The Lore and Lure of Unicorns

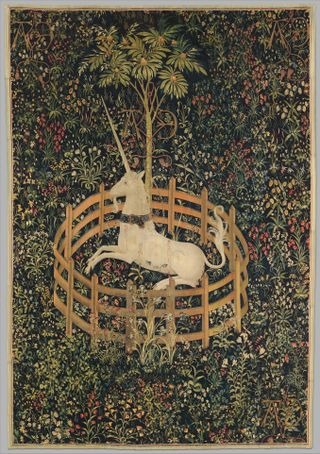

Along with mermaids and dragons, unicorns are among the world's best-known mythical creatures. From early artistic representations by Albrecht Durer and medieval tapestries to kitschy New Age posters and kids' T-shirts, unicorns are universally beloved. We all recognize the striking image, but the story behind the magnificent beast is equally enchanting.

The unicorn did not spring fully formed in the popular imagination; instead, it gradually evolved from numerous early sources. First reports of the unicorn date back to the fourth century when Greek physician Ctesias recorded exotic tales he'd heard from travelers: "There are in India certain wild asses which are as large as horses, and larger. Their bodies are white, their heads dark red, and their eyes dark blue. They have a horn on the forehead which is about a foot and a half in length." The horn, he added, was said to be white, red, and black.

The legends spread, and different cultures spawned various versions of the unicorn. The ki-lin of Chinese lore — which had a 12-foot-long horn on its head and a coat of five sacred colors — was renowned for bringing good luck. Though modern images tend to assume unicorns are horse-sized, the Physiologus (a 12th-century bestiary) described it as "a very small animal, like a kid." The comparison is to a baby goat instead of a preteen human, but in either event the unicorns described wouldn't stand much above knee height.

Unicorns, like mermaids, were long thought to be real. Both were based on legends and first-hand accounts from travelers to distant regions. Unicorns have a rich pedigree, having been discussed by luminaries such as Aristotle, Julius Caesar and Marco Polo. Belief in unicorns increased with the invention of printing and distribution of the Bible, which mentions the creatures at least seven times in the Old Testament.

There was no shortage of information about unicorns, provided by rumors and legends, but the regal beast itself remained elusive. For centuries, many believed that unicorns were surely real enough — after all, a great number of stories and artworks were devoted to the fine beasts — and perhaps lived in faraway lands. Others believed that the unicorn was once alive but went the way of the dodo, hunted to extinction.

Symbol of purity

Unicorns are freighted with symbolism and often depicted as white, representing purity. Though virtuous, unicorns are said to be quite enamored of themselves and fall prey to vanity, spending hours admiring themselves in silvered mirrors. (Despite YouTube videos and Internet memes to the contrary, there is no evidence that unicorns poop glitter or fart rainbows.)

Unicorns are said to be powerful and feral, thwarting all brutish efforts to capture them. Only through guile can the unicorn be tamed or taken: it requires setting a trap for the beast, and the cooperation of a virgin.

The procedure is this: First, find a forest where unicorns are known or suspected to live; then locate a clearing and find a place for a virgin to sit (a tree stump or fallen log should do), and have her wait quietly. Unicorns are said to be drawn by the presence of a virtuous maiden, and let their guard down only in her presence — whereupon hunters lying in wait could then capture or kill the fine beast.

Unicorn horns

Why would anyone want to capture or kill a unicorn? For its horn, of course.

The unicorn's horn was greatly valued for centuries. It had a variety of magical powers (most of them related thematically to its purity), including purifying rivers and lakes and neutralizing poison. The latter quality was much prized by kings who were paranoid about being poisoned — a real concern for monarchs fearful of being dispatched by rivals and heirs alike.

In her book "The Unicorn" (1980, Penguin Books), Nancy Hathaway tells the story of how England's King James I determined whether or not the unicorn horn he'd purchased for a kingly sum was authentic: "James summoned a favorite servant and instructed him to drink a draught of poison to which powdered unicorn horn had been added. The servant did so, and James could not have been more unpleasantly surprised when the servant promptly expired." (The king presumably kept the receipt and requested a refund.)

In the 1600s, London newspapers contained advertisements for miracle elixirs made of "true Unicorn Horn," which was said to relieve a laundry list of diseases and symptoms including ulcers, scurvy, melancholy, consumption, fainting spells, and "King's evil" (swelling of the lymph nodes, often due to tuberculosis). The unicorn preparation was available in both liquid form (patients should drink four ounces at a time, "the oftener the better") and as pills (twelve to a box), both available for a mere two shillings.

Some authors have whimsically suggested that the unicorn was hunted to extinction for its horn, in a tragic parallel to the fate of several rhino species in Africa. The horns are sold as trophies or ground up and used in traditional Chinese medicine as miracle cures.

The lion is said to be the unicorn's enemy, perhaps due to its stature as King of the Jungle, and many illustrations attest to competitions between the two. Poet Edmund Spenser's "The Faerie Queene" from 1590 describes a bitter rivalry between the animals, though they appear together on the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom, the lion representing England and the unicorn representing Scotland.

Belief in unicorns had waned by the Age of Enlightenment (around the 1700s) as more and more of the world was explored and the animals were not found. Shakespeare's reference to unicorns in "The Tempest" ("Now I will believe that there are unicorns") is a sarcastic one, and reflected an acknowledgement among many of the age — however reluctantly — that unicorns existed only in stories and fairy tales.

The historical unicorn is but lore and legend, though one-horned animals do seemingly exist. The rhinoceros does not have a true horn, however; it is instead hair tissue that grows together to form a horn shape. Then there's a marine version, the narwhal, a medium-sized whale whose tusk resembles a horn and was once known as a "sea unicorn."

Nonetheless, modern "unicorns" can be made. In the 1980s a "unicorn" (actually a goat with surgically implanted horn buds that grew together) was displayed at fairs and circuses, much to the chagrin of animal rights groups. A U.S. Department of Agriculture investigation determined that the animal was healthy and thus the show was allowed to go on, but the "unicorn" was retired in 1987.

Two millennia after the unicorn was first described, the regal beast remains as popular an image as ever: strong, virtuous, and always capable of inspiring mystery and fantasy.

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.