Armored 'Pinecone' Fish's Insides Revealed in Spooky Scan

From the outside, the pinecone fish is a colorful yet fearsome beast. On the inside, it's downright spooky.

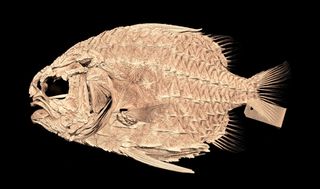

A new scan of a fish of the genus Cleidopus, posted on Twitter, looks like the re-creation of a monster from a sci-fi horror flick. In actuality, the scan reveals the tough, spiked armor of this denizen of the tropical and subtropical Indo-Pacific.

Pinecone fish grow about 8 inches (20 centimeters) long and come by their nickname honestly: Their scales are yellow, crisscrossed with black markings in the shape of the scales of a pinecone. (The fish are also known as "pineapple fish," another name that references their striking markings.) Running down the fish's sides are rows of small, nasty-looking spikes. Pinecone fish live at relatively deep ocean depths, down to 650 feet (200 meters) or so, and their jaws are studded with two bioluminescent organs, called photophores. These give off a greenish glow that the fish might use to attract prey. [See Photos of the Freakiest-Looking Fish]

"They're just really weird fish for a lot of reasons," said Matthew Kolmann, a postdoctoral researcher at of the University of Washington's Friday Harbor Laboratories, who made and posted the scan. Kolmann and his team, however, were interested in the fish's bony armor.

Armored skeleton

The computed tomography (CT) scan of the fish reveals that the spiky pinecone pattern is more than skin-deep. The fish is protected by a formidable layer of bony armor, built from small sections called scutes.

"It's incredibly intricate, seemingly ornate, thick, overlapping plates," Kolmann told Live Science in an email. "We knew from seeing them in collections and in aquariums that they had armor plating, but there's something about seeing the skeleton by itself where we realized, 'Oh, man, it seems like the majority of their skeleton is armor.'"

It was an exciting view for Kolmann and his colleagues, who are interested in the way that bony armor evolved among fish. Fish are a particularly useful group through which to study biodiversity, Kolmann said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"I work with fishes because there's over 30,000 species (over half the vertebrates), and if you're interested in some weird behavior or anatomy, odds are fish have done it, are doing it or will do it," he said.

Scan them all

The scanned pinecone fish was a loan from the California Academy of Sciences, where ichthyologist Graham Short is working to understand to the armor of seahorses and their relatives. Little was known about fish armor in general, Short and Kolmann soon discovered, prompting the pinecone fish collaboration.

Kolmann posted the resulting images under the hashtag #scanallfishes, the brainchild of Friday Harbor Labs' researcher Adam Summers.

"He's been using CT scanning to investigate fish anatomy for years and years, and he'd send pictures of the scans to collaborators or post them to social media," Kolmann said. "People would ask, 'What are you going to scan next?' and he'd just say that eventually we'd scan them all."

The hashtag has become a repository of sorts of fish CT scans from many research labs. So far, Kolmann said, the researchers at Friday Harbor Labs have scanned about 2,500 species.

"I'd say a couple times a week, we rush into the scanning room to see something truly weird and novel," he said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.