Stained-glass 'graphic novel' reveals miracles of Archbishop of Canterbury

You can see it in a new exhibit at the British Museum.

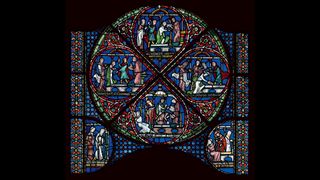

A medieval stained-glass window shows tales of miraculous healing from castration, lameness and blinding, in vivid panels that resemble the lurid pages of a modern graphic novel. For the first time since they were created in the 13th century, those scenes will be on display outside the window's cathedral home.

More than 500 years ago, 12 stained glass "Miracle Windows" were installed at Canterbury Cathedral in the United Kingdom, depicting some of the hundreds of purported miracles performed by Thomas Becket, the 12th-century Archbishop of Canterbury. Seven windows survived to the present, and their panes tell astonishing tales of Becket healing injuries, diseases and birth defects.

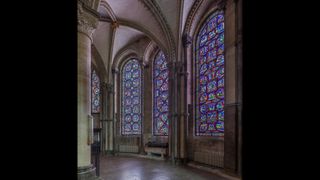

Now, one of these treasures is temporarily leaving the cathedral's Trinity Chapel for a first-ever appearance at the British Museum in London. In the exhibit "Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint," the window will stand alongside other historic objects, manuscripts and art representing Becket's life; his rise to power and estrangement from King Henry II; his condemnation as a traitor and his brutal assassination; and his saintly legacy.

Related: The 10 most controversial miracles

"Contained within the window we're borrowing for the exhibition are multiple individual stories," said Naomi Speakman, curator of Late Medieval Europe for the British Museum. "The entire series of Miracle Windows at Canterbury were made to reflect the incredible miracle stories that were compiled in the three years after Becket's death."

One story shows two sisters — daughters of Godbold of Boxley — who had been lame since birth, said Leonie Seliger, director of Stained Glass Conservation at Canterbury Cathedral. The sisters prayed at Becket's tomb, and, the story goes, only one of them was healed. However, the next panel in the sequence shows the second sister weeping at the unfairness of her fate, whereupon Becket heals her, too, Seliger told Live Science.

Another story shows Hugh of Jervaulx, who experienced a massive nosebleed after he received "the holy water of Thomas Becket" — water mixed with drops of Becket's blood. In medieval medicine, bloodletting was thought to cure some illnesses, and Hugh of Jervaulx apparently recovered completely after his nosebleed, Seliger said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the window's most dramatic miracle story is that of Eilward of Westoning, who was unjustly blinded and castrated for stealing. In a panel featuring his grisly punishment, men hold him down and sever his testicles. But after Becket visits Eilward in a vision, Eilward's missing eyes and genitals grow back. Eilward makes a pilgrimage to Canterbury to give thanks to the saint, and on the way he tells his incredible story to everyone he meets, becoming "very famous," Seliger said. "He allowed people to check that everything had properly regrown," she added.

Two monks were appointed at Canterbury to compile and verify these miracles; they transcribed the details as reported by visitors who said they had been healed by Becket's miraculous presence.

"These were ordinary people," Speakman said. "They're named. They're real people who existed."

Related: 12 bizarre medieval trends

Murder and miracles

Becket was born in London around 1120. As an adult, he quickly rose through the ranks in Henry II's court, becoming Chancellor of England in 1155 and Archbishop of Canterbury in 1162. But tensions sparked between Becket and the king, leading first to Becket's exile in France and then to his murder in Canterbury Cathedral in 1170 by four of Henry's knights, according to the British Museum.

Church bystanders collected Becket's spilled blood, and soon after his death, rumors began to circulate of afflicted people who were miraculously healed through contact with Becket's blood or after they saw him in a dream, Speakman said. Becket was buried in the cathedral, where pilgrims from across Europe visited his tomb. He was canonized by Pope Alexander III in 1173, bringing the cathedral thousands of visitors who were eager for miracles, such as the characters described by Geoffrey Chaucer in "The Canterbury Tales." About 700 miracles were recorded in all, Speakman told Live Science.

According to the monks' records, "Becket does amazing things for them: curing eyesight, curing leprosy, helping those who can't walk, walk again," she said.

Just four years after Becket's death, a fire gutted the eastern part of the cathedral, and 12 magnificent stained glass windows of the saint's miraculous works were commissioned for the rebuilding of the chapel and shrine. Construction of the so-called Miracle Windows began in the 1180s and finished in 1220, with each window measuring nearly 20 feet (6 meters) tall and over 7 feet (2 m) wide. Removing one of them from the cathedral frame was a three-week undertaking requiring a team of conservators, Seliger said.

"I hope that people will see this one window displayed in four sections at eye level, and then want to come to Canterbury Cathedral to see the rest, which are just glorious," Seliger said. But these centuries-old windows aren't just spectacular to look at; they also preserve a rare visual record of just how important Becket was to ordinary medieval people, Speakman added.

"For hundreds of years, pilgrims from all walks of life would have come to Canterbury and gazed at this glass and understood the stories," Speakman said. "I hope it'll give visitors a new appreciation of exactly what Becket meant to all these different people for so long."

"Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint" will be on display at the British Museum from April 22 to Aug. 22, 2021.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.