500 million-year-old creature with mashup of bizarre features could be arthropod 'missing link'

A shrimp-like animal that paddled around the ocean hundreds of millions of years ago peered through the water with five eyes mounted on stalks. But that wasn't even the weirdest thing about it, researchers recently discovered.

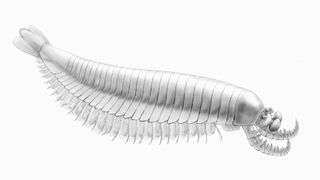

Those stalks supported compound eyes, mounted on a semi-circular fused head shield; the tiny sea beast also had an articulated upper body, 15 jointed and spine-tipped limbs, and large, upward-curving "arms" that were likely used to snap up prey.

Some of these features are known separately from fossils of other ancient arthropods, the invertebrate group with exoskeletons, segmented bodies and jointed legs. But this oddball creature is also a chimera — possessing features from multiple animals.

Related: Photos: 'Naked' ancient worm hunted with spiny arms

During the Cambrian period (543 million to 490 million years ago), arthropods emerged as one of the most successful animal groups on Earth; they now represent approximately 80% of all species alive today. Arthropod fossils show that their diversity boomed during the Cambrian. But the full story of the group's early evolution is incomplete, and the discovery of this newly described species — which would have measured around 3 inches (7 centimeters) in length when alive — could help fill in some critical gaps, the researchers reported.

The study authors analyzed six fossils from the Yu'anshan Formation in southern China, where fossil deposits date to the early Cambrian, around 518 million years ago. They dubbed the strange creature Kylinxia zhangia — "kylin" is the name of a chimera from Chinese mythology; "xia" is the Chinese word for shrimp-like arthropod; and "zhangia" is a nod to Yehui Zhang, contributor of one of the specimens, according to the study.

The fossils were in excellent condition, revealing that two of the eyes at the front of the stalk cluster were twice as big as the rest. In addition to the eyes, soft tissues such the alimentary canal, digestive glands, nerve tissue and ventral cord, and even expelled gut contents were preserved in the fossils.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The Kylinxia fossils exhibit exquisite anatomical structures," said study co-author Fangchen Zhao, a professor with the Nanjing Institute of Palaeontology and Geology (NIPG) at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Nanjing, China. "For example, nervous tissue, eyes and digestive system — these are soft body parts we usually cannot see in conventional fossils," Zhao said in a statement.

"Missing link" fossil

Kylinxia's chimerical mashup of features from some of the earliest known arthropods is what really caught the scientists' attention. Its cluster of five eyestalks is also found in the ancestral arthropod Opabinia, while its grabby appendages at the front of its body resembled those of Anomalocaris, a 3-foot-long (1 meter) Cambrian marine arthropod known as the "world's first apex predator."

Though Anomalocaris is considered an ancestral arthropod, it looks very different from true arthropods that evolved later in the family tree, and Kylinxia's melange of features hinted at evolutionary connections that were previously missing.

After examining all of Kylinxia's characteristics and comparing nearly 300 other arthropod features in more than 80 taxonomic groups, the study authors concluded that Kylinxia resolved evolutionary relationships between several ancestral lineages for the arthropod group Deuteropoda, which included Anomalocaris and modern lineages.

Kylinxia's enlarged forelimbs — the feature it shared with Anomalocaris — may also have been precursors of structures that evolved in later arthropods; these structures include the mouthparts in Chelicerata arthropods like scorpions and spiders, and sensory antennae like those found in Mandibulata arthropods, the group that includes insects, crustaceans and millipedes.

"Kylinxia represents a crucial transitional fossil predicted by Darwin's evolutionary theory," lead study author Han Zeng, a NIPG assistant professor, said in the statement.

"It bridges the evolutionary gap from Anomalocaris to true arthropods and forms a key 'missing link' in the origin of arthropods, contributing strong fossil evidence for the evolutionary theory of life," Zeng said.

The findings were published online today (Nov. 4) in the journal Nature.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.