Fat Can Build Up in Your Lungs

The findings may explain why obesity is a risk factor for asthma.

Add this to the list of insidious places that fat can accumulate: your lungs.

A new study shows, for the first time, that fat can accumulate in the airway walls of the lungs, the authors wrote. The amount of fat accumulation was higher among people who were overweight or obese, compared with those of normal weight.

What's more, the findings may explain, at least in part, why obesity is a risk factor for asthma, according to the study, published Thursday (Oct. 17) in the European Respiratory Journal.

The link between obesity and asthma has been known for years, but the reason for the link is not completely understood. Some researchers have suggested that excess weight places direct pressure on the lungs, making breathing more difficult. Others have suggested that obesity may increase inflammation throughout the body, which contributes to asthma.

But the new study "suggests that another mechanism is also at play," study co-author Peter Noble, an associate professor at the University of Western Australia in Perth, said in a statement. Fat accumulation may change the structure of people's airways in a way that raises asthma risk, the authors said.

Still, more research is needed to confirm whether fatty tissue in airways really does contribute to asthma, and whether weight loss could reduce asthma risk.

Related: Gasp! 11 Surprising Facts About the Respiratory System

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hidden fat

The researchers had been studying changes in the airways tied to respiratory diseases when they noticed that their lung samples showed that fatty tissue built up in the walls of the airways within the lungs, said study lead author John Elliot, a senior research officer at Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital in Perth. The scientists wondered whether this fat accumulation was tied to body weight.

To figure that out, Noble, Elliot and their colleagues analyzed postmortem samples of airway tissue from 52 people, including 16 who had died of asthma-related causes, 21 people who had asthma but had died of other causes, and 15 people who had no history of asthma prior to their deaths.

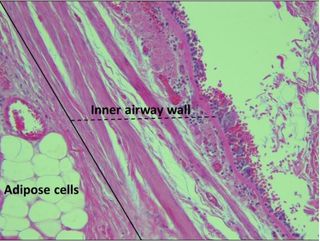

When the researchers used special dyes to analyze the tissue samples under a microscope, they saw fatty tissue that had accumulated in the airway walls among people in each of the three groups.

In addition, the amount of fat in the airway walls was linked with each person's body mass index (BMI), meaning that more fat accumulated in individuals with higher BMIs, compared with those with lower BMIs.

The researchers propose that fat accumulation may lead to a thickening in the airways, which limits airflow. "That could at least partly explain an increase in asthma symptoms," among people with obesity, Noble said.

"This is an important finding on the relationship between body weight and respiratory disease because it shows how being overweight or obese might be making symptoms worse for people with asthma," Thierry Troosters, president of the European Respiratory Society, who was not involved with study, said in a staetment. "This goes beyond the simple observation that patients with obesity need to breathe more with activity … the observation points at true airway changes that are associated with obesity."

Although the findings still need to be confirmed, doctors should support asthma patients to help them achieve or maintain a healthy weight, he said.

- 11 Surprising Things That Can Make Us Gain Weight

- 13 Kitchen Changes that Can Help You Lose Weight

- 7 Tips for Moving Toward a More Plant-Based Diet

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.