Ancient Judeans ate non-kosher fish, archaeologists find

Jewish dietary laws that prohibit the eating of fish that don't have fins and scales didn't stop the ancient residents of Judea from frequently dining on non-kosher fish, a new study finds.

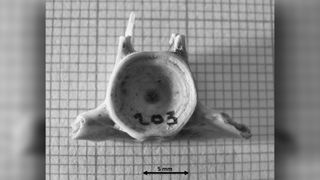

Clues to these ancient meals surfaced in thousands of tiny fish bones that were excavated from dozens of sites in what is now Israel and Sinai. New analysis of these bones shows that people in Judea (now southern Israel and part of Palestine's West Bank) regularly ate non-kosher fish such as catfish and sharks.

Many of these bones date to after the time when the prohibitions against such non-kosher, or "treif," foods were codified in the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, known as the Torah. For instance, fish bones appeared in locations all the way up to the Hellenistic period (332 to 63 B.C.).

But by the Roman period, around the first century A.D., few non-kosher fish bones show up in Judean archaeological sites. Over time, as knowledge of the prohibition became more widespread among "rank and file" Judeans, they likely started avoiding fish that were previously a staple of their diet, scientists reported in a new study.

Related: In photos: Rare Hebrew papyrus from Judean Desert

Warnings about eating certain types of fish appear in two of the Torah's five books: Leviticus and Deuteronomy, according to the study. In Leviticus 11: 9–12, the text declares that "of their flesh you shall not eat … everything in the waters that does not have fins and scales is detestable for you." The passage in Deuteronomy reiterates "whatever does not have fins and scales you shall not eat," labeling such fish "unclean." (Deuteronomy 14: 9–10)

Catfish have smooth skin that lacks scales, and sharks are covered by a layer of V-shaped structures called dermal denticles, which are more like teeth than scales, according to the ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research in British Columbia, Canada. That makes both treif according to kashrut (kosher) rules.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scholars date the writing and editing of the Torah to the Persian period, about 539 to 332 B.C., said lead study author Yonatan Adler, a senior lecturer in archaeology at Ariel University in the Israeli settlement of Ariel in the West Bank. But when did observance of these laws, such as the dietary prohibition against scale-less fish, become widespread among Judeans? To answer that question, Adler looked to the archaeological record, he told Live Science.

"When are regular people who aren't writing these books, who aren't among the intellectuals, the literati — when do they know about the Torah, and when are they observing it?" Adler said. "Archaeology is particularly well suited to uncovering what people are actually doing," he said. "The writings we find in the Bible, they tell us what a very small number of people were thinking. Archaeology is able to uncover what large numbers of people were actually doing."

Fishing for answers

Adler and study co-author Omri Lernau, an archaeozoologist with the Zinman Institute of Archaeology at the University of Haifa in Israel, reviewed data from 20,000 fish bones that Lernau had previously identified from 30 sites, dating from the late Bronze Age (1550 B.C. to 1130 B.C.), centuries prior to the writing of the Torah, to the Byzantine period (A.D. 324 to A.D. 640).

They found that consumption of non-kosher fish was common through the Iron Age; at one site, Ramat Raḥel, non-kosher fish made up 48% of the fish bones that were found there. In all locations and during all time periods, catfish were the most abundant non-kosher fish, followed by cartilaginous fish — sharks and rays — and, in two locations (Jerusalem and Tel Yoqne'am), freshwater eels.

"Let's imagine the Persian period is the time when the Pentateuch [the first five books of the Hebrew Bible] was written," Adler said. "Were people following its rules in the Persian period? As far as fish is concerned, the answer is, No, it doesn't look like it." It wasn't until the second century A.D. that archaeological evidence shows that most Jews were following the Torah's dietary prohibitions about non-kosher fish, Adler said.

This shows that the ancient Judeans changed their eating habits to reflect kashrut laws — at least, that's what they did where non-kosher fish were concerned, Adler and Lernau reported. With pork, another food famously forbidden by the Torah, the archaeological record tells a different story. Pigs were scarce in Judean sites, including older locations that predated the Torah's kashrut prohibitions. It's possible that Judeans rarely ate pork even before the Torah forbade it, because pigs were impractical to raise and feed, according to the study.

However, a "black hole" of evidence still lingers, hiding the transition into the time when Judaeans began omitting non-kosher fish from their diet. During the time when that shift happened — the Hellenistic period, as the first century B.C. was winding down — "we don't have enough data," Adler said. The researchers still don't know exactly when that transition began, he added.

"We're hoping future digs will uncover fish assemblages that will be able to answer that question," Adler said.

The findings were published online May 24 in the journal Tel Aviv.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular