Buried Volcanic Vent Heats Up Antarctica's Fastest-Melting Glacier

What lurks beneath western Antarctica's frozen surface? Volcanic heat, according to a new study. And that extra warmth might be speeding up the disappearance of the Pine Island Glacier, the continent's fastest-melting glacier.

Chilly Antarctica hides much under thick layers of ice, which extend for miles over its bedrock. Scientists previously found a volcanic rift system stretching under West Antarctica and into the Ross Sea, with as many as 138 volcanoes identified. However, those volcanoes have been dormant for 2,200 years, and evidence that turned up near the Pine Island Glacier pointed to recent magma activity deep underground, the researchers reported.

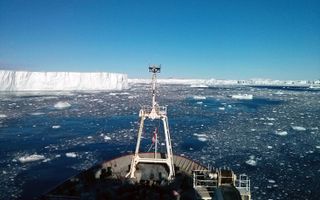

Volcanoes typically announce themselves by belching smoke and gas into the air, but in Antarctica, the heat source was buried under miles of ice. However, even though the magma itself was hidden, scientists could spot its "fingerprints" in certain gases they found in seawater samples. The chemistry of melted ice running off the glacier hinted at a volcanic source upstream, warming the ice from below and accelerating melt into the Amundsen Sea. [Photo Gallery: Antarctica's Pine Island Glacier Cracks]

Viewed on a map, Antarctica somewhat resembles a tilted, thumbs-up emoji. To the west is the "thumb" — the Antarctic Peninsula — protruding outward from West Antarctica, with the Pine Island Glacier, which has an ice shelf, or tongue of ice, that extends from it, at the thumb's base. The "hand" of the emoji is East Antarctica, and the eastern and western regions are bisected by the Transantarctic Mountains.

In terms of recent ice loss, West Antarctica has fared far worse than its eastern counterpart, and Pine Island Glacier has been especially hard-hit. Since 2012, about 175 billion tons (159 billion metric tons) of ice have disappeared from West Antarctica each year. In February 2017, Pine Island Glacier lost a chunk of ice measuring about 1 mile wide (1.6 kilometers), and in September of that year, another massive chunk separated from the glacier, measuring roughly four times the size of Manhattan.

It's a gas, gas, gas

The scientists who found the evidence of volcanism weren't even looking for volcanoes. A 2014 expedition brought them to the Pine Island Glacier to sample seawater so they could detect melting patterns and the history of melting ice, both of which are recorded in certain types of gases in the water, lead study author Brice Loose, a chemical oceanographer and an assistant professor at the University of Rhode Island's Graduate School of Oceanography, said in a statement.

"I was sampling the water for five different noble gases, including helium and xenon," Loose said. "I use these noble gases to trace ice melt as well as heat transport."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But one of the gases that showed up in their samples in high concentrations near Pine Island Glacier surprised the scientists: helium-3, a nonradioactive helium isotope. Helium-3 is a signature of volcanism, as it is found almost exclusively in Earth's mantle, the layer just beneath the planet's crust.

Gauging by the amount of helium-3 in the water, the heat under the glacier is "substantial," and Pine Island Glacier is currently losing mass faster than any other glacier in Antarctica, the study authors reported. However, it is not yet clear how much this newly discovered heat source contributes to the glacial melt, which is spurred primarily by warming ocean currents, Loose said in the statement. Collapse of the Pine Island Glacier could have grave consequences for global sea-level rise, and identifying a new source of volcanic warmth will help researchers form better predictions of the ice sheet's future stability, the scientists concluded.

The findings were published online June 22 in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.