No Needles: Contact Lens Could Monitor Glucose for People with Diabetes

Many people with diabetes need to prick their finger for a drop of blood up to eight times a day to monitor their glucose levels, an uncomfortable and cumbersome task. It can all add up to tens of thousands of finger pricks over a person's lifetime.

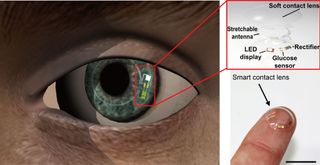

Now, South Korean researchers may have a means of measuring blood sugar without a finger prick in sight: The scientists developed a glucose monitor embedded in a soft contact lens that measures glucose levels in tears and transmits that information wirelessly to a handheld device… and you don't even need to cry.

The device has been tested so far only on live rabbits, with no signs of discomfort. But the researchers who created the device predict that this sugar-sensing contact lens may be available commercially for people in less than five years. The device would be placed in one eye and not be used to correct vision, like traditional contact lenses. ['Eye' Can't Look: 9 Eyeball Injuries That Will Make You Squirm]

The device is described today (Jan. 24) in an article published in the journal Science Advances.

More than 30 million Americans, or 9.4 percent of the U.S. population, have type 2 diabetes, and another 80 million have prediabetes, a condition that if not treated often leads to type 2 diabetes within five years, according to a 2017 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes is a health concern in South Korea, as well, where the rate rose from 5.6 percent in 2006 to 8 percent in 2013, according to data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service.

Diabetes is a condition in which the body periodically has levels of blood sugar, or blood glucose, that are higher than normal. The cause might be the pancreas's inability to produce enough insulin to help metabolize the glucose (called type 1 diabetes) or, much more common, the body's inability to use insulin properly (called type 2 diabetes).

In either case, many (but not all) of those with diabetes need to monitor their glucose levels through the course of the day. Prolonged, elevated glucose levels can damage blood vessels and increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, vision problems and nerve problems.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A glucose-sensing lens

Previous attempts to embed glucose monitors into a contact lens had been fraught with difficulties. The electronics were too brittle and the lenses were too rigid, leading to a fragile device that was both uncomfortable and prone to breaking, said lead study author Jang-Ung Park, a professor of engineering at Ulsan National Institute of Science & Technology in South Korea. Elements in these earlier devices blocked vision, too, and would potentially damage the eye, according to the paper.

But advances in materials science and nanotechnology in recent years have enabled Park's team to design flexible, or stretchable, structures and circuits, including an LED display embedded in the lens.

The resulting product measures glucose levels in real time in natural tear secretions and relays this data through LED display that can emit a non-intrusive light if glucose levels get too high. Or, with the inclusion of a miniature antenna in the lens, information can be transmitted wirelessly.

"The key difference is the soft lens with stretchable electronics and displays," Park told Live Science. "This soft contact lens is stretchable and can be turned over. So, the LED light can be emitted into the [eye of the] wearer or into the opposite direction, dependent on the wearer's choice."

Glucose monitoring is optional for some people who don't need insulin injections. But everyone who uses insulin to regulate their condition must do finger sticks for blood glucose testing, even if only to calibrate the glucose monitor. This includes the 1.25 million Americans with type 1 diabetes and another approximately 6 million with type 2 diabetes, according the American Diabetes Association (ADA).

A blood sample from a finger stick is the gold standard for accurate blood glucose measurements. Techniques have been available for years to measure glucose in tears, but measurements tend not to be as accurate for a variety of factors; for example, glucose concentrations can be lower when your eyes are more watery from allergies or crying.

"Tear glucose levels do vary in relation to blood glucose levels, [so] much research still needs to be done to clarify the correlation and how closely tear glucose levels track with blood glucose levels," Matt Petersen, managing director of medical information for the ADA, told Live Science.

However, the researchers who have created the new lens-based device said that monitoring glucose via tears may serve as a convenient proxy to blood measurements because it is done continually in real time, compensating for sampling inconsistencies.

Petersen noted that, while there are challenges in testing tears, the potential to eliminate finger sticks is something that would likely appeal to people with diabetes.

The researchers hope that their technique of embedding sensors on soft contact lenses also can be applied to other areas, such as smart devices for drug delivery, augmented reality and even biomarker monitoring via a smartphone.

Follow Christopher Wanjek @wanjek for daily tweets on health and science with a humorous edge. Wanjek is the author of "Food at Work" and "Bad Medicine." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on Live Science.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.