The world's largest iceberg has just broken in two

The new iceberg is the size of a small city. The main iceberg is the size of a state.

The world's largest iceberg has just broken in two, with a chunk of ice about the size of Queens and the Bronx combined splitting off from the main berg.

The mammoth A-68a berg first split from Antarctica's Larsen C ice shelf in 2017, Live Science previously reported. The giant hunk of ice has been drifting ponderously northward ever since. From the water, A-68a would look a bit like a moving island, with cliffs rising up to 100 feet (30 m) above sea level. As recently as April, it measured 2,000 square miles (5,100 square kilometers), or about as big as three Houstons plus one Chicago (or 1.7 Rhode Islands).

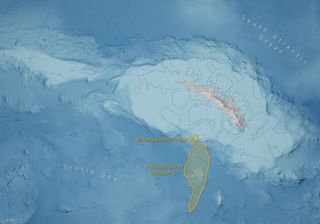

Recently, this floating ice-land has been on a collision course with South Georgia Island, a wildlife refuge in the South Atlantic Ocean that's home to millions of penguins, seals and other wildlife.

It's not clear exactly why the iceberg fractured, but a crash into the shallow seabed several dozen miles from the South Georgia shoreline may have caused the split, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

Related: 10 climate myths busted

The ESA's Copernicus Sentinel-3 mission captured A-68a's drift toward South Georgia in a series of images between Nov. 29 and Dec. 17.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It appears that in recent days the iceberg spun clockwise, moving one of its ends into shallow water, the ESA said. In that region, the seafloor is just 650 feet (200 m) deep, close enough to the surface for the bottom of the iceberg to have scraped against. In the process, the smaller piece — expected to take the name A-68d — likely snapped off.

It remains to be seen where the iceberg will go from here.

Past chunks of ice have traced similar paths north from the southernmost continent past South Georgia. But there is some concern that if A-68a remains offshore for too long, it could block the nearby waters where the penguins that live on the island feed.

"The actual distance [the animals] have to travel to find food (fish and krill) really matters," Geraint Tarling, an ecologist with the British Antarctic Society, said in a statement. "If they have to do a big detour, it means they're not going to get back to their young in time to prevent them starving to death in the interim."

Future images and observations will likely reveal how much of a threat A-68a will end up posing to the waddling birds.

After A-68a's spectacular breakup, another iceberg, farther south in Antarctica's Weddell Sea, is now the world's largest at 1,500 square miles (4,000 square km), according to ESA. Its name is A-23a.

Originally published on Live Science.