands puffing up with tears that had nowhere to go.

Next, they implanted some of those lab-made glands into the tear ducts of living mice. They found that the implanted human cells could still produce tears, but they didn't release them into the ducts the way normal glands would. Eventually, she said, it will be important to figure out how to make the glands act normally in living tear ducts.

"We already have ideas on how to do this," Bannier-Hélaouët said.

In the final part of the study, the researchers focused on pinpointing the origin of a form of chronic dry eye known as Sjögren's syndrome, an autoimmune condition that also causes dry mouth.

In petri dishes, the researchers grew mouse tear glands that had been modified with gene-editing technology to not express a gene known as Pax6. Researchers had already established that people with dry eye often lack Pax6 in their eye tissue and that the gene plays an important role in eye development. Their experiment showed that the mouse organoids modified to lack Pax6 produced fewer tears, bolstering the idea that the gene is linked to the medical problem.

Originally published on Live Science.