Eye Spy: Stem Cells Discovered in Eyeball

Hiding in the back of your eye are stem cells from the central nervous system, scientists have discovered. These stem cells can turn into fat, brain and other types of cells, and could be used to regenerate damaged tissues in the body.

In the future, the researchers said, they hope to figure out how to switch on these stem cells within the eye, allowing diseased eyes to heal themselves, though that's a long way off.

The finding has the potential to help treat eye diseases like macular degeneration, and could also explain weird diseases where non-eye tissue grows in the eyes.

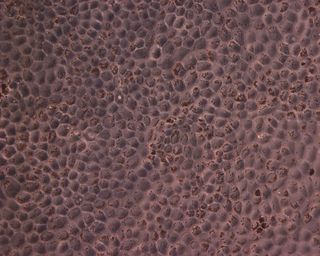

The stem cells in question were found in a special layer of cells in the eye called the retinal pigment epithelium, or RPE. Just one cell thick, the layer lies underneath the retina, the eye's light sensor. The RPE keeps the retina alive and functioning. In diseases like macular degeneration, which affects 10 million Americans, the RPE fails and the retina dies.

Donated eyes

The researchers took RPE cells from donor eyes, from patients ages 22 to 99, and grew them in the lab. Surprisingly, even though the cells don't grow in an adult human, they grew like gangbusters in the lab. When the researchers cultured cells individually, they found that only about 10 percent of the cells actually matured — the others, which were discovered to be stem cells, remained dormant.

They were able to treat these cells with different chemicals to make them turn into fat, brain and other types of cells, proving they were what researchers call "multipotent," meaning they can turn into a variety of different cell types.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We found stem cells within that pigmented layer, that retinal pigmented epithelium, we started testing these cells and found they could divide many times in culture," study researcher Sally Temple, of the Neural Stem Cell Institute at the Regenerative Research Foundation in Albany, N.Y., told LiveScience. "They are a valuable source of new central nervous system cells, and we showed they could differentiate into different cell types as well."

Future therapies

In the future, researchers may be able to harvest these stem cells from a person's eye, culture them in the lab, and then re-inject them to treat a disease. Even better, if the researchers find the particular conditions or chemicals that make the cells grow in the lab, they may be able to figure out how to turn these stem cells on while still in the eye, in order to repair damaged or diseased RPE.

"We have the cells activated in culture, and we can figure out what factors can make them grow and activate them in vivo [in the body], that's one of the things we would love to do," Temple said. "Animals like certain amphibians can regenerate their eye tissues and you feel as if evolutionarily we are now more complex, we should have that ability hidden within us. That's what we are really hopping to release here."

There's still lots of work to do to futher understand these cells and their potential, Astrid Limb, a reseracher from the University College London who wasn't invovled in the study, said. "Although the so called 'RPE stem cells' retain their epithelial phenotype in culture, the authors did not show any evidence that these cells maintain their important metabolic activity," she told LiveScience in an email. "Studies are yet to demonstrate that' RPE stem cells' induced to acquire various phenotypes are capable of function."

The researchers are still working to understand the cells' ability to form different kinds of cell — specifically, what different types of cell they can turn into. "They are a little bit different than the neural stem cells that have been found before, based on the cell types they make," Temple said. "They are a pretty unique type of stem cell."

The study was published today (Jan. 5) in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter @microbelover. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.