508-Million-Year-Old Bristly Worm Helps Solve an Evolutionary Puzzle

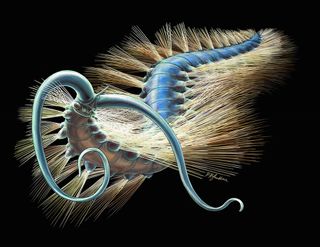

An eyeless, alien-like worm with two tentacles sprouting out of its head and covered in so many bristles it looked like a kitchen brush would have been quite a sight during its heyday as it scarfed down seafloor mud some 508 million years ago.

Scientists discovered the exquisitely preserved remains of the bizarre, soft-bodied creature in British Columbia, Canada. Like other bristle worms, the newfound critter has hair-size bristles poking out of its body. "However, unlike any living forms, these bristles were also partially covering the head, more specifically surrounding the mouth," the study's lead author Karma Nanglu, a doctoral student in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto and a researcher at the Royal Ontario Museum, said in a statement.

By analyzing the fossils (and intriguing noggin), researchers were able to solve an evolutionary mystery about how ringed worms, a group that includes modern earthworms and leeches, developed their heads. The newly identified critter "seems to suggest that the annelid head evolved from posterior body segments that had pair bundles of bristles, a hypothesis supported by the developmental biology of many modern annelid species," Nanglu said. [See images of the bristly, eyeless worm]

Bristly find

Researchers uncovered more than 500 individual worm fossils from 2012 to 2016 in Marble Canyon, a site within the well-known Burgess Shale deposit.

"The fossils of the Burgess Shale are some of the most important in the world, documenting a phenomenon known as the Cambrian Explosion: the first appearance of most modern animal groups in the fossil record," Nanglu told Live Science.

The bristly worm was tiny, just 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long. But this teeny body sported a ton of bristles — each of its up to 25 body segments sported 56 bristles apiece, and it also had two long tentacles on its head. Smaller antennae between its tentacles likely helped the worm scan the area directly in front of it, while the tentacles could extend farther, Nanglu said.

The scientists named the critter Kootenayscolex barbarensis. The genus name references Kootenay National Park in British Columbia, where Marble Canyon is located, and includes " scolex," the Greek word for "worm." The species name honors Barbara Polk Milstein, a volunteer at the Royal Ontario Museum who helps with Burgess Shale research, Nanglu and his colleague, study co-author Jean-Bernard Caron, wrote in the study. Caron is the senior curator of invertebrate palaeontology at the Royal Ontario Museum.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

K. barbarensis was likely a deposit feeder that engorged itself with mud on the seafloor, Nanglu said. "These organisms funnel mud into their mouths that they then sift through for organic material to feed on," he said. "We get evidence for this way of life from the well-preserved gut of Kootenayscolex, which often preserves much more darkly [in color] compared to the surrounding tissue."

In addition to looking at K. barbarensis under the microscope, the researchers used a technique called elemental mapping. This method visualizes the elemental composition, such as carbon or calcium, on the fossil's surface.

"The layout and composition of these elements helps us hypothesize about what types of tissues the animal originally possessed," Nanglu said. "In this case, we think that a number of the pronounced, dark areas in the fossil represent degraded vascular tissue."

The findings were published online today (Jan. 22) in the journal Current Biology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Most Popular