Earth has a 'pulse' of 27.5 million years

Our planet's geological heart beats at a rhythmic pace.

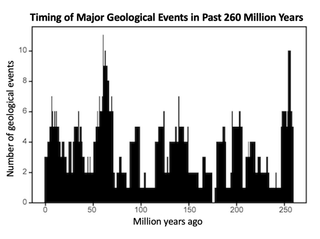

Most major geological events in Earth's recent history have clustered in 27.5-million-year intervals — a pattern that scientists are now calling the "pulse of the Earth," according to a new study.

Over the past 260 million years, dozens of major geological events, from sea level changes to volcanic eruptions, seem to follow this rhythmic pattern.

"For quite a long time, some geologists have wondered whether there's a cycle of around 30 million years in the geologic record," said lead author Michael Rampino, a professor in the departments of biology and environmental studies at New York University. But until recently, poor dating of such events made the phenomenon difficult to study quantitatively.

"Many, but maybe even most, [geologists] would say that geological events are largely random," Rampino told Live Science. In the new study, Rampino and his team conducted a quantitative analysis to see if they were indeed random or if there was an underlying pattern.

Related: Photos: The world's weirdest geological formations

The team first scoured the literature and found 89 major geological events that occurred in the past 260 million years. These included extinctions, ocean anoxic events (times when the oceans were toxic due to oxygen depletion), sea level fluctuations, major volcanic activity called flood-basalt eruptions and changes in the organization of Earth's tectonic plates.

Then, the researchers put the events in chronological order and used a mathematical tool known as Fourier analysis to pick up spikes in the frequency of events. They discovered that most of these events clustered into 10 separate times that were, on average, 27.5 million years apart. That number may not be "exact," but it's a "pretty good estimate" with a 96% confidence interval, meaning it's "unlikely to be a coincidence," Rampino said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers looked only at the past 260 million years — when the dating of such events is most accurate — but they think the results likely extend further back in our planet's history. For example, data from sea level changes go back around 600 million years and also seem to follow this pulse, Rampino said.

It's not clear what's causing such a pulse in geological activity, but it could be internally driven by plate tectonics and movement inside the mantle, the researchers wrote in the study. Or it could have something to do with the movement of Earth in the solar system and the galaxy, Rampino said. For example, the 27.5 million year pulse is close to the 32 million year vertical oscillation around the midplane of the galaxy, according to the study.

One theory is that the solar system sometimes moves through planes containing larger amounts of dark matter in the galaxy, Rampino said. When the planet moves through dark matter, it absorbs it; large amounts of captured dark matter can annihilate and release heat, which can produce a pulse of geological heating and activity, Rampino said. Perhaps this interaction with large amounts of dark matter correlates with the pulse of the Earth, Rampino said. (But of course, this is just a theory. Scientists still don’t know what dark matter is made of, and don’t know how it’s distributed in the solar system.)

Rampino and his team hope to get even better data on the dating of certain geological events and plan to analyze a longer time period to see if the pulse extends further back in time. They also hope that if, one day, they can get better numbers on the astronomical movements of Earth through the solar system and the Milky Way, they can see if there's any correlation in the astronomical and geological cycles.

In any case, if such a pattern exists, the last cluster was about 7 million to 10 million years ago, so the next one would likely come in 15 million to 20 million years, Rampino said.

The findings were published online June 17 in the journal Geoscience Frontiers.

Originally published on Live Science.

Editor's note: This article was corrected to say that the next cluster of events could occur in 15 million to 20 million years, not 10 million to 15 million years.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.