Dinosaur-Era Shark Nabbed Flying Reptile, Losing a Tooth

More than 80 million years ago, a winged reptile called a pteranodon bobbed placidly on the waves of the Western Interior Seaway, which ran straight through what is today North America. Suddenly, the water below the flying reptile erupted into froth, teeth and sharkskin. When the chaos cleared, the pteranodon was dead and a monster of a shark was missing a tooth.

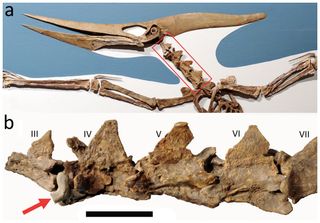

That's the picture painted by a new paper published online Dec. 14 in the journal PeerJ about a curious fossil: a partial skeleton of a Late Cretaceous pteranodon with a nearly 1-inch-long (24 millimeters) shark tooth embedded in its neck.

Granted, the researchers wrote, the story could be a bit more mundane. Perhaps the shark simply scavenged the floating carcass of an already-dead pteranodon. Either way, the fossil is a rare record of the sea and the sky meeting in the time of the dinosaurs.

"We've got good direct evidence that a good-sized shark took a chunk out of a big flying reptile over 80 million years ago," said study co-author Michael Habib, a paleontologist at the University of Southern California's Keck School of Medicine. "It's pretty cool." [Photos of Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs]

A toothy mystery

The fossil with the tooth embedded is on public display at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, but it was found in Kansas in 1965. In the Late Cretaceous, what is today Kansas was under the shallow Western Interior Seaway, which covered much of the center of North America. The species of pteranodon in this find is unknown, but it likely lived between about 86 million and 83 million years ago. It was a big animal, with a wingspan about 16.4 feet (5 meters) across.

The shark tooth belonged to a species called Cretoxyrhina mantelli, which is now extinct. Sharks of this species could have grown as long as 23 feet (7 m), but based on the tooth size, Habib and his colleagues estimated that the one that bit the pteranodon was about 8 feet (2.5 m) long.

Habib and his colleagues decided to study the specimen after it was pulled out of storage and put on permanent display in the museum. Tour guides pointed out the tooth to visitors, Habib said, and visitors asked how paleontologists knew the tooth came from a bite, rather than just drifting into the pteranodon's carcass during fossilization. It was a good question, Habib said, so the research team decided to tackle it. (Habib is a research associate at the museum.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Shark vs. pteranodon

The first thing the team found is that the fossil very likely does capture a shark-versus-pteranodon moment. The tooth is wedged well under one of the protrusions of a vertebrae, Habib said, which would require a lot of strong current if it simply drifted there. The sediment where the fossils were found, though, indicates relatively placid waters.

"There's no way for it to drift into that position," Habib said.

Though there will never be a way to know for sure whether the shark hunted or scavenged the pteranodon, the authors presented a reconstruction of the possible scene, showing a shark breaching the water to snatch its prey. Modern sharks sometimes do this, Habib said. They get up a full head of steam to hit a floating seabird as fast and as hard as possible, breaking the water's surface as they grab the bird.

The ancient shark likely would have also hunted in this way, Habib said, because biomechanics studies on pteranodons suggest that the creatures would have been able to take off from the water in about a second and a half. That's slow enough for a shark to catch such prey, but the toothy fish would have to be quick.

"What we can say is the body morphology and size and shape of these sharks should allow them to do that," he said. "It's probably a pretty good way of catching a flying reptile like this."

- Photos: Ancient Pterosaur Eggs & Fossils Uncovered in China

- Photos: Baby Pterosaurs Couldn't Fly As Hatchlings

- Megalodon Mystery: What Killed Earth's Largest Shark?

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular