Archaeologist Studies Ancient Food for Thought

This ScienceLives article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

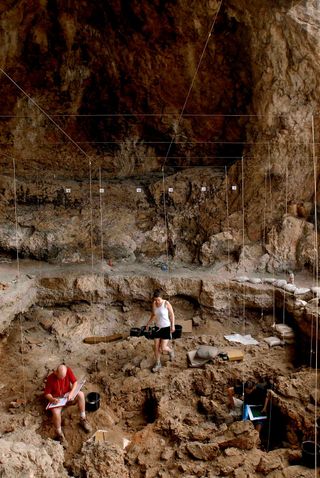

Natalie Munro is a zooarchaeologist, that is, an archaeologist who studies the remains of animals collected by humans in the archaeological record. Her data includes animal skeletal remains (bones and teeth) that most often represent the garbage of past human meals. She uses ecological models to study the interactions between humans and animals in the past. In particular she investigates human hunting strategies, human impacts on past animal populations and animals in human burial contexts. The core of her research program investigates humanity’s transition to agriculture (ca. 12,000-8,000 years ago). In particular, she seeks to understand the conditions that existed at the very beginning of the transition to agriculture to understand the triggers for this important process. Her most important recent research projects include: documenting changes in human dietary breadth across the transition to agriculture as a measure of human population size, resource stress and site-use intensity and investigating human ritual practice at a burial cave in Israel. The excavation of this cave (Hilazon Tachtit) was directed by Leore Grosman of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem. The animals buried in two structures at the site revealed the earliest evidence for: a shaman—an individual perceived to have special ritual, spiritual and or healing abilities—and ritual feasting, meaning communal meals held in association with burial events (including that of the shaman) in the cave. Both shamans and feasts likely existed prior to this time, but could not be detected in the archaeological record. Their detection at Hilazon Tachtit which dates to the very beginning of the transition to agriculture likely relates to important changes in human social and economic practices in response to the settling down of humans into more or less permanent villages and experimentation with cultivation and animal management.

Name: Natalie D. Munro Age: 40 Institution: University of Connecticut Field of Study: Archaeology (Department of Anthropology)

What inspired you to choose this field of study? I was inspired by a combination of interests. Initially these included a curiosity about old objects that had value to their originalowners, a love for the natural world inspired by my parents—in particular my dad who worked for the Canadian Park Service—and a love for the outdoors and the field. Ultimately, I was more inspired to combine the ecological models that I was introduced to during my first degree with my interest in the interactions between human population growth and food supply.

What is the best piece of advice you ever received? A colleague once told me not to get so engrossed in my research that I would lose track of other important things in life. As the mother of two young children, striving for a healthy life balance has taken on an entirely new meaning. Spending time at work makes me appreciate time with my kids all the more and vice versa.

What was your first scientific experiment as a child? My most memorable scientific experiment occurred by accident. While waiting my turn to climb the slide in second grade at the peak of the Canadian winter, I stuck out my tongue and touched it to the ladder’s metal railing. My tongue stuck a little and I observed an interesting residue on the railing. I hypothesized that the residue on the slide had caused by tongue to stick and tested the hypothesis by licking the railing again. This time enough skin was torn off my tongue to abruptly end the experiment and require a trip to the school nurse. I concluded that my hypothesis had been disproven and revised it to state that the water on the tongue will freeze to a metal railing when the temperature drops below freezing. I did not repeat the experiment.

What is your favorite thing about being a researcher? I love the flexibility and diversity of activities that a research career offers. During the academic year I am at the university teaching, writing and analyzing data and during the summer I travel to the field to excavate or collect data from archaeological materials. The regular change of venue and research activities and the excitement of discovery both in the lab and in the field keeps me fresh and motivated.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What is the most important characteristic a researcher must demonstrate in order to be an effective researcher? I believe that rather than one single characteristic, success depends on a suite of characteristics. Even the brightest researcher won’t be successful if he can’t meet deadlines on time. A successful researcher must not only be thoughtful, but also motivated, curious and creative.

What are the societal benefits of your research? Anthropology benefits society by documenting variability in the human condition and teaching cultural relativism—that cultures must be understood in their own terms. An objective of archaeologists is to provide time depth to our knowledge of human diversity. My research contributes to this important goal by documenting human hunting adaptations and ritual practices in the past. My work on human impacts on past animal populations also provides historical depth for understanding the devastation that modern society is currently wreaking on our natural world.

Who has had the most influence on your thinking as a researcher? My thinking has been most influenced by my Ph.D. advisor, Mary Stiner from the University of Arizona. Stiner taught me to see the larger evolutionary context of human adaptation, to ground robust methods and data into a well developed theoretical framework and to balance a research career with other interests. From the beginning of my undergraduate education, I have been very lucky to have had a series of strong female mentors including Stiner, Patricia Crown, Sally McBrearty and Melinda Zeder.

What about your field or being a researcher do you think would surprise people the most? In some ways, archaeology lives up to the romanticism that surrounds it. I get to visit exotic locations and live for months in the field, sometimes with only basic amenities. Nevertheless, the majority of archaeological research consists of painstaking data collection and analysis. Each story that I tell, is backed by countless hours spent recording information on the thousands of tiny bone fragments that make up the garbage of past human dinners.

If you could only rescue one thing from your burning office or lab, what would it be? I wish that it was something more interesting, but this would have to be my trusty laptop computer, which despite missing several keys and functions continues to steadfastly hold all of my precious data.

What music do you play most often in your lab or car? Much of what I listen to falls into the genre of indie/folk-rock. The CDs that are currently getting the most play in my car are the latest discs by Sufjan Stevens (Age of Adz) and Arcade Fire (Suburbs).

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. See the ScienceLives archive.

Most Popular