Hidden Maya Civilization Revealed Beneath Guatemala's Jungle Canopy

More than 61,000 ancient Maya structures — from large pyramids to single houses — were lurking beneath the dense jungle canopy in Guatemala, revealing clues about the ancient culture's farming practices, infrastructure, politics and economy, a new aerial survey has revealed.

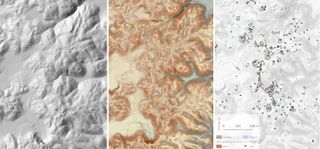

The Guatemalan jungle is thick and challenging to explore, so researchers mapped the terrain with the help of a technology known as light detection and ranging, or lidar. The lidar images were captured during aerial surveys of the Maya lowland, a region spanning more than 810 square miles (2,100 square kilometers). [See Photos from the Maya Lidar survey]

"Since lidar technology is able to pierce through thick forest canopy and map features on the Earth's surface, it can be used to produce ground maps that enable us to identify human-made features on the ground, such as walls, roads or buildings," Marcello Canuto, director of the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University in New Orleans, said in a statement.

The aerial lidar survey covered 12 separate areas in Petén, Guatemala, and included both rural and urban Maya settlements. After analyzing the images — which included isolated houses, large palaces, ceremonial centers and pyramids — the researchers determined that up to 11 million people lived in the Maya lowlands during the late Classic period, from A.D. 650 to 800. This number is consistent with previous calculations, the researchers noted in the study, which was published online Friday (Sept. 28) in the journal Science.

It would have required a massive agricultural effort to sustain such a big population, the researchers said. So, it was no surprise when the lidar survey revealed that much of the wetlands in the area were heavily modified for farming, the researchers said.

In all, the surveys revealed about 140 square miles (362 square km) of terraces and other modified agricultural land, as well as another 368 square miles (952 square km) of farmland.

In addition, the lidar analysis uncovered 40 square miles (110 square km) of roadway networks within and between faraway cities and towns, some of which were heavily fortified. This finding highlighted the links between the Maya's hinterlands and urban centers, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Seen as a whole, terraces and irrigation channels, reservoirs, fortifications, and causeways reveal an astonishing amount of land modification done by the Maya over their entire landscape on a scale previously unimaginable," Francisco Estrada-Belli, a research assistant professor of anthropology at Tulane University and director of the Holmul Archaeological Project, said in the statement.

However, even though the lidar evaluation revealed so many previously unknown structures, researchers described it as a complement to, but not a replacement for, traditional archaeology. In a perspective article on the new research published in the same journal, Anabel Ford, an adjunct professor of archaeology at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Sherman Horn, a visiting professor of archaeology at Grand Valley State University in Michigan, wrote that even with lidar, "boots on the ground" would always be needed.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular