Astronomers Uncover 39 Ancient Galaxies — Moving So Fast That Even Hubble Can't See Them

These galaxies could rewrite our history of the early universe.

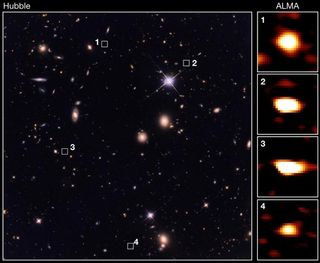

Ancient, massive galaxies haunting the dusty reaches of our universe have been in hiding, invisible to the eyes of the famous Hubble Space Telescope. But now, astronomers sifting through infrared data have discovered 39 of them — lurking in strange places from the early universe where (and when) the night sky would look very different from our own.

If you were to approach one of these long-ago galaxies while inside a spacecraft, it would probably be at least recognizable to you: stars you could see with the naked eye, swirling dust, a big black hole at the center. And if you were to somehow appear there today, it would likely look quite different than it did more than 11 billion years ago, in the early history of our universe. But the light reaching Earth in 2019 from these massive, distant galaxies had to travel so far that it's billions of years old, showing us what that part of the universe looked like in its first 2 billion years of existence. And the light is so altered that the Hubble — built to see in ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared light — couldn't see it at all.

That's because these faraway galaxies, like most faraway things in our universe, are speeding away from us — a consequence of dark energy driving the expansion of space. As Live Science has previously reported, light from objects speeding away from us gets stretched into longer, redder wavelengths. And these superdistant galaxies are speeding away so fast, according to the researchers who discovered them, that the ultraviolet and visible light they emitted has shifted entirely into the long "submillimeter" wavelength range that even Hubble can’t detect. [15 Unforgettable Images of Stars]

As a result, the researchers wrote in a paper published Aug. 7 in the journal Nature, most astronomers who are focused on the first 2 billion years of the universe have ended up studying oddballs: galaxies very far away that nonetheless are motionless enough relative to Earth that Hubble can see them. But these nonredshifted galaxies probably aren't the norm.

"This raises the questions of the true abundance of massive galaxies and the star-formation-rate density in the early Universe," the researchers wrote. In other words, how many galaxies were really around back then, and how fast were they making stars?

Astronomers have in the past spotted individual massive galaxies from the deep past, the researchers wrote, as well as smaller galaxies that tend to be shrouded in dust. But for this work, the team used a series of submillimeter-sensitive telescopes to spot these 39 previously unseen ancient galaxies.

"It was tough to convince our peers these galaxies were as old as we suspected them to be. Our initial suspicions about their existence came from the Spitzer Space Telescope's infrared data," Tao Wang, lead author of the paper and astronomer at the University of Tokyo, said in a statement. "But [the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile] has sharp eyes and revealed details at submillimeter wavelengths, the best wavelength to peer through dust present in the early universe. Even so, it took further data from the imaginatively named Very Large Telescope in Chile to really prove we were seeing ancient massive galaxies where none had been seen before."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

And those findings are significant for early universe models and for explaining how our modern universe came to exist.

"Such a high abundance of massive and dusty galaxies in the early Universe challenges our understanding of massive-galaxy formation," the researchers wrote in the paper. [9 Most Intriguing Earth-Like Planets]

Several different existing models predict a much lower density of these sorts of galaxies, even though researchers have long suspected some would be out there. With this new discovery, scientists have to go back and refine their models to account for this new data set of previously unseen things.

These galaxies, the researchers wrote, are likely part of the group that gave rise to modern massive galaxies. But they had much more dust and were far denser than the Milky Way galaxy.

"The night sky would appear far more majestic. The greater density of stars means there would be many more stars close by appearing larger and brighter," Wang said in the statement. "But conversely, the large amount of dust means farther-away stars would be far less visible, so the background to these bright close stars might be a vast dark void."

- Interstellar Space Travel: 7 Futuristic Spacecraft to Explore the Cosmos

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- The Best Space Photos Ever: Astronauts & Scientists Weigh In

Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular