A Woman Had Strange Feelings in Her Legs. Doctors Found Parasites in Her Spine

This article was updated on July 12.

When the 35-year-old woman arrived at a hospital in France, she told doctors it felt like electric shocks were running down her legs. What's more, she felt weak and had experienced a number of falls recently.

The woman's unusual symptoms turned out to have a surprising cause: Tapeworm larvae lurking in her spine, according to a new report of the case, published today (July 11) in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The woman lived in France and told doctors that she hadn't been out of the country recently. But she said she did ride horses and have contact with cattle. In addition to her other symptoms, the woman said that over the last three months, she'd had difficulty riding her horse, according to the report.

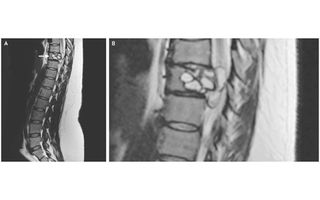

An MRI revealed a lesion on her spine, at her ninth thoracic vertebra, which is located in the middle of the back, the report said. [8 Awful Parasite Infections That Will Make Your Skin Crawl]

The woman needed surgery to remove the lesion, and tests revealed that it was caused by an infection with Echinococcus granulosus, a small tapeworm that's found in dogs and some farm animals, including sheep, cattle, goats and pigs.

This tapeworm can cause a disease called cystic echinococcosis, also known as hydatidosis, in which the larvae form cysts that grow slowly in a person's body, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These cysts typically grow in the liver or the lungs, but they can also appear in other parts of the body, including the bones and the central nervous system. However, infections of the bones, including the spinal column, are rare, making up just 0.5 to 4 percent of cases of this disease, according to a 2013 paper on cystic echinococcosis.

The life cycle of Echinococcus granulosus is somewhat complex: The "adult" form of the worm lives in the intestines of dogs and can grow to be 6 millimeters (0.2 inches) long, according to the CDC. Tapeworm eggs are passed in the dogs' stool, and other farm animals become infected when they ingest food or water that's contaminated with the tapeworm eggs. Once ingested by farm animals, the eggs develop into larvae, but they cannot develop into adult worms until they are again ingested by dogs (which can happen if dogs are fed slaughtered livestock, according to the CDC.)

Humans become infected with Echinococcus granulosus when they ingest the tapeworm eggs, which can happen if people consume food or water that's contaminated with stool from infected dogs, according to the CDC. For example, a person might become infected if they consumed plants or berries gathered from fields where infected dogs have been. Humans are considered "accidental" hosts, because they aren't involved in transmitting the disease back to dogs, according to the World Health Organization. (The worms can't grow into adults in humans.)

Dr. Lionel Piroth, an infectious-disease specialist at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Dijon, who treated the woman, said that cystic echinococcosis "is very rare in France," and it wasn't clear how the woman got the infection. She did not report having any contact with dogs, he said.

One possibility is that the woman could've gotten sick by eating vegetables that were contaminated with the parasite, Piroth told Live Science. (If this were the case, the vegetables would've been contaminated by an "unknown" dog, he noted.) Adding to the mystery, the woman was the only one in her family to be infected.

In addition to surgery, the woman was treated with an anti-parasitic medication. Nine months later, she had no lingering symptoms of her infection or signs that it was coming back, the report said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated on July 12 to add comments from Dr. Piroth.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.