Roman Temple of Mithras May Align with Sun on 'Jesus' Birthday'

An 1,800-year-old temple in northern England that is dedicated to the god Mithras was built to align with the rising sun on Dec. 25, a physics professor has found.

The temple is located beside a Roman fort in Carrawburgh, near Hadrian's Wall, which served as the most northerly frontier to the Roman Empire, beginning around A.D. 122.

Some modern-day scholars believe that the Romans celebrated Mithras' birthday on Dec. 25 — the same day eventually chosen by Christians to celebrate the birth of Christ. (Scholars don't really think Jesus was born on that day.)

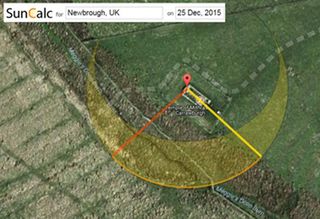

Using satellite imagery and astronomical software that shows the direction of the sunrises and sunsets, "we can easily see that the building is in good alignment along the sunrise on December 25," wrote Amelia Carolina Sparavigna, a physics professor at the Politecnico di Torino in Italy, in a paper published online recently in the journal Philica. The paper has not been peer reviewed. [In Photos: Peru Pyramid Shows Solstice Alignment]

"It means that, probably, the orientation of the temple was chosen to recall the birth of Mithras on December 25," Sparavigna added in the paper.

Scholars know that Mithras was popular among soldiers who served in the Roman army, because temples dedicated to the god are sometimes found near Roman forts.

"Mithras is the god of light, the new light which bursts forth each morning from the vault of heaven behind the mountains and whose birthday is celebrated on 25 December," wrote Manfred Clauss, a history professor at Goethe University Frankfurt, in his book "The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries" (Routledge, 2001).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Winter solstice

There is also an alignment between the Mithras temple and the rising sun on the winter solstice, the shortest day of the year, Sparavigna said. The winter solstice occurs on Dec. 21 during 2017.

Roger Beck, an emeritus professor of Classics at the University of Toronto, who has written extensively on the cult of Mithras, said that he hypothesized that such an alignment existed in a paper published in 1984 in the journal Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen. In that 1984 paper, he speculated that the rays of the sun might have illuminated a statue and altar within the Mithras temple on the winter solstice. After reviewing Sparavigna's research article, Beck commented that "the main point about alignment to the winter solstice I think stands, though not to the level of detail that I then proposed," regarding the statue and altar.

In his 1984 paper, Beck did not propose that the reason for such an alignment was to celebrate the birthday of the god Mithras on Dec. 25, and he's skeptical that the Romans celebrated the god's birth on that day.

While ancient texts indicate that the birthday of Sol Invictus — a sun god who became popular in the Roman Empire during the reign of Emperor Aurelian (reign A.D. 270 to 275) — was celebrated on Dec. 25, there is little evidence that the Romans believed that Mithras was also born on that day, Beck argued in a paper published in 1987 in the journal Phoenix.

More alignments?

Other temples dedicated to Mithras exist throughout the Roman Empire, and more research is needed to determine whether any of them align with the rising sun on the winter solstice or on Dec. 25, Sparavigna said.

In a separate paperpublished recently in the journal Philica, Sparavigna proposed that another Mithras temple near a Roman fort in Rudchester, in northern England, may be aligned like the temple at Carrawburgh.

Vance Tiede, an archaeologist with the company Astro-Archaeology Surveys, is in the process of researching astronomical alignments of Mithras temples, and he presented some preliminary results in September at the Joint 17th Conference of the Italian Society for Archaeoastronomy.

Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.