How Corals Could Survive Climate Change

The ability of Caribbean corals to withstand the threat of warmer oceans may depend on where the corals' parents grew up, a new study suggests.

A species of coral born in Mexico may be able to survive the warming ocean waters caused by climate change better than the same coral species living in Florida, researchers found. This ability to withstand warmer waters comes from the genes passed down to young corals in reefs from different areas of the Caribbean.

Rising water temperatures and acidic oceans from climate change threaten coral reefs around the world. The new research may lead to a genetic screen for coral that will help researchers predict those species most at risk from climate change — similar to genetic screens for women at risk for breast cancer — said study co-author and biologist Iliana Baums of Penn State University.

Same species, different spots

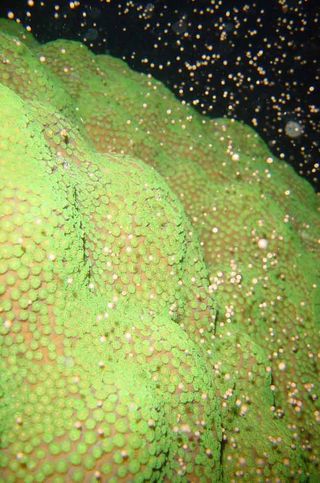

Mountainous star coral (Montastraea faveolata) is the most abundant reef-building species in the Caribbean. Despite its abundance, the coral is listed as endangered by the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), which highlights species facing extinction. Some areas of the Caribbean have lost 90 percent of their mountainous star coral population.

To study how well the corals faired in warmer waters, researchers turned not to existing reefs, but to coral larvae.

"We decided to focus on coral larvae because the successful dispersal and settlement of larvae is key to the survival of reefs," Baums said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Studying adult coral is difficult because they have a symbiotic relationship with algae. Free-swimming coral larvae are algae-free, so when they respond to high heat, scientists know that the response is only from the coral, and not from the algae. These larvae are more than just useful test subjects; they are also more vulnerable to climate change than adult coral.

Scuba diving scientists set nets over coral in Key Largo, Fla., and Puerto Morales, Mexico to intercept blasts of eggs and sperm during the annual mass spawning that happens a few days after the full moon in August. Without the nets, fertilized larvae would rocket to the surface and then float back down over two weeks before settling on the hard surfaces where they spend the rest of their lives.

After spawning, the scientists race back to the shore — they only have an hour to make the trip — to put the eggs and sperm in aquarium tanks before they die, or else the researchers have to wait until next year for another mass spawning.

Scientists raised the coral larvae from Florida and Mexico in their average native water temperatures and also in slightly warmer water (88.7 degrees Fahrenheit (31.5 Celsius) for the coral from Mexico and 86 F (30 C) for the coral from Florida).

Genetic differences

Half of the Florida larvae raised in the warmer water were deformed compared to the normal-temperature embryos, none of which were malformed. The Mexican coral larvae showed the same pattern but they were less strongly affected by the elevated temperature.

Although both populations represent the same species, their different responses to heat stress shows that even within a single species, there are distinct genetic differences that may give one population an advantage over the other, Baums said.

The researchers looked at the DNA from the two coral populations and pinpointed the key genetic differences between the coral from Mexico and Florida that allowed the former to fare better in warmer waters. The scientists' next goal is to use this information to develop a genetic screen to predict those species of coral that have a better chance of surviving in warmer oceans.

The study is detailed in the June 23 edition of the online open-access journal PLoS One.

This article was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.

- Images: Incredible Coral

- Worlds Apart: A Cautionary Tale of Two Coral Atolls

- The World's Biggest Oceans and Seas

Most Popular