Shark or Elephant Fish? Limb Growth Gene Helps Decide

You have a lot more in common with elephant fish than you probably think. Granted, you likely don't live hundreds of feet below the ocean's surface, emerging to shallow water once a year to lay your eggs at the bottom of a murky bay. And your skeleton is probably made of bone, not cartilage.

But it turns out that the same gene that controls the development of your fingers, toes, legs and arms also controls the growth of certain appendages in elephant fish and their shark cousins.

A new study finds that the gene, whimsically named "sonic hedgehog," is responsible in part for whether an embryo turns into a shark or its relative, a floppy-nosed elephant fish. (Much like sharks, elephant fish are cartilaginous, meaning they lack hard bones.)

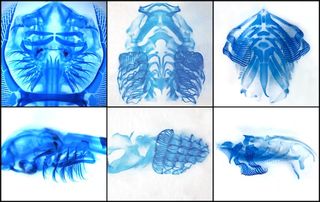

The study took researchers quite literally to new depths: They had to scuba-dive in dark, shark-infested waters for elephant fish eggs to use in the study. [Image: Elephant Fish Embryo]

"It definitely was really creepy," study researcher Andrew Gillis, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge, told LiveScience.

But it was worth it: "This highlights one way that evolution can sort of tinker with something in the egg that can have a pretty substantial anatomical consequence in the adult," Gillis said.

Sonic hedgehog and elephant fish

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elephant fish can grow to be about 4 feet (1.2 meters) in length. Unlike sharks, which have multiple rows of razor-sharp teeth, the elephant fish has one big plate-like tooth, a structure better suited for crunching up the invertebrate animals it eats off the ocean floor.

Gillis and his colleagues had previously shown that they could manipulate the genes of a shark embryo in the lab to change the length of little rods of cartilage called brachial rays, which prop up the fleshy flaps over the gills of sharks, skates and other non-bony fish. Sharks have five sets of gill flaps with brachial rays, while elephant fish have just one. That made elephant fish the perfect natural test case to find out whether evolution uses the sonic hedgehog gene to make the same changes in nature that Gillis made in the lab.

So the team hopped in the water in Western Port Bay in southeastern Australia, amidst jokes from local fishermen about the size of sharks they'd caught in the water.

"They would reassure us that we probably wouldn't even see it coming anyway," Gillis said of a potential shark attack. "Because the visibility was so bad."

Thanks to that bad visibility, the researchers didn’t so much look for elephant fish eggs as they did grope for them, Gillis said. Another expedition to New Zealand yielded additional specimens.

Back in the lab, the researchers let the embryos develop alongside embryos of dogfish sharks. Using a technique that reveals the expression of a gene, the researchers found that the sonic hedgehog gene matched up with the growth of brachial rays. Early on, sonic hedgehog was active in five rows in both species. But the gene switched off early in four of the rows in elephant fish, halting the development of those brachial rays.

"In the back rows, where [the gene] turned off early, all that formed were these little tiny nubbins of cartilage," Gillis said. [Image: Head anatomy of a skate, shark and elephant fish]

Ancient tool kit

The research is a bit like genetic archaeology, according to Neil Shubin, a University of Chicago professor of organismal biology and anatomy, and one of the other authors of the paper (published Jan. 10 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

"The more we look, the more we find that the tool kit — the recipe, the genes, particularly the regulatory genes that build bodies — that these are really, really ancient things," Shubin told LiveScience. By investigating the origin of these genes, he said, we can better understand what the common ancestor of both humans and elephant fish looked like.

"Not only are we seeing the history of how organs are built, but we're seeing the history of the tool kit," Shubin said.

The next step is to manipulate sonic hedgehog in the lab to prove the association between gene activity and brachial ray growth, Gillis said. The research has one somewhat surprising side effect, he added: No one has ever dived for elephant fish eggs before, and the information Gillis and his team have gathered is helping fisheries' officials manage the species.

"They're very abundant," Gillis said of the fish. "And we'd like to make sure it stays that way."

- Jaws of Death: 10 Reasons Why Great White Sharks Are Great

- Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures

- Image Gallery: Freaky Fish

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular