Meditation may have shaved 8 years of aging off Buddhist monk's brain

A 41-year-old Tibetan Buddhist monk has a brain that looks like he's just 33.

While there's no fountain of youth, a Tibetian Buddhist monk may have tapped into the next best thing, according to an analysis showing that his 41-year-old brain actually resembles that of a 33-year-old.

The monk, Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche (YMR), a renowned meditation practitioner and teacher, began meditating at age 9. The "extraordinary number of hours" that YMR spent meditating may explain why, in part, his brain looks eight years younger than his calendar age, researchers of a new longitudinal study said. (A longitudinal study looks at the same metric over time.)

The findings add to a growing pile of evidence "that meditative practice may be associated with slowed biological aging," the researchers wrote in the case study, published online Feb. 26 in the journal Neurocase.

Related: Mind games: 7 reasons you should meditate

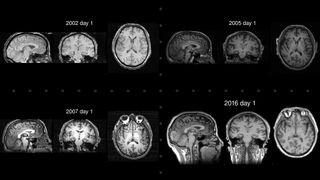

In the study, done at the Center for Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, researchers used structural MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) to scan the brain of YMR four times over the course of 14 years, starting when he was 27 years old.

During this time, 105 adults from the Madison, Wisconsin, area who were about the same age as YMR also had their brains scanned. These people became the control group, so researchers would know what normal brain aging looked like.

After the MRI scans were collected, the researchers used a machine learning tool called the Brain Age Gap Estimation (BrainAGE) framework, which estimates the age of a person's brain by looking at its gray matter.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Taking an inventory of gray matter structure is a good way to tell brain age, said the study's senior researcher, Richard Davidson, professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and founder and director of the Center for Healthy Minds. "Gray matter is the neural machinery of the brain," Davidson told Live Science. "When the brain atrophies, there is a decline in gray matter."

BrainAGE's analysis revealed that YMR's brain had delayed aging in comparison with the controls, who fell onto the "typical aging band" when graphed, the researchers found.

"The big finding is that the brain of this Tibetan monk, who has spent more than 60,000 hours of his life in formal meditation, ages more slowly than the brains of controls," Davidson said.

BrainAGE also showed that specific regions of YMR's brain didn't differ from controls, "suggesting that the brain-aging differences may arise from coordinated changes spread throughout the gray matter," the researchers wrote in the study.

Early maturity

In addition, the BrainAGE analysis found that YMR's brain had matured early. It's not clear what this means, Davidson said, although the researcher did offer one idea.

"There are areas of the brain that come online in the mid- to late 20s, for example, regulatory regions of the brain that play an important role in self-regulation, in regulating our attention," Davidson said. "It may be that these areas are maturing earlier in the meditators, and that would make sense, because we believe that meditation can strengthen these areas and these kinds of functions [in the brain]."

Other research by the Center for Healthy Minds shows that certain kinds of meditation can strengthen these regulatory skills, Davidson noted.

However, there is still much to learn. This case study examines just one meditator, and an accomplished one at that. It remains a mystery how much meditation is needed before these gray matter changes take place, Davidson said.

Furthermore, YMR's life is unique. At age 12, he was formally enthroned as the seventh incarnation of Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche. As a teenager, he became a retreat master, responsible for guiding senior monks and nuns through the intricacies of Buddhist meditation practice over a three-year period, the researchers wrote in the study. YMR continued to live an accomplished life, and he participates in studies, including this one, to help scientists learn more about meditation and the brain.

In short, it's unclear if his "young" brain is the result of meditation, other factors in his life or all of the above. For instance, it's possible that people born in the high mountains of Tibet have brains that age more slowly, Davidson said. Or maybe YMR has a healthy diet and lives in areas with less pollution. A control group of people with similar backgrounds to YMR might help researchers better suss out answers to these questions.

Davidson noted, however, that it's unknown whether having a young brain means that a person will live longer.

Even so, the study suggests that meditation can be healthy for those who practice it, said Dr. Kiran Rajneesh, a neurologist at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, who was not involved with the research.

"It kind of makes sense biologically, because stress is a thing that causes aging," Rajneesh told Live Science, "Not just psychological stress, which is definitely a part of it, but also stress happening at the cellular level."

Rajneesh added "it's definitely something each of us could take home. Perhaps doing those few minutes of meditation and slowing down our lives, even for some amount of time, is likely to help."

- 7 mind-bending facts about dreams

- 10 things you didn't know about the brain

- 11 facts every parent should know about their baby's brain

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular