Slime Mold Beats Humans at Perfecting Traffic Networks

Since the best city planners around the world have not been able to end traffic jams, scientists are looking to a new group of experts: slime mold.

That's right, a species of gelatinous amoeba could help urban planners design better road systems to reduce traffic congestion, a new study found.

A team of researchers studied the slime mold species Physarum polycephalum and found that as it grows it connects itself to scattered food crumbs in a design that’s nearly identical to Tokyo’s rail system.

Slime mold is a fungus-like, single-celled animal that can grow in a network of linked veins, spreading over a surface like a web. The mold expands by dividing its nuclei into more and more nuclei, though all are technically enclosed in one large cell.

"Some organisms grow in the form of an interconnected network as part of their normal foraging strategy to discover and exploit new resources," wrote the researchers in a paper published in the Jan. 22 issue of the journal Science. Slime mold has evolved to grow in the most efficient way possible to maximize its access to nutrients.

"[It] can find the shortest path through a maze or connect different arrays of food sources in an efficient manner with low total length, yet short average minimum distance between pairs of food sources," wrote the scientists, led by Atsushi Tero from Hokkaido University in Japan.

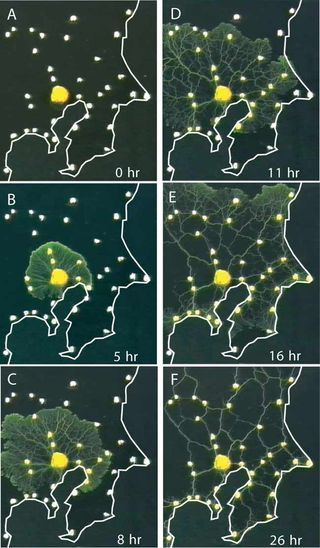

To test whether slime-mold networks behave anything like train and car traffic networks, the researchers placed oat flakes in various spots on a wet surface so that the resulting layout corresponded to the cities surrounding Tokyo. They even added areas of bright light (which slime mold tends to avoid) to correspond to mountains or other geologic features that the trains would have to steer around.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The scientists let the mold organize itself and spread out around these nutrients, and found that it built a pattern very similar to the real-world train system connecting those cities around Tokyo. And in some ways, the amoeba solution was more efficient. What's more, the slime mold built its network without a control center that could oversee and direct the whole enterprise; rather, it reinforced routes that were working, and eliminated redundant channels, constantly adapting and adjusting for maximum efficiency.

To take advantage of what nature and evolution have spent millennia perfecting, the researchers fed information about the slime mold's feeding and growing habits into a computer model, and hope to use it to design more efficient and adaptive transportation networks.

"The model captures the basic dynamics of network adaptability through interaction of local rules, and produces networks with properties comparable to or better than those of real-world infrastructure networks," Wolfgang Marwan of Otto von Guericke University in Germany, who was not involved in the project, wrote in an accompanying essay in the same issue of Science.

"The work of Tero and colleagues provides a fascinating and convincing example that biologically inspired pure mathematical models can lead to completely new, highly efficient algorithms able to provide technical systems with essential features of living systems."

- 10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Live

- The Science of Traffic Jams

- Video: Flying Cars