8 Human-Like Behaviors of Primates

Our Ape Ancestors

While we lost most of our body hair and bulked up our brains, humans are evolutionarily close to other great apes, with about 97 percent of our genes DNA matching up. Beyond looks, researchers have found a startling number of humanlike behaviors practiced by our ape ancestors.

Say 'No'

Bonobos at the Leipzig Zoo were filmed shaking their heads "no" in disapproval in order to get infants to stop playing with their food (instead of eating it) or to keep an infant from straying. In one instance, a mother retrieved her baby bonobo from an attempt to climb a nearby tree. The infant made continual efforts to scale the tree, with Mom bringing her back each time. The final attempt ended with the mama pulling her infant by the leg and shaking her head while looking at the baby.

While the researchers aren't sure whether the bonobos really mean "no" in their head shakes, the results do hint the behavior may be an early precursor to negative head-shaking gestures in humans, according to study researcher Christel Schneider of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. [Video – Bonobos Make Love – Chimps Make War]

No means "no," for other primates too. "At the Arnhem Zoo, we had a female chimpanzee who would shake her head to say 'no.' For example, when an infant was ready to approach a male in a bad mood, the female would shake her head at the infant," Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University, told LiveScience.

Beg for Food

Other primates are particularly astute at our gestures. "That's why ape communication often looks incredibly human to us," de Waal said. "They beg for food with an open hand (the way human beggars do in the street), have aggressive gestures that look very human, stroke, and touch and hug just like humans, and so the gestural repertoire looks extremely human to us."

A 2007 study of our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, showed the primates were more versatile with hand and foot gestures than with facial expressions. A juvenile chimpanzee in the study showed such hand-waving savvy by combining the reach-out begging gesture with a silent bared teeth face — all in an effort to reclaim food. The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggested humans were communicating with sign language long before speaking.

Another peculiar gesture found in primates: Zookeepers from a British zoo reported some of the mandrills there were covering their eyes with one hand (shown here) to gesture to other monkeys, "do not disturb." In 2011, researcher Mark Laidre of the University of California, Berkeley, said he believes the sign may be evidence of social culture among the animals.

Laugh out Loud

"Perhaps the most humanlike behavior is the laughing by apes when they are being tickled," de Waal told LiveScience. "It is low-pitched compared to human laughter, but the facial expression and the waxing and waning of the laughing sounds are eerily human to the point that those of us familiar with these vocalizations cannot stop ourselves from laughing, too."

Other laughter differences: Humans hoot and holler on exhale, and while chimps can do that, they also laugh with an alternating flow of air, both in and out, researchers say.

In a 2009 study, researchers analyzed and recorded sounds of tickle-induced guffaws from young orangutans, chimpanzees, gorillas and bonobos, comparing these with human infants. They also looked at how the vocalizations fit onto the evolutionary family tree of these primates, finding the best fit matched up with how closely related the species are to one another (based on genetics).

Taken together, the results suggest a common evolutionary origin for tickling-induced laughter in both humans and other great apes, Marina Davila Ross of the University of Portsmouth in the United Kingdom and colleagues write in the journal Current Biology. (Photo shows orangutan Naru being tickled in Borneo in 2005.)

Recognize Faces

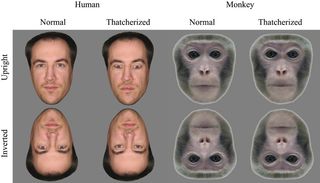

Monkeys can pick a face out of a crowd just as humans can, a study by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen, Germany, found. "From an early age on we are accustomed to the faces of other humans: a long nose, the swing of the lips or the bushy eyebrows. We learn to recognize the small differences which contribute to an individual appearance," said study researcher Christoph Dahl in a statement. Monkeys also can spot the "long noses" in their pals.

Dahl and colleagues revealed the monkeys' ability by using the so-called Thatcherized face, in which different parts are tweaked (for example, the eyes and mouth are rotated 180 degrees. These changes appear strikingly grotesque when viewed right side-up, but hardly noticeable when the whole face is inverted. Our processing abilities let us, and monkeys, spot such changes in facial features, but when inverted, this capability gets lost.

While macaque monkeys noticed the fine face changes in their kin, they paid little attention to the extremely grotesque human faces in both right-side-up and inverted configurations. The same thing happened in humans, who didn't particularly notice the rearranged monkey faces. [Read: Little-Known Disorder: People Can't Recognize Faces]

Eat Junk Food to Calm Nerves

After a romantic breakup or a tough day on the job, we often give in to some sort of gluttony, from a stiff drink to a gallon of sweet ice cream. Turns out, rhesus monkeys do the same when battling stress.

These monkeys naturally form hierarchies, including dominant and subordinate females —the latter of which endures harassment and a general lack of control. The lower-ranked monkeys even show signs of stress, from excessive body-scratching, yawning, self-grooming and pacing, according to Mark Wilson, a neuroscientist at Yerkes National Primate Research Center of Georgia's Emory University. They also eat less than their high-ranking counterparts, possibly due to this stress.

Wilson and his colleagues tested out this stress-comfort-food link by giving both dominant and subordinate females access to banana-flavored pellets of low-fat and high-fat diets, which differed from their standard fare of high-fiber Purina foods.

"When we gave them a diet more like the American diet, high in fat and sugar, what happens is the subordinates eat more," Wilson told LiveScience in 2008 when the study was published. "It's a comfort food. The dominant monkeys don't eat it in excess like the subordinates."

While the high-ranking monkeys only ate during daylight hours, the social subordinates continued to chow down on the fat-laden foods (as well as low-fat ones) day and night, according to the research results published in the journal Physiology and Behavior. (Photo shown here: Baby rhesus macaque monkeys hugging in Kathmandu, Nepal.)

Use Sex Toys

Chimpanzees are the only nonhuman animal species known to make and use a wide range of complex tools, which may include the chimp version of vibrators. In the early 1960s, primatologist Jane Goodall first watched a chimpanzee in Tanzania fashion a blade of grass into a tool to fish termitesfrom a mound. Since then, chimpanzees have continued to reveal their astonishing abilities to create and use advanced tools, including some that were merely for pleasure.

"The tool kits of most chimpanzee populations consist of about 20 types of tools, which are used for various functions in daily life, including subsistence, sociality, sex, and self-maintenance," primatologist William C. McGrew wrote in an essay in the Apr. 30, 2010, issue of the journal Science. [Video – Jane Goodall's Wild Chimpanzees]

Choose Gender-Specific Toys

Speaking of sex and toys, nonhuman primates, like humans, seem to prefer "gender-appropriate" toys. Whether that's the result of genetics or socialization is not clear.

In humans, boys tend to have more rigid gender-specific toy preferences, while girls are more flexible in the playroom, choosing both monster-truck varieties as well as girly dolls, some studies have suggested. Research has shown both early social experiences and innate factors impact the toy selection.

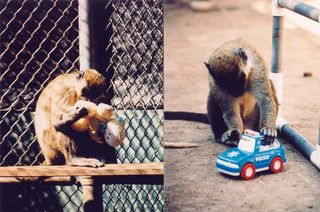

In a 2008 study of 34 rhesus monkeys living with a troop of 135 monkeys, researchers looked at monkey preference for plush toys (the human equivalent of baby dolls) and wheeled objects (such as trucks). Male monkeys showed a consistent and strong preference for the wheeled toys, while females showed greater variability in preferences.

"The similarities to human findings demonstrate that such preferences can develop without explicit gendered socialization," study researcher Janice Hassett of Emory University in Georgia and colleagues wrote in the journal Hormones and Behavior. The researchers go on to say such toy preferences reflect hormonally influenced behaviors and thoughts, which are then sculpted by social processes into sex differences seen in monkeys and humans.

Play Fair

The roots of human fairness likely stretch far back in evolutionary time, evidenced by the many primate species that seem to fuss over inequities. In one study, published in 2007 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers had tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) play a game in which each of a pair of monkeys would hand a small granite rock to a human in exchange for a reward, either a cucumber slice or the more preferable grape. When one monkey handed over the granite stone and landed a grape, while monkey number two got a cucumber, madness ensued.

This recognition of an unfair situation could be critical for maintaining relationships in cooperative societies such as those of capuchins, as well as among humans, the researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna served as editor-in-chief of Live Science. Previously, she was an assistant editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Jeanna has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland, and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.