38 Baby Skulls of Weird Jurassic-Era Mammal Relative Found

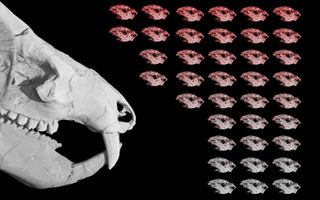

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — About 185 million years ago, a hairy, beagle-size animal celebrated motherhood by having 38 babies in the same clutch, according to a new study of the skeletal remains of both mama and babes.

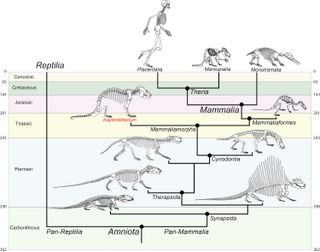

The animal, known as Kayentatherium wellesi, wasn't quite a mammal, but rather a cynodont, a mammal relative that lived during the Jurassic period. And the prodigious number of babies she had is more than twice the average litter size of any mammal living today, meaning that K. wellesi reproduced more like a reptile, the researchers said.

Moreover, these babies had remarkably small brains, suggesting that as mammals developed, they traded off small brains and big litter sizes for larger brains and smaller litter sizes, the researchers said. [In Photos: Mammals Through Time]

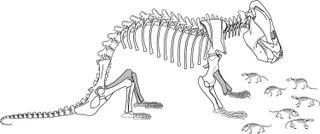

The discovery of the mother and her 38 offspring is extraordinarily rare, because these are the only known babies of a mammal precursor on record, the researchers said. Even though no eggshells were found at the site, the young were likely still developing inside eggs or had just hatched when they met their untimely deaths, according to the study, which was published online Aug. 29 in the journal Nature and presented here Oct. 18 at the 78th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting.

"These babies are from a really important point in the evolutionary tree," study lead researcher Eva Hoffman, a graduate student of geosciences at the University of Texas, said in a statement. "They had a lot of features similar to modern mammals, features that are relevant in understanding mammalian evolution."

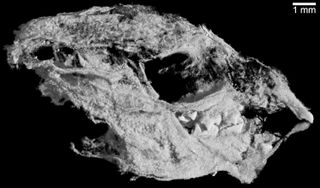

The fossils were discovered more than 18 years ago in the early Jurassic Kayenta Formation of northeastern Arizona by study co-researcher Timothy Rowe, a professor of geoscience at the University of Texas. At first, Rowe thought the rock chunk he had excavated contained a single specimen. It wasn't until Sebastian Egberts, a former graduate student and fossil preparator at the University of Texas, began unpacking the slab in 2009 that he noticed a speck of tooth enamel in the rocky slab.

"It didn't look like a pointy fish tooth or a small tooth from a primitive reptile," Egberts, who is now an instructor of anatomy at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, said in the statement. "It looked more like a molariform [molar-like] tooth — and that got me very excited."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Micro-computed tomography (CT) scans revealed that the rock chunk included not just the mother, but also the jaws, teeth, skulls and partial skeletons of the babies. An anatomical analysis showed that the tiny bones were the same species as the adult. In addition, the babies' skulls had the same proportions as the adult, even though they were merely a tenth of the size.

In contrast, mammal babies are born with shortened faces and bulbous heads, which hold their big brains, the researchers said.

It's energy-intensive to have a big brain, and sizable noggins also make childbearing extremely challenging. Given that K. wellesi had a tiny brain and dozens of babies, it appears that the step in which mammals traded litter power for brain power hadn't happened yet in the early Jurassic, the researchers said.

"Just a few million years later, in mammals, they unquestionably had big brains, and they unquestionably had a small litter size," Rowe said in the statement. [Photos: These Mammal Ancestors Glided from Jurassic Trees]

The discovery of K. wellesi and her babies "is a once-in-a-lifetime type discovery that can have a huge impact on how we view mammal biology," Greg Wilson, an associate professor of biology and curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Washington, told Live Science.

"Our reproductive biology is such a central component to being mammal," Wilson said. "This fossil gives us a snapshot of the reproductive biology of an animal that was not quite mammalian yet. It gives us a window into the transition from what it means to be reptile to what it means to be mammalian."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.