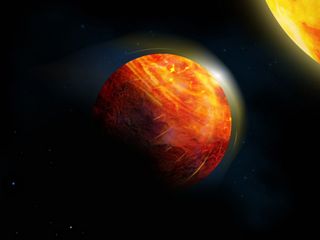

This bizarre planet could have supersonic winds in an atmosphere of vaporized rock

A lava ocean, atmosphere of vaporized rock, supersonic winds and rock glaciers, too?

Scientists think they have identified a lava world so dramatic that it might boast a thin regional atmosphere of vaporized rock where it is closest to its star.

That exoplanet is called K2-141b and was originally discovered in 2017. The world is about half again as big as Earth but orbits so close to its star, which is one class smaller than our own, that it completes several loops each Earth-day with the same surface permanently facing the star. Now, scientists predict those factors mean that two-thirds of the surface of K2-141b is permanently sunlit — so much so that not only is part of the world covered in a lava ocean, but some of that rock may even evaporate away into the atmosphere.

"All rocky planets, including Earth, started off as molten worlds but then rapidly cooled and solidified," Nicolas Cowan, a planetary scientist at McGill University in Canada and a coauthor on the new paper, said in a statement. "Lava planets give us a rare glimpse at this stage of planetary evolution."

Related: 7 ways to discover alien planets

The scientists behind the new researchers wanted to understand what sort of atmosphere such a hot world might have and how terrestrial tools would see it. K2-141b was a tempting target because it's been studied by both the K2 mission of NASA's Kepler Space Telescope and by the agency's Spitzer Space Telescope. And the atmosphere is particularly intriguing because scientists believe that NASA's upcoming James Webb Space Telescope, due to launch late next year, will be able to analyze the components of distant planetary atmospheres.

The researchers started with what previous studies have determined about K2-141b so far — for example, that the planet's density is about that of Earth's, so the crust can be modeled as pure silica as a reasonably simplified representation. Then, the scientists figured out what the surface might look like. That work took into account complications like the fact that the planet is so close to its star that more than half the world's surface might be sunlit, perhaps as much as two-thirds, the researchers calculated.

Such constant light and heat mean that the world likely sports a magma ocean tens of miles or kilometers deep, according to the team's calculations. Then, the researchers modeled what an atmosphere here would look like based on three potential main ingredients, all of which are common in the crusts of rocky planets.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All three cases can support an atmosphere, the scientists calculated, with wind speeds above 1.1 miles (1.75 kilometers) per second, far faster than the speed of sound here on Earth.

At the edges of the atmosphere, where temperatures drop, the gaseous rock would cool enough to fall back to the surface as precipitation, the researchers calculated. If the atmosphere is dominated by silica or silicon monoxide, that precipitation would mostly fall into the magma ocean, but if the atmosphere is predominantly sodium, the planet would look even weirder, with solid sodium oozing back toward the oceans like glaciers here on Earth, the researchers wrote.

But all this modeling wasn't just to envision what a truly bizarre world might look like; this is science, after all. The researchers wanted to compare their models with the current and predicted observing capacities of massive space telescopes. Here, the scientists are upbeat: they call K2-141b "an especially good target for atmospheric observations."

And the researchers even have a way to pass their time before the James Webb Space Telescope launches, the scientists said in the statement: they have acquired Spitzer Space Telescope observations that should help pin down the temperatures of the planet's day and night sides, clarifying how the models may match reality.

The research is described in a paper published Nov. 3 in the journal the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

Most Popular