Breaking Up Not So Hard, Study Finds

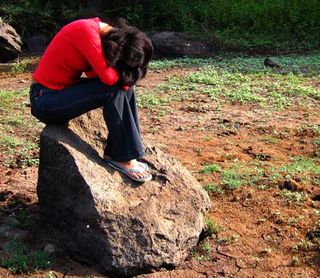

Breaking up is hard to do, but not as hard as we think. New research suggests we overestimate the heart-crushing blow from a romantic split, and some of us make particularly inaccurate forecasts.

"We're not saying breakup is a good time. We're not recommending it," said lead researcher Paul Eastwick, a psychologist at Northwestern University in Illinois. "But it's less bad than people think."

In the moments following the breakup phone call (or text message), life can seem like a cruel joke that will never end. The new study, detailed in the May issue of the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, shows that not only does life snap back to pre-breakup mode twice as fast as one would predict, that initial split is not nearly as crushing as expected. Several heartbreak helpers — unbeknownst to us at the time — apparently kick in to counter the blow.

The results shed light on a general human phenomenon — we are bad at predicting the distress of emotional events, ranging from disappointing election results to lost football games.

Hookups and breakups

For nine months, the researchers monitored nearly 70 freshmen at Northwestern University who had been dating someone for at least two months at the study start.

Every other week, participants completed a quick online survey, indicating levels of distress and happiness, how in love he or she was and whether he or she could imagine being in another relationship. Students also reported when their relationships had ended, if that were the case, and who initiated the split.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If participants still were in a relationship, they answered some forecasting questions: "If your relationship were to end some time within the next two weeks, to what degree will you agree with this statement in two [four, eight, twelve] weeks:"

- "In general, I am pretty happy these days."

- "I am extremely upset my relationship ended."

If participants reported a breakup, they indicated their level of distress and happiness.

Within six months, 26 students reported their romantic relationships had ended. Overall, the participants recovered emotionally in about 10 weeks. While the students did indicate their distress would decline over time, they way overshot the level of initial angst. "It would've taken about double that amount if you'd gone by their predictions," Eastwick said.

Individuals who reported being in love with a partner and those who were on the receiving end of a breakup showed the poorest insight, forecasting an unrealistic level of love-lost sickness.

Faulty forecasts

Several psychological factors could explain these faulty forecasts.

"One explanation is this idea that people are really resilient," Eastwick told LiveScience. "They often don't realize the kinds of psychological defense mechanisms they'll use at the drop of a hat."

For instance, you might focus on the ex's obnoxious habits or other annoying quirks (even ones that may have been cute in the moment).

Often during a breakup, people sort of equip themselves with blinders to anything non-breakup related. "Life goes on in the wake of a breakup," Eastwick said. "And when you're making your predictions, you aren't thinking about all the things that could be positive that might happen in the next week or two."

Another contributor: our stubborn beliefs. "If you have a belief or theory that breakup is 'X' amount bad, it's hard to change that," Eastwick said. "It requires people to really sit down and analyze their own emotions over time. And people typically don't do that kind of thing."

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation.

- Video: Sex and the Senses

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About You

- The Sex Quiz: Myths, Taboos and Bizarre Facts

Jeanna served as editor-in-chief of Live Science. Previously, she was an assistant editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Jeanna has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland, and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Most Popular