1st of their kind baby tyrannosaur fossils unearthed

Even as babies, tyrannosaurs had a "distinct chin."

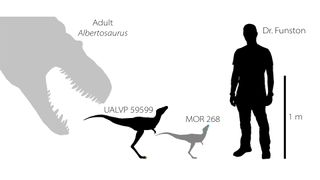

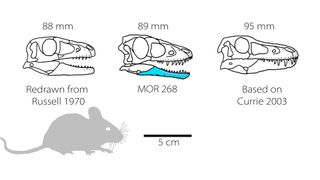

A fossil of what may be a tyrannosaur embryo shows that the gigantic apex predator started out with a skull the size of a mouse.

That conclusion came after the study authors found a toe claw from a baby tyrannosaur in Alberta, Canada in 2017 — which prompted them to analyze a previously known baby tyrannosaur jawbone, found in Montana in 1983. Because the jawbone was too delicate to be removed from the surrounding rock, it had never been properly studied. But now, an analysis of both fossils is revealing all kinds of secrets about these baby beasts.

"These are incredibly rare finds — the first of their kind in the world," lead researcher Gregory Funston, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, told Live Science in an email. "Juvenile tyrannosaurs of any kind are exceedingly rare, and we've never found any bones that we suspected might be embryos, until now."

Related: Gory guts: Photos of a T. rex autopsy

The research, which is not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal, was presented online Tuesday (Oct. 13) at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's annual conference, which is virtual this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

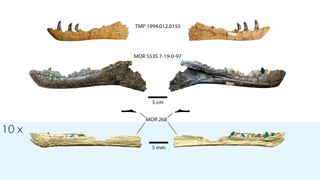

The teensy, 1.1-inch-long (2.9 centimeters) tyrannosaur jawbone still sports eight little teeth. Because it was stuck in the surrounding rock, the researchers scanned the jawbone with a particle accelerator, which let them image the fossil without excavating it. Despite the jawbone's miniature size, "it looks surprisingly like other juvenile tyrannosaurid jaws," Funston said. "It has a deep groove on the inside and a distinct chin, which are both features that distinguish tyrannosaurs from other meat-eating dinosaurs."

These features helped convince other paleontologists that the jawbone truly is from a tyrannosaur — "we can know that these features can be used to identify tyrannosaurs no matter how immature they are," Christopher Griffin, a postdoctoral associate in the Department of Earth & Planetary Sciences at Yale University, who wasn't involved with the research but attended the presentation at the conference, told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The teeth on the jawbone aren't fully developed, and one tooth in particular offers clues that this fossil might belong to an embryonic tyrannosaur, meaning the tiny tyrannosaur would have died before it had hatched.

"In one of the tooth sockets, a replacement tooth is being developed, but in an unusual way: Typically, replacement teeth lie directly below the older tooth, and they eat away at the root to release the older tooth," Funston said. "In our case, the replacement tooth is beside the older tooth, and there's no evidence of root disintegration. This style of replacement has recently been found in the first generation of teeth in reptile embryos."

(The toe-claw fossil might also be from an embryo because one surface wasn't fully formed, Funston noted.)

Embryonic mysteries

It's a mystery which genus of tyrannosaur these fossils are from, but a few well-known predators from this group include Tyrannosaurus rex, Gorgosaurus and Albertosaurus. But even without knowing the genus, "finding the remains of extremely young tyrannosaurs is very exciting," said Kat Schroeder, a doctoral student of biology at the University of New Mexico, who wasn't involved with the research but attended the conference presentation. Embryonic fossils are rare, she told Live Science in an email, because "even before they were born, dinosaurs would have been under threat of predation from egg-stealing mammals, and had this baby tyrannosaur hatched, it likely would have had to avoid being eaten by dromaeosaurs (Velociraptor-like dinosaurs), older tyrannosaurs, crocodilians and possibly even giant pterosaurs."

Related: Photos: Fossilized dino embryo is new oviraptorosaur species

More is known about tyrannosaurs older than 2 years — for instance, for a study published in June in the journal PeerJ, a paleontologist exhaustively analyzed T. rex's growth from tiny tot to hulking adult. Other tyrannosaurs also have extreme growth patterns, "hatching out not much heavier than a house cat, and growing to the size of an elephant over 15 years or so," Schroeder said.

Funston noted that researchers have yet to find any tyrannosaur eggshells, so perhaps these dinosaur kings laid soft-shelled eggs, which don't fossilize well. This wouldn't be without precedent: Earlier this year, two studies published in the journal Nature offered evidence that the Triceratops-like dinosaur Protoceratops and the long-necked sauropodomorph Mussaurus likely laid soft-shelled eggs, as did the marine reptile Mosasaurus.

"We don't have any direct evidence of these soft-shelled eggs yet, but these clues tell us we should start looking," Funston said.

Editor's note: After its presentation at the October 2020 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology conference, this research was published online Jan. 25, 2021 in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.