10 times nature stunned us in 2021

Insect clone armies, secret underwater passageways and cannibalistic toads are just a few examples of nature discoveries that wowed us this year.

Genetic mishaps creating immortal clone armies, whales sharing battle tactics and tardigrades being quantum-entangled — 2021 was a year when the natural world shocked us, horrified us and, some of the time, grossed us out. Here are 10 times nature went wild in 2021.

A bee species created its own immortal clone army

Through a weird genetic fluke, one bee species has created its own army of perfectly identical clones, a June study in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B revealed. In a pinch, the workers of some species of social insects — such as ants, bees and wasps — can reproduce via parthenogenesis, or asexual reproduction. But because this process leads to an unsustainable loss of genetic material, the insects often choose to rear the progeny of their closely related queens as their preferred means of reproduction.

When a genetic mutation enabled the South African Cape honeybee (Apis mellifera capensis) workers to reproduce asexually without losing any genetic material, the proverbial bees' nest was well and truly kicked. Worker bees began embarking upon all kinds of cunning schemes. Some clones inserted their perfect clone daughters into royal chambers so they would be picked as queens, while others took over other hives that housed entitled, layabout offspring. Next on the researchers' agenda is finding out how the gene responsible for this infinite cloning ability can be switched on and off, and at what point the hives parasitized by the clone armies end up collapsing.

Read more: Single bee is making an immortal clone army thanks to a genetic fluke

Rabbits dug up priceless buried treasures on a remote Welsh island

Rabbits occupying a remote island just off the coast of Wales lent their forepaws to an incredible feat of amateur archaeology. The rabbits of Skokholm Island, in Pembrokeshire, unearthed two priceless artifacts: a 9,000-year-old Stone Age tool and a 3,750-year-old pottery piece that was likely from the Bronze Age. Wardens Richard Brown and Giselle Eagle were patrolling the island when they spotted the smooth, oval-shaped Stone Age artifact sitting just outside a rabbit warren. The pottery fragment was found near the same rabbit hole a few days later, hinting that hunter-gatherers had once inhabited the island. The rabbits have not been offered financial compensation for their work, but they have inspired further archaeological investigations on the island — this time, led by humans.

Read more: Rabbits dig up 9,000-year-old artifacts on 'Dream Island'

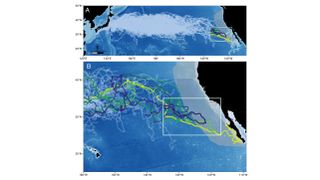

Turtles used a secret underwater corridor to migrate halfway across the world

North Pacific loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) hatch on the shores of Japan and spend large parts of their adult lives sailing the currents of the open Pacific. It's long been a remarkable mystery, then, that they're occasionally spotted 9,000 miles (14,500 kilometers) away in Mexico, especially as the cold-blooded animals would need to pass through life-threateningly chilly waters to get there. A study published in April in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science used GPS tracking tags to crack the case: The turtles surf through a momentary warm opening in the cold water barrier during El Niño, a climate cycle that shifts warm water in the western tropical Pacific Ocean eastward along the equator. The turtles sense the warm corridor and glide right through until they arrive in Mexico. More studies need to be conducted to confirm this hypothesis, but the researchers view it as a fascinating insight that will help protect the majestic, yet highly vulnerable creatures.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Read more: Turtles complete seemingly impossible journey thanks to a hidden 'corridor' through the Pacific

Snakes shove their heads inside living frogs' bodies so they can eat their guts

Scientists in Thailand documented the country's kukri snakes — known for their long, razor-like fangs that they use to slice open eggs — taking their customary frog-eating habits to gruesome new extremes. Researchers spotted both a Taiwanese kukri snake (Oligodon formosanus) and an ocellated kukri snake (Oligodon ocellatus) scarving open live frogs' bellies, wiggling their heads inside and chowing down on the unfortunate amphibians' organs, eating them from the inside out in an excruciating, sometimes hours long, process. Why do the snakes do this? The researchers aren't sure, but it might be to avoid the unpleasant-tasting and toxic parts of the frog prey by going straight for the delicious entrails.

An eel pushed its head out of a living heron's body so that it could escape its guts

The only thing that's comparably as bad as having your guts entered is having them dramatically exited — which is exactly what happened to an unfortunate heron in Delaware this year. Thinking it had safely swallowed an American eel (Anguilla rostrata) whole, the unfortunate bird was no doubt surprised when the eel pulled an "Alien" by erupting violently from the bird's stomach. Photographer Sam Davis snapped a shot of the heron flying, seemingly unperturbed, with the eel dangling out. Davis told Live Science that at first, he thought the eel was biting onto the heron, but a later inspection of his photos revealed the bizarre and grisly reality. How the eel burst out of the heron is unclear. A different type of eel, the snake eel, can emerge from the guts of fish after being swallowed alive, but scientists don't know how many eel species can perform this rare feat or which animals have been unlucky enough to have it happen to them.

Read more: Alien-like photo shows eel dangling out of heron's stomach in midair

A mountain goat took down a grizzly bear with its horns

The discovery of a dead 154-pound (70 kilograms) female grizzly bear (Ursus arctos horribilis) on a popular Canadian hiking trail this year led to its own bizarre murder mystery. In a spectacular twist, an analysis made by park rangers after the bear's carcass had been airlifted away revealed that the ursine victim had in fact been stabbed multiple times in the neck and armpit by the sharp horns of a mountain goat. As bears often hunt by attacking the neck, back and shoulders of their prey, it seems the goat killed its attacker with some well-timed thrusts of its head.

Read more: Mountain goat kills grizzly bear by stabbing it with razor-sharp horn

Whales share evasive tactics to escape harpoons

Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) have excellent social skills and communicate through clicks and body language. In a study published March 17 in the journal Biology Letters, scientists reported that sperm whale communication includes the sharing of battle tactics. By analyzing the newly digitized logbooks of 19th-century whalers, scientists found that the strike rates of the whalers upon their targets decreased by 58% in just a few years.

The whales had learned to eschew their usual tactics of forming defensive circles (as they would for orca attacks) in favor of swimming upwind of the harpooners' wind-powered boats. More remarkable still, whales in regions that hadn't been attacked before had also learned the new tactic by following the lead of those who had.

Read more: Sperm whales outwitted 19th-century whalers by sharing evasive tactics

Cannibalistic cane toads are eating so many of their young that they're speeding up evolution

Australia's invasive cane toads (Rhinella marina) are cannibalizing themselves so much, it's making them evolve faster. They were brought Down Under by farmers in the 1930s to gobble up beetles that were destroying sugarcane fields, but the toads had no natural predators. So the toads' population jumped from an initial 102 to more than 200 million. With skyrocketing populations and limited food,the ever-adaptable toads soon resorted to cannibalism. Just after hatching, cane toad hatchlings exist in a vulnerable state for just a few days, making them ripe pickings for their older tadpole siblings. A study published in the Aug. 31 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences revealed that this cannibalism has even affected the evolution of the invasive cane toads, accelerating their development so they spend one-fifth less of their time in vulnerable their pre-tadpole state than their noninvasive cousins in South America.

Read more: Cannibal toads eat so many of their young, they're speeding up evolution

Sea snakes are mistaking scuba divers for potential mates

Swimming off the Keppel islands in Australia's southern Great Barrier Reef, one diver noticed that he was creating quite a stir among the highly venomous male sea snakes. The underwater reptiles would chase the diver before wrapping themselves around his fins and amorously licking the surrounding water. A study by the diver and a fellow researcher, published Aug. 19 in the journal Scientific Reports, revealed the snakes' unusually frisky behavior was exactly as it appeared: The snakes had mistaken him for a potential mate.

In fact, many of the 158 interactions the diver had with the snakes happened during the snakes' mating season, which falls between May and August. Having only recently evolved to live in the ocean from snakes that once lived on land, the animals have incredibly poor eyesight, which means the sexually frustrated snakes can confirm an unfortunate diver isn't a female snake only by licking them. Worse still, as females typically flee from males during mating, escaping the snakes only further mimics the courtship ritual.

Read more: Sexually frustrated sea snakes mistake scuba divers for potential mates

A tardigrade became the first quantum-entangled animal in history

Tardigrades are, without a doubt, some of the hardiest animals ever to have existed. Name an ordeal, and it's likely the "moss piglets" have already survived it — from being shot out of guns, bathed in boiling-hot water, exposed to intense ultraviolet radiation and crash-landed onto the moon. The microscopic critters have survived many ridiculous scenarios because they can dehydrate themselves into a near-indestructible "tun" state. And if that weren't amazing enough, a study published on the preprint database arXiv in December claims that tardigrades have taken a fresh leap into the quantum realm — by becoming the first observed quantum-entangled animals in history.

After collecting three tardigrades from a roof gutter in Denmark, scientists forced the animals into their frozen "tun" states by cooling them down to within a mere fraction above absolute zero (minus 459.67 degrees Fahrenheit, or minus 273.15 degrees Celsius), the temperature at which atoms stop vibrating. Then, by placing them within an electrical system, the scientists said they brought the animals into a state of temporary quantum entanglement, linking their properties with those of the electrical device. After reanimation, the one tardigrade that survived could have a reasonable claim to being the first animal ever to survive quantum entanglement. This study, which has proved controversial among some physicists, is still awaiting peer review.

Read more: Frozen tardigrade becomes first 'quantum entangled' animal in history, researchers claim

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Most Popular